Cases

Michael Blassie unknown no more

We want the truth, we want to bring him home.

—Jean Blassie, mother of 1st Lt. Michael Blassie, 1998

It may be that forensic science has reached the point where there will be no other unknowns in any war.

—William S. Cohen, U.S. Secretary of Defense, 1998

On Memorial Day 1984, the remains of a soldier killed during the Vietnam War were laid to rest in the Tomb of the Unknown at Arlington National Cemetery. A decade later, however, questions began to arise about the identity of this unknown soldier.

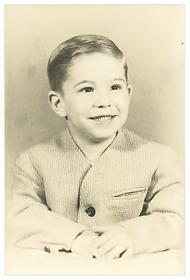

First Lieutenant Michael Joseph Blassie, 24, was shot down over South Vietnam in 1972 and presumed dead. When family members received word that his remains might be buried in the Tomb of the Unknown, they petitioned the Department of Defense to open the site and conduct previously unavailable DNA testing. In 1998 the Tomb of the Unknown was opened and the remains of the Vietnam Unknown—identified as X-26—were removed.

Forensic anthropologists took the aged and damaged samples of bone for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) testing. Because mtDNA is passed along the maternal line, scientists compared the Unknown Soldier's DNA against two samples submitted by First Lieutenant Blassie's mother and sister and found a match.

On July 11, 1998, 1st Lt. Michael Blassie was buried with full military honors in Jefferson National Cemetery, Missouri, near his hometown, in the same cemetery as his father.

Going further: Lt. Blassie and the unknown soldier

Michael Joseph Blassie, the oldest of five children of a St. Louis meat cutter, entered the Air Force Academy in 1966 and received his officer's commission in June 1970. During a tour of Vietnam, he served as a member of the 8th Special Operations Squadron. On May 11, 1972, at age 24, his A-37B Dragonfly aircraft was shot down near An Loc, about 60 miles north of Saigon.

Immediate recovery attempts were launched, but Blassie had crashed in an area controlled by enemy forces so it was impossible to examine the crash site. Five months later, during a sweep of the area, a South Vietnamese Army patrol recovered a pelvis, an upper arm bone, and some ribs, as well as the remnants of a flight suit, a life raft, pieces of a parachute, and part of a USAF holster. The remains and associated materials were eventually turned over to the U.S. Army Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii for analysis and identification. They were initially classified as belonging to Lt. Blassie. However, analysis at the time suggested that the remains were not a compelling match to Blassie's age and height. With the conflicting information between the forensic analysis and the physical evidence, the remains were designated as "Unknown" and assigned the number "X-26."

The timely and accurate identification of men and women who die while serving in the armed forces has long been a priority for the United States government. The Armed Forces have adopted the latest advances in fingerprint and dental identification, and forensic anthropology and radiology. But not all remains can be identified with such methods. Records can get damaged or destroyed, and post-mortem materials can be affected by decomposition, body fragmentation and exposure to heat.

With the invention of the polymerase chain reaction in 1985, DNA analysis moved to the forefront of forensic technologies. In 1991 the Department of Defense founded the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL). AFDIL has used DNA analysis to identify the remains of at least 150 military personnel from Vietnam, Korea, and World War 2, and assisted in the identification of victims from high profile disasters, both natural and man-made. Now that DNA samples are taken from everyone who joins the U.S. Armed Forces, there may never be another American "unknown soldier."

Mitochondrial DNA testing

Human beings have copies of DNA from each biological parent, stored in the nucleus of every cell. DNA is also stored in tiny, energy-producing structures in the cells, called mitochondria. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) differs from nuclear DNA because human beings inherit mtDNA solely from the mother and share this information with siblings and maternal relatives. Unlike nuclear DNA, each cell carries more than a hundred copies of mtDNA, since each cell contains many mitochondria but only one nucleus. The ability to match mtDNA between related individuals, and the fact that it does not degrade as rapidly as nuclear DNA, makes it a valuable tool in the identification of human remains.