It probably happened in November 1871. U.S. Army Surgeon general Joseph K. Barnes mentions, in a letter a year later, that about that time 'it was decided' to radically re-envision his office's library as a national medical library, one that would be accessible to the public and serve as a medical version of the Library of Congress. Though begun barely a decade earlier, the Army Medical Museum was already ambitiously striving to be the world's greatest medical museum. It seemed natural that its library should grow in equal proportion.

Already the Library had significant holdings. Its 10,000 to 13,000 volumes numbered more than in any other medical repository in the United States except those of the venerable Pennsylvania Hospital and the College of Physicians and Surgeons, both in Philadelphia.

Its collection policy, however, had been limited. It was to serve the administrative needs of the Surgeon General and his staff. During the Civil War, after decades of maintaining standard reference works, general medical texts, and a few journals used by medical military staff, the office had developed an added purpose. The incipient medical museum and the plan to produce a comprehensive medical and surgical history of the Civil War required acquisition of more specialized medical knowledge. After the war, the library also began concentrating on studies of yellow fever and cholera, which were regular scourges of army personnel in scattered outposts.

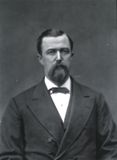

As the library grew large enough to need regular attention and organization, Surgeon General Barnes delegated responsibility to one of his staff. John Shaw Billings, U.S. Army Assistant Surgeon, had been assigned to the Surgeon General's Office in January 1865. In the fall of that year, Barnes added the Library's welfare to his list of duties. The newly-conceived position slowly coalesced into more definite form. During 1867 Billings was given sole responsibility for purchasing publications, and he also began acquiring titles that would serve more than just current military medical inquiries, such as incunabula.

Billings' predilection for the library portion of his duties was evident to Barnes and surely encouraged him to believe he had the right man to go forward with the Library's expansion.

By the end of 1871 the Library's new future had been decided, and Billings was poised to fulfill the promise. He summarized his intentions in a letter to a potential donor in 1872:

I am trying to form a great national Medical Library here -- a work of great labor -- which I am satisfied can only be done under government auspices. We have now about 18,000 vols -- on our shelves in the fireproof building of the Army Med Museum. Catalogued and open to the profession -- and it is now on a proper basis as the Medical Section of the National or Congressional Library. I want to make it as complete as it can be made and the great difficulty of course is to get old pamphlets -- and to complete our files of journals.

From January through December of 1872, the first full year of the national medical library, Billings initiated an intense, determined, almost frenzied assault on book dealers, libraries, writers, publishers, and private collectors to stock a universe of medical knowledge. But this great undertaking was limited by federal funding. The $7000 appropriated for both the museum and Library in fiscal year 1872 was inadequate to purchase all newly published medical works and to subscribe to all medical journals. Billings would have to rely on his will and his wiles to find the ways to acquire his universe.

This exhibition presents notes and anecdotes of Billings' experiences during that first all-encompassing year, as well as traces of the Library's origins that are still found in the stacks.

Receipt for a subscription to Dental Cosmos. This form shows both ways that Billings filled the collection with journals -- by acquiring back issues and by subscribing for all future issues.

Report on Epidemic Cholera and Yellow Fever in the Army of the United States, during the year 1867, 1868. The Library collected more works on yellow fever and cholera after the war to support efforts to fight the diseases at army installations.

Items from the Surgeon General's Library

Last Reviewed: February 8, 2024