The Books of Darwin

More Books continued

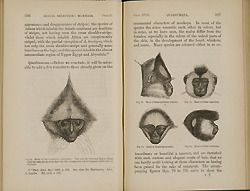

Different coloring in monkeys, in Charles Darwin, The descent of man, 1871

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871)

In another facet of the “big species book,” Darwin published on two separate but related topics: human evolution and sexual selection. At this point, some twelve years after the publication of the Origin, the Darwinian debates had already taken a public turn around “human exceptionalism”: that is, were there distinctly human traits that evolution did not bear on, that, in fact could be taken as signs of divine providence or human uniqueness? Darwin felt constrained to address this topic.

Darwin’s evidence for human evolution was founded in anatomy and embryology of the great apes. But in this he was not the first, nor even the most daring of his time. He made two new points, though. First, Darwin stressed the continuity, and not the disjuncture, of the mental and emotional life between animals and humans, and—as T. H. Huxley (1825-1895) later did as well—saw the origins of the moral life in the sociability and compassion that were evolved human traits. Second, he saw the evolution of the human races as the result of sexual selection. Sexual selection was one answer to the problem of difficult cases such as the peacock. The seeming disadvantage of bright, heavy feathers in the male peacock was hard to explain: what adaptive advantage did they provide? Darwin maintained that they gave the same advantage that possessed by any well-dressed, self-confident man—they attracted the opposite sex! And so Darwin took on one of the most vexed issues in the late-nineteenth-century Western world, the origin of the human races. Sexual selection worked through appearances, and so it explained many observable distinctions among the races, which, Darwin maintained, were distinctions of appearance only—hair color and texture, skin color, and facial features. Sexual selection, he asserted, had led to the different human races through human aesthetic choices. Taste was a random quality, no different from any other variation—some people, for no particular reason, preferred one appearance over another. Through sexual selection, and over time, these tastes became fixed in different races. In The Descent of Man, Darwin continued to blur and blend the seemingly strict categories of the natural order.

Last Reviewed: May 7, 2014