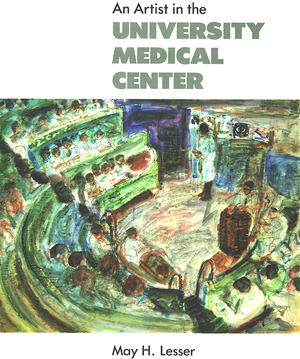

'Bull Pen'. From the cover of An Artist in the University Medical Center, also plate 1, page 10.

©May H. Lesser

This is the large weekly teaching conference for doctors-in-training and faculty -- called grand rounds. It's held in the old amphitheater of the public hospital, an austere place with brown, wooden bleacher seats whose tile backs seem to rise straight up from the floor, creating a cavelike atmosphere. Originally, this room was an operating room, designed to be hosed down with water after surgery. This was more than seventy years ago, during the time of Dr. Rudolph Matas, a professor at the medical school and a pioneer in vascular surgery. During the 1930s, when Dr. Alton Ochser was professor of surgery, it was nicknamed the "bull pen" for good reason: as a resident took center stage, to begin the ritual of presenting what he believed were the pertinent facts and findings in a patient's case, the prospect of being examined by the faculty in front of his colleagues made him feel like a bull in an arena. My husband and father both had vivid memories of this experience. Today's conference starts with a young doctor's description of the patient's illness and medical and family history. The doctor then reviews the results of his examination of the patient. As he shifts from human social history, his language shifts into the coded medical data of percentages, equations, and statistics. From this a diagnostic picture emerges that even I understand. The patient's liver feels like a large stone pressing into the right side of his abdomen. The diagnosis of cancer of the liver is ominous enough, but in addition he has pulmonary tuberculosis, as shown by the large white blob on his chest x-ray. The overhead lights are now turned off to show the slides from a biopsy of the patient's liver. A strange rose and purple-gray hue from the projector's light floats across the room, and suddenly all the doctors appear to have red halos, which splash on the gray tile walls. Next the view box shows a CAT scan. The curve of the bleachers is the same as that of the ribs on the film. And the shape of the lectern imitates that of the vertebra. During the ensuing discussion, the pulmonary specialist on the faculty argues that because the tuberculosis is advanced it should be treated before the cancer. Most participants agree. When the hands of the old clock in the front of the room reach noon, the hall rapidly empties. Only an ambulance siren penetrates the silence. Somehow it would be more appropriate to hear the bells of the horse-drawn ambulances in use when the room was built.

Last Reviewed: May 11, 2012