Slavery put in place social and culinary boundaries that could separate those who ate from those who worked.

The preparation of food is often described as a labor of love, capable of strengthening family ties. For all slaves—regardless of gender, age, or health—the preparation of food meant work.

In the fields, women and men killed hogs, shelled corn, planted and gathered crops, dug holes for fence poles, and performed other seasonal agrarian duties. There was a hierarchy among domestic slaves. Scullions handled the menial tasks in the kitchen. Maids and houseboys assisted the butler, who guaranteed that meal times were coordinated.

The Washington Family/La Famille de Washington, Edward Savage, David Elkin, 1798

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Precision and exactitude

Servants’ skills were invaluable, as they worked as the conduits between dining rooms and kitchens in wealthy homes. At Mount Vernon, under the watchful eyes of Martha Washington, Frank Lee, the enslaved butler, supervised the maids and the waiters to ensure the table was properly set, and the house meticulously cleaned.

Chicken, ca. 2010

Image courtesy of Lori Dean Dyment

From bloody chicken to chicken dinner

A slave would chase, catch, and chop off the head of a chicken. Sometimes the animal would jump around without a head, spurting blood everywhere. After pulling pinfeathers, the chicken would be dressed—gizzards and liver removed—and either trussed (tied) so it cooked evenly over a spit, or the carcass cut into pieces for frying.

The Prudent Housewife, Or compleat English Cook; ..., Lydia Fisher, 1800

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Blended cooking styles leaves a legacy

In contrast to a single cooking method, Lucy Lee, one of several enslaved cooks at Mount Vernon, most likely blended African, Native American, and European styles of preparation and cooking, thereby leaving her imprint on Washington family meals.

The Complete English Cook; or, Prudent Housewife. . . ., Ann Peckham, 1767

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

When the cookbook is not enough

Lucy was skilled in preparing chicken for meals at Mount Vernon. She would use popular cookbooks or her own methods to fricassee or fry cut-up chickens. One of Martha Washington’s recipes required a half pound of butter.

Dinner plate, ca. 1778–1788

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

The house servant’s responsibility

Frank Lee, the enslaved butler, brought invaluable management skills to Mount Vernon. More than making sure the costly porcelain was well maintained, Frank helped safeguard the Washingtons’ ability to entertain in genteel society.

The Director: or, Young Woman’s best Companion. ..., Sarah Jackson, 1770

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

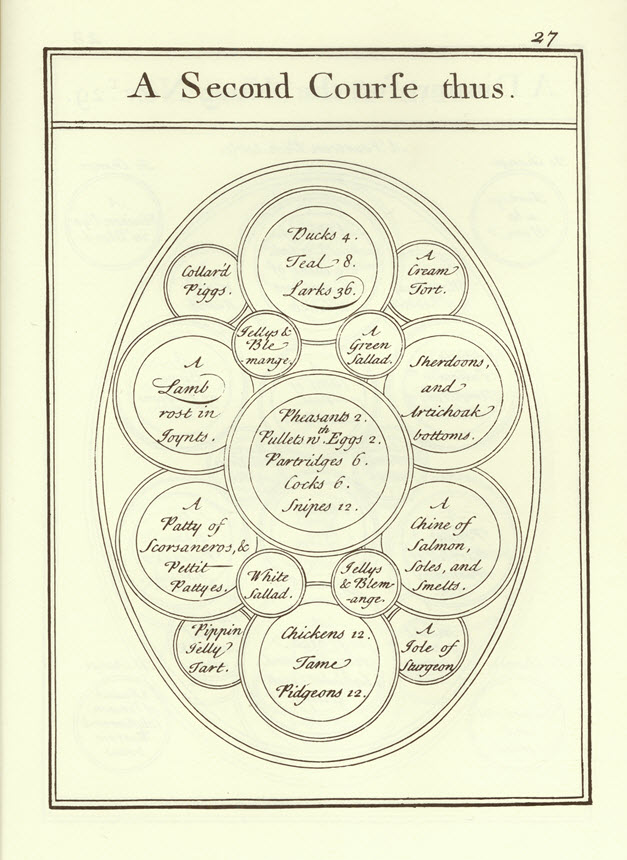

The Southern groaning board

Among privileged plantation owners, a sideboard weighted with an array of meats would be served along with an arrangement of vegetable side dishes. Formal dinners would use fine porcelain, crystal, and silver.

“A Second Course thus” from The Complete Practical Cook: or, new System of the Whole Art and Mystery of Cookery, Charles Carter, 1730

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Managing the dining room

Frank Lee, the butler, orchestrated meals at Mount Vernon with symmetry and exactitude. At the conclusion of each course, he removed soiled napery to reveal a new tablecloth.