Exhibition Images

Image 19 of 43

Upon a View of the Body

Bloodstain, blisters, bullet holes, 1864

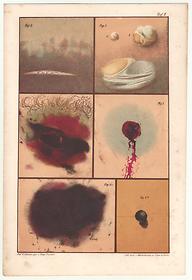

Fig. 2. Under the skin-cell tissue-hypostasis-death stains. Drawn 24 hours after death, from a pronounced spot on the back of a woman who died from an internal disease, on June 6, at a temperature of 16 degrees R. The incision made with a scalpel shows very faithfully a complete lack of blood infiltration into the cell tissue ("ecchymosed"), and moreover shows the blood spots from the severed veins, the unmistakable diagnostic sign of the death stains.

Fig. 3. Blisters resulting from burns sustained after death. Figures A and B show burst burn blisters created six hours after the death of a 20-year-old man by searing the outer surface of the upper arm with a spirituous flame. Only 30 hours later was the drawing completed. Figure C shows a larger burst burn blister which was created in the same manner thirty hours after death on the upper thigh of a woman who died insane. This drawing was not completed until 37 hours afterwards. When burns are inflicted on a corpse and cause rapidly bursting blister-shaped elevations on the outer skin, the drawing, just like nature itself, shows none of the known signs of the [equivalent] reactions on living tissue. In the cases drawn here, we intentionally left the burnt corpses exposed to the air for an extended period of time, but as the drawing reveals, as in our other experiments, we did not see even the smallest change in the burnt areas of skin [unlike living tissue].

Fig. 4. A [gunshot wound] entry opening. Fig. 5 is the exit opening of the shot which a 45 year-old male suicide inflicted upon himself in May in wet cool weather, lying on his back on a sofa. The (usually round) pistol bullet entered the area of the heart on the left between the fifth and the sixth rib and exited on the back between the tenth and eleventh rib. The breast hair in the vicinity of the wound and the hair on the goatee were burnt. The shot entirely tore apart the heart, the liver, the diaphragm. There was a general anemia in the entire body, namely the vena cava was completely drained. (Nevertheless there were found, even in this case, very visible brain hypostasis and very strongly marked death spots on the back.) The drawing was made three days after death, while the corpse was still fresh.

Fig. 6. A 22-year-old clerk had shot himself standing up in the Tiergarten (Berlin) on July 5, using a pointed bullet, and fell forward, dead, onto the ground. The shot entered the area of the heart, tore apart the heart and the left lung, and got lodged in the cartilage between the seventh and eighth vertebrae. The drawing was made on [July] 7th and the bullet is shown here in its precise shape and dimensions. The prominent difference between the wound from a pointed bullet and a rounded bullet becomes very clear from comparing figures four and six.

Fig. 3. Blisters resulting from burns sustained after death. Figures A and B show burst burn blisters created six hours after the death of a 20-year-old man by searing the outer surface of the upper arm with a spirituous flame. Only 30 hours later was the drawing completed. Figure C shows a larger burst burn blister which was created in the same manner thirty hours after death on the upper thigh of a woman who died insane. This drawing was not completed until 37 hours afterwards. When burns are inflicted on a corpse and cause rapidly bursting blister-shaped elevations on the outer skin, the drawing, just like nature itself, shows none of the known signs of the [equivalent] reactions on living tissue. In the cases drawn here, we intentionally left the burnt corpses exposed to the air for an extended period of time, but as the drawing reveals, as in our other experiments, we did not see even the smallest change in the burnt areas of skin [unlike living tissue].

Fig. 4. A [gunshot wound] entry opening. Fig. 5 is the exit opening of the shot which a 45 year-old male suicide inflicted upon himself in May in wet cool weather, lying on his back on a sofa. The (usually round) pistol bullet entered the area of the heart on the left between the fifth and the sixth rib and exited on the back between the tenth and eleventh rib. The breast hair in the vicinity of the wound and the hair on the goatee were burnt. The shot entirely tore apart the heart, the liver, the diaphragm. There was a general anemia in the entire body, namely the vena cava was completely drained. (Nevertheless there were found, even in this case, very visible brain hypostasis and very strongly marked death spots on the back.) The drawing was made three days after death, while the corpse was still fresh.

Fig. 6. A 22-year-old clerk had shot himself standing up in the Tiergarten (Berlin) on July 5, using a pointed bullet, and fell forward, dead, onto the ground. The shot entered the area of the heart, tore apart the heart and the left lung, and got lodged in the cartilage between the seventh and eighth vertebrae. The drawing was made on [July] 7th and the bullet is shown here in its precise shape and dimensions. The prominent difference between the wound from a pointed bullet and a rounded bullet becomes very clear from comparing figures four and six.

Johann Ludwig Casper, M.D., Atlas zum Handbuch der gerichtlichen Medicin [Atlas for the Manual of Legal Medicine], (4th ed., Berlin, 1864) [chromolithograph]; Artist: Hugo Troschel; Lithographer: Winckelmann & Sons

National Library of Medicine