Darwin’s Champions

Darwin’s Campaigners continued

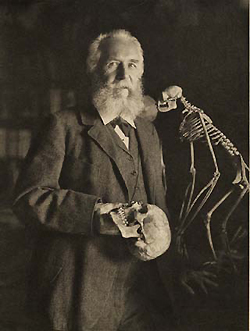

Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), 1904

The flamboyant German zoologist, physician, artist, and philosopher, Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), wrote widely-read, illustrated books that claimed the mantle of Darwinism. Like Huxley, Haeckel promoted Darwinian science as an all-encompassing philosophy, part of a program of educational and social reform conducted through books and popular lectures. Also like Huxley, he was a skilled comparative anatomist, first working in invertebrate zoology on radiolarians—microscopic animals. As a young professor of anatomy at the University of Jena, he visited Darwin in England in 1866, and became a disciple. In 1868, Haeckel published Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte, a beautifully illustrated work, translated as The History of Creation. Haeckel’s images were as important to his argument as his words. In Anthropogenie, a book on the evolution of the human species published in 1874, Haeckel presented his famous drawings of vertebrate embryos.

Protomyxa, in Ernst Haeckel, The history of creation, 1876

These linked to his best known axiom, “Ontology recapitulates phylogeny.” That is, as it develops, each embryo moves through the changes that characterized its species’ evolution: an individual’s embryological development—its “ontology”—recapitulates the species’ evolutionary path—its “phylogeny.” The best of Haeckel’s drawings and sketches were brought together as Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature, 1904), laying out the beauty and order that he found in a self-generating world. In distinction to Darwin, though, Haeckel saw direction in evolution, with life progressing inexorably from simple to complex, from radiolarians to humans, and—in thrall to the prejudices of his time—to Europeans as the pinnacle of the process. He predicted the discovery of a “missing link” in the chain between humans and apes, apparently confirmed in 1891 with the discovery of fossils of Java Man in Indonesia. Far more strongly and far more speculatively than Darwin, Haeckel set out natural science as the basis for a new world view, to great success.

Last Reviewed: May 8, 2014