Exhibition Gallery

Exhibition Gallery

The interior of our bodies is hidden to us.

What happens beneath the skin is mysterious, fearful, amazing. In antiquity, the body’s internal structure was the subject of speculation, fantasy, and some study, but there were few efforts to represent it in pictures. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century—and the cascade of print technologies that followed—helped to inspire a new, spectacular science of anatomy and new, spectacular visions of the body. Anatomical imagery proliferated, detailed and informative but also whimsical, surreal, beautiful, and grotesque—a dream anatomy that reveals as much about the outer world as it does the inner self.

Over the centuries, anatomy has become a visual vocabulary of realism. We regard the anatomical body as our inner reality, a medium through which we imagine society, culture, and the human condition.

Drawn mainly from the collections of the National Library of Medicine, Dream Anatomy shows off the anatomical imagination in some of its most astonishing incarnations, from 1500 to the present.

The interior of our bodies is hidden to us.

What happens beneath the skin is mysterious, fearful, amazing. In antiquity, the body’s internal structure was the subject of speculation, fantasy, and some study, but there were few efforts to represent it in pictures. The invention of the printing press in the 15th century—and the cascade of print technologies that followed—helped to inspire a new, spectacular science of anatomy and new, spectacular visions of the body. Anatomical imagery proliferated, detailed and informative but also whimsical, surreal, beautiful, and grotesque—a dream anatomy that reveals as much about the outer world as it does the inner self.

Over the centuries, anatomy has become a visual vocabulary of realism. We regard the anatomical body as our inner reality, a medium through which we imagine society, culture, and the human condition.

Drawn mainly from the collections of the National Library of Medicine, Dream Anatomy shows off the anatomical imagination in some of its most astonishing incarnations, from 1500 to the present.

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

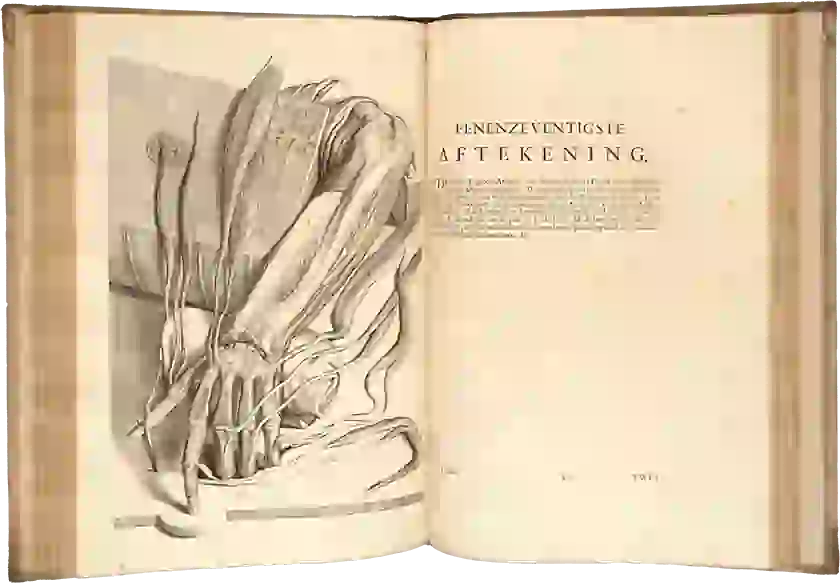

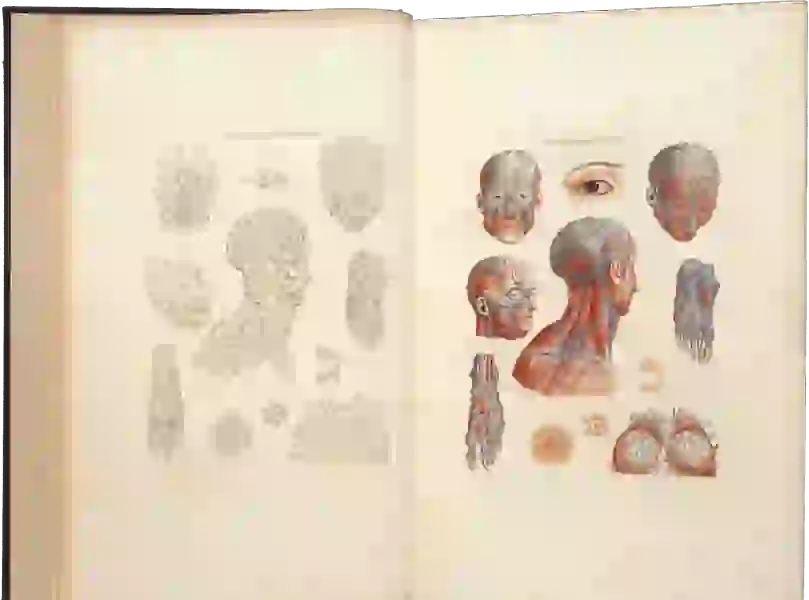

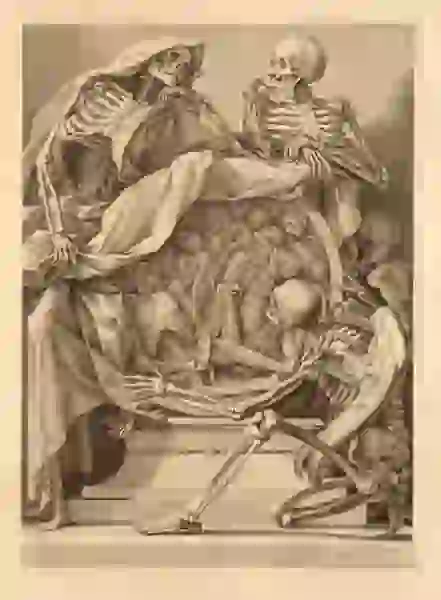

Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams..., Amsterdam, 1690

Bidloo’s realistic anatomy has affinities to trompe l’oeil and still-life, two popular genres of 17th-century Netherlandish painting that often featured bones and other symbols of death.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

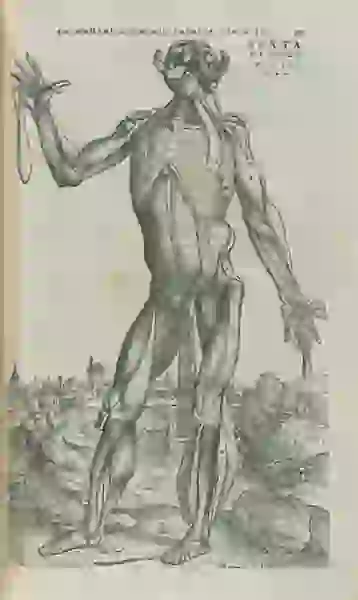

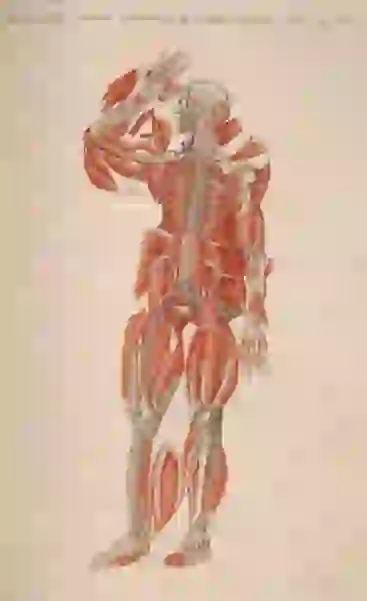

A compleat treatise of the muscles, as they appear in the humane body, and arise in dissection..., London, 1681

The dissection of the legs evokes the stylish cut of men’s knee breeches and hose.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Inside/Outside: Back, San Francisco, 1994

Katherine Du Tiel makes photographs of living bodies covered with projected anatomical images—a playful exploration of our continual attempts to synthesize the two, or perhaps an ironic comment on the impossibility of synthesis.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dream Anatomy: Introduction

Imaging Technologies

The interior of our bodies is hidden to us. What happens beneath the skin is mysterious, fearful, amazing. In antiquity, the body's internal structure was the subject of speculation, fantasy, and some study, but there were few efforts to represent it in pictures. The invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century—and the cascade of print technologies that followed—helped to inspire a new, spectacular science of anatomy, and new spectacular visions of the body. Anatomical imagery proliferated, detailed and informative but also whimsical, surreal, beautiful, and grotesque—a dream anatomy that reveals as much about the outer world as it does the inner self. Over the centuries anatomy has become a visual vocabulary of realism. We regard the anatomical body as our inner reality, a medium through which we image society, culture, and the human condition.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

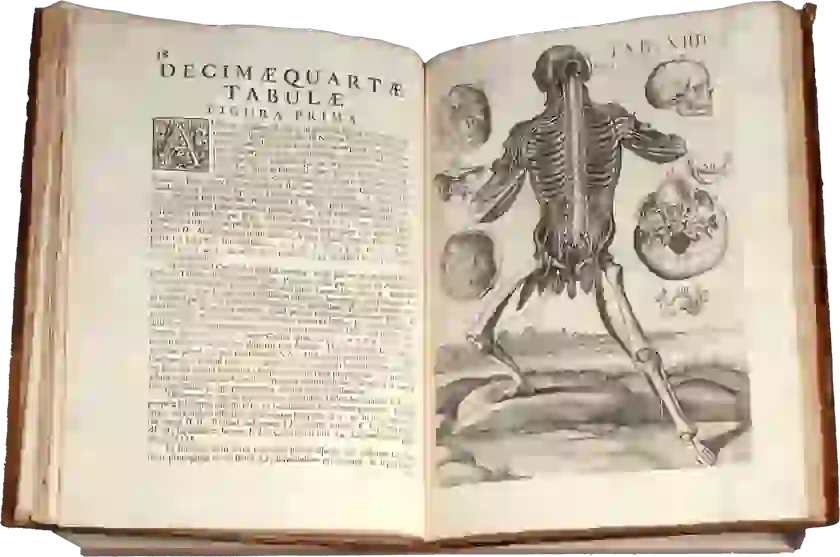

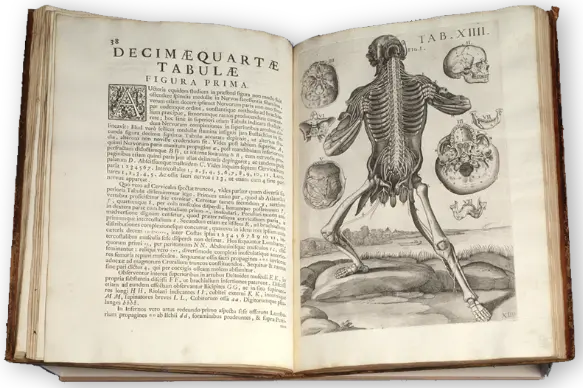

De Humani Corporis Fabrica..., Basel, 1543

Woodcut: To make a woodcut, an engraver starts by drawing an image, usually a tracing of a pencil drawing, onto the side grain of a wood plank. Areas not printed are cut away well below the surface with a knife or gouge, leaving the flat surface to be inked. Woodcuts can be put into type blocks along with moveable type, so that the image and type can be printed together in one run through the press. [Introduced into Europe: 1300s]

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

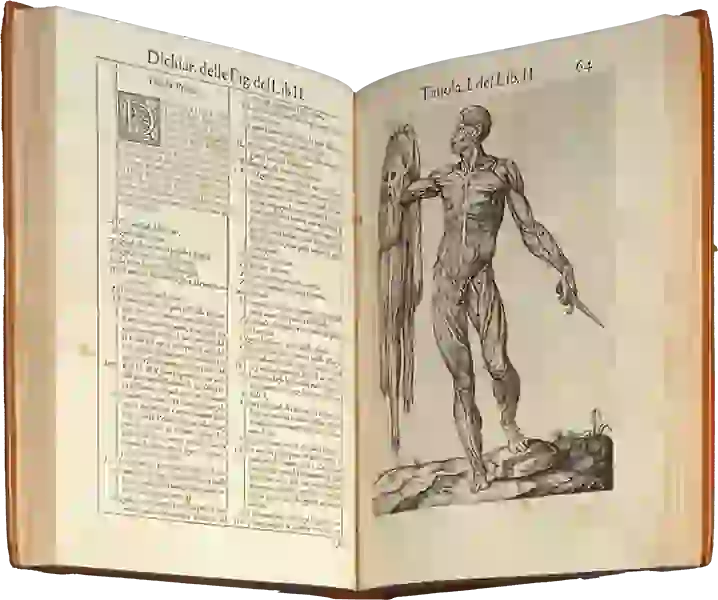

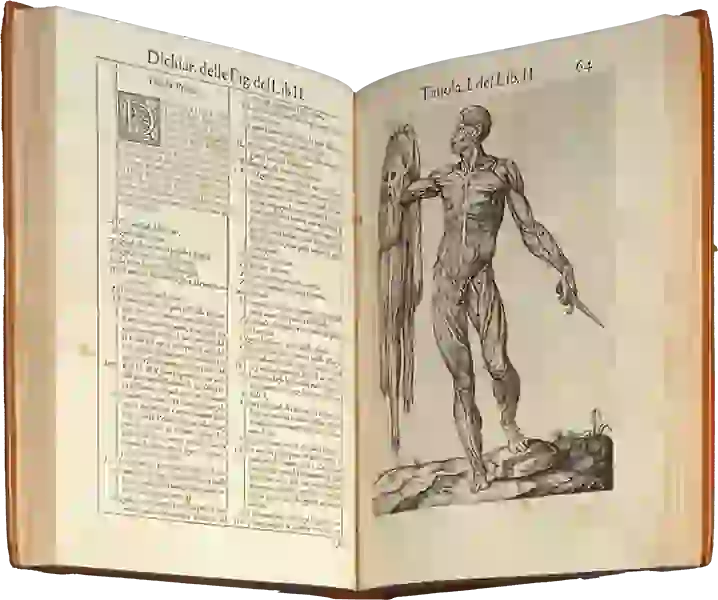

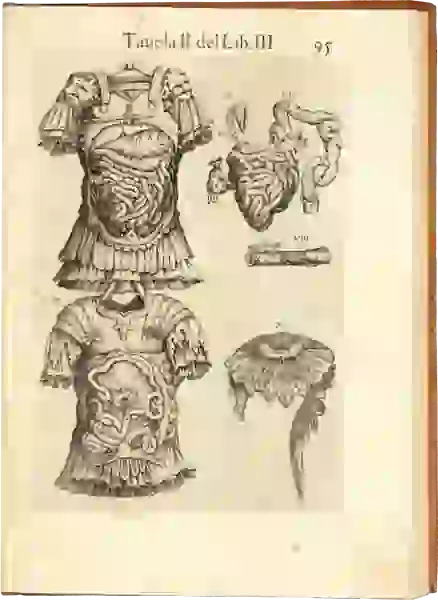

Anatomia del corpo humano..., Rome, 1559

Copperplate engraving: In copperplate engraving, an engraver copies a drawing onto the surface of a copper plate. Areas that will be white when printed are cut away below the surface with a sharp tool, leaving the flat surface to be inked. Copperplate engravings allow for finer lines and more detail than woodcuts, but the printing of the image requires more pressure than type or woodcuts (leaving a characteristic line of indentation around the image). Because of this difference in pressure, if moveable type on the page is desired then the page must be run through the press twice, once for the image and once for the type. [Invented: 1452]

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

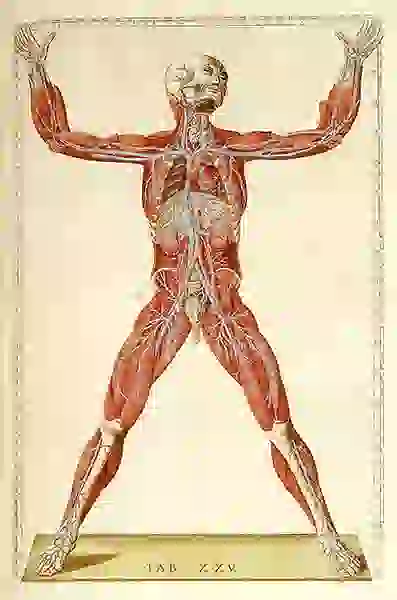

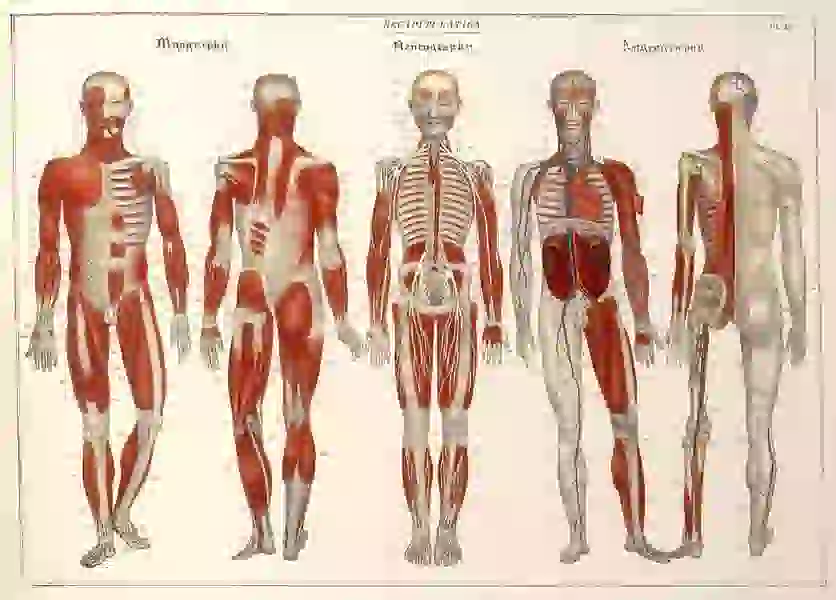

Romanae archetypae tabulae anatomicae novis..., Rome, 1783

Hand coloring: Before the invention of multiple-layer color printing, printed black ink anatomical illustrations were sometimes colored freehand, or in some cases, with a stencil, using tempera or watercolor.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Anatomie des parties de la génértion de l’homme et de la femme, Paris, 1773

Mezzotint: Unlike other engraving techniques, mezzotint proceeds from dark to light. A metal plate is completely abraded with a tool called a rocker. If inked and printed at this point, it produces an even, rich black. The design consists of areas of tone rather than lines, and is produced by smoothing areas of the plate with a scraper or a burnishing tool. The more scraping or burnishing, the lighter the area. The resultant illustrations have effects of light and shadow. By printing multiple color layers, different shades can be combined to produce rich hues that look much like oil paintings. [Invented: 1642]

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

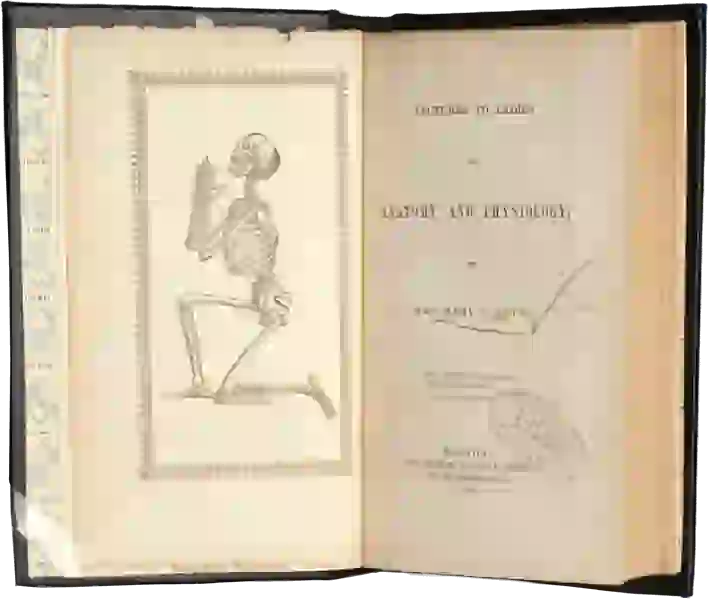

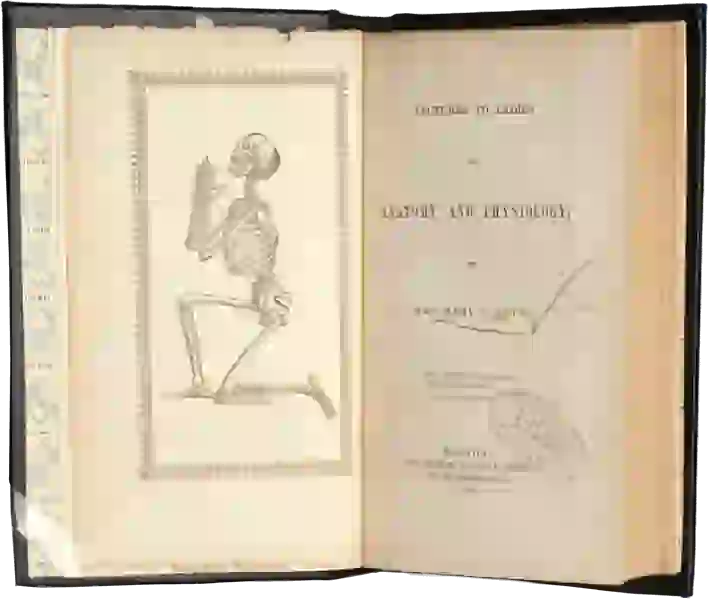

Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology, Boston, 1842

Wood engraving: In wood engraving, an engraver draws an image on polished blocks of dense end-grain wood (usually boxwood). Tools similar to metal engraving are used to produce non-printing lines. The uncut surface takes the ink and prints onto paper. The block can be inserted into a frame along with moveable type, and the entire page can be printed in one run through the press. The process allows for more detail than the older woodcut technique. [Invented: 1780s]

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 2

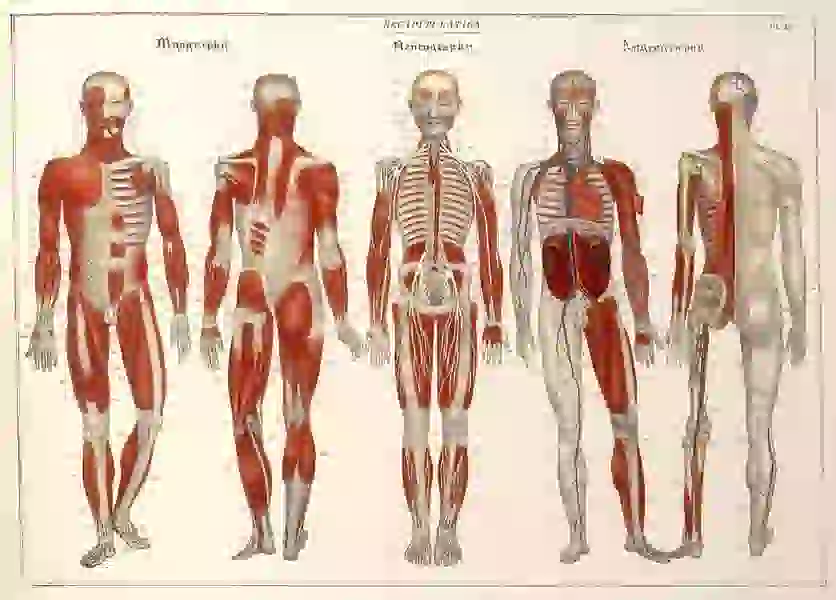

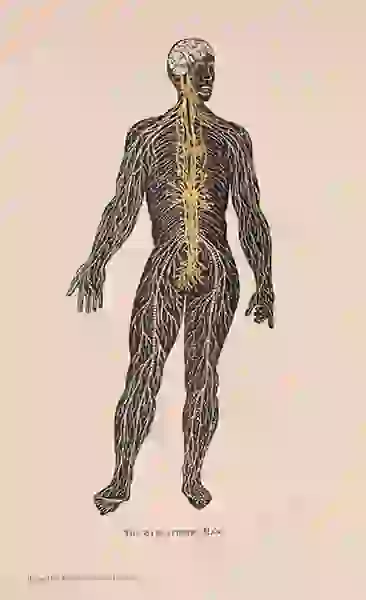

Systematized Anatomy; or, Human Organography, New York, 1837

Lithography: In lithography, a design is drawn or painted on a polished or grainy flat surface of a stone with a greasy crayon or ink. This image is chemically fixed on the stone with a weak solution of acid and gum arabic. The stone is flooded with water, which is absorbed everywhere except where repelled by the greasy ink. Oil-based printer’s ink is then rolled on the stone, which is repelled in turn by the water-soaked areas and accepted only by the drawn design. A piece of paper is laid on the stone and run through the press with light pressure. The design may be divided among several stones, properly registered, to produce a lithograph in more than one color through multiple printings on the same page. [Invented: 1798]

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 6 of 2

Inside/Outside: Muscle/Hand, San Francisco, 1994. Image © by Katherine Du Tiel

Photography: Photography is a process invented in the 1830s and 40s in which an image is produced on a chemically sensitized surface by the action of light. Unlike previous processes of anatomical representation, the image created is a "copy" of the subject, produced by technology, not recreated by the hand of an artist. [Invented: 1830s]

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 7 of 2

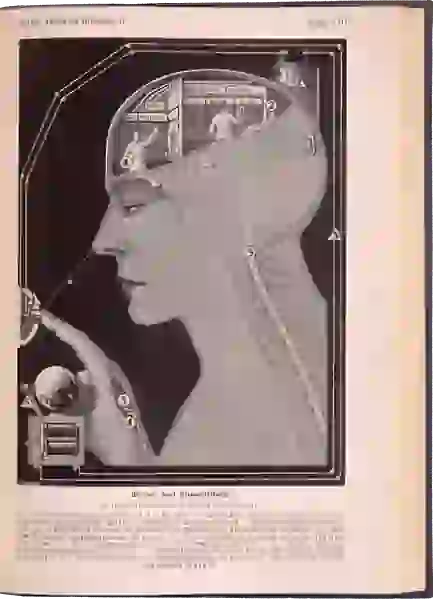

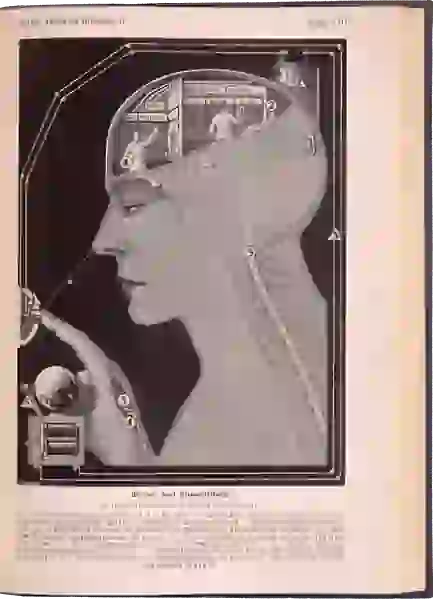

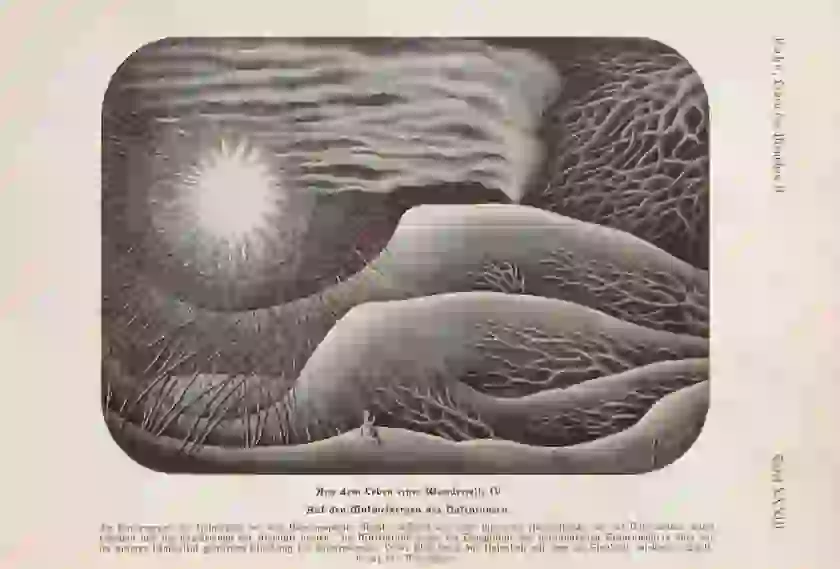

Das Leben des Menschen... (The Life of Man). Vol. 2, Stuttgard, 1926.

Relief halftone: Relief halftone is an industrial form of photo-etching. First, the artwork is photographed through a dot screen. The negative is exposed onto a zinc plate covered with light-sensitive gelatin. The picture is now converted into a dot pattern. The gelatin on the zinc plate is sensitized by the light through the negative in the shape of the line drawing, and the non sensitized gelatin is washed away. The sensitized area is then covered with a waxy substance resistant to acid; the rest of the plate is etched, so that the dot pattern appears in relief. The image then can be inked and printed onto paper. [Invented: 1880s]

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 8 of 2

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays, London, 1933

X-ray imaging: The x-ray is a form of radiation produced by accelerating a flow of electrons through a vacuum tube. In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen performed experiments showing that radiation emitted by this process could pass through flesh and other low-density substances that are opaque to ordinary light, but not bone. Röntgen discovered that x-rays could produce viewable images of the interior of the body on a photographic plate or on a screen with a fluorescent coating (“fluoroscope”). [Invented: 1895]

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 9 of 2

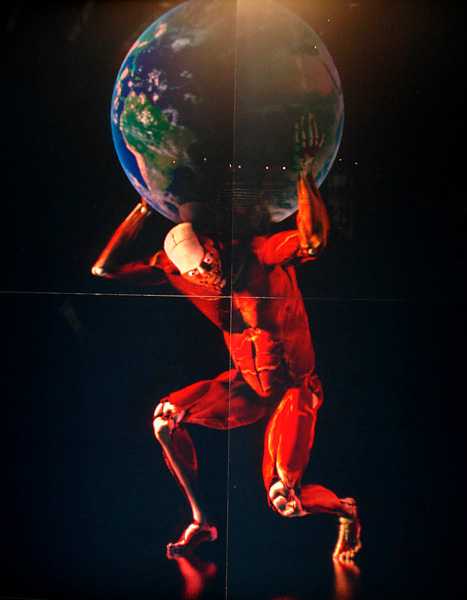

Visible Human as Atlas holding up the Earth, 2002

Digital imaging: Digitization is based on the idea that the continuous physical world of our experience can be divided into tiny pieces, and that these pieces can be measured and represented by a set of numbers. Color pictures can be digitized by measuring the color at closely spaced points (usually from 72 to 1200 dots per inch, or dpi). The color of each dot is then represented by three numbers indicating the combination of red, green, and blue that will reproduce the original color. Digital imaging is a powerful tool because numbers, unlike physical objects, can be reproduced perfectly, transmitted easily, and manipulated using computer programs.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Anatomical Dreamtime: The Early Modern Era

With the founding of the first medical schools in medieval Europe, anatomy ascended to a prominent position in the medical curriculum. Human dissection was performed as a ritual that illustrated the treatises of revered ancient authors—and that dramatized the power and knowledge of the medical profession. The mid-fifteenth-century invention of the printing press, and the rise of a new spirit of critical inquiry associated with the Renaissance, inspired a scientific revolution in anatomy. Anatomists began to dissect to investigate the structure of the body, and produced texts illustrated with images based on their dissections.

In the early modern era (1450–1750), the boundary between art and science was ill-defined. Anatomists and their artist collaborators made use of familiar modes of representation—the iconography of landscape, nudity, mythology, and Christianity. Artists tried to create illustrations that were accurate, but also amazing, beautiful, and entertaining.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

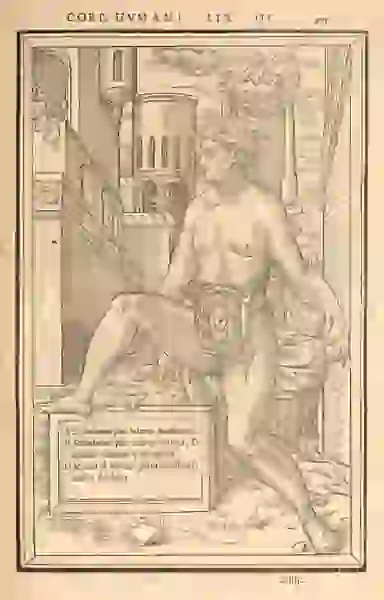

Anatomia del corpo humano..., Rome, 1559

A flayed cadaver holds his skin in one hand and a dissecting knife in the other. The skin’s distorted face has the appearance of a ghost or a cloud, suggesting that spirit has been separated from, or peeled off the fleshy inner man.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

De Humani Corporis Fabrica..., Basel, 1543

Anatomical representation makes the insides of our bodies visible and familiar, but also reveals a strangeness, an otherness. In dramatizing the dissected body, Vesalius contributed to a new visual iconography of monstrosity.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Tabulae Anatomicae, Venice, 1627

Early modern representations of the anatomical body took death head-on: the dead mocked the living; the living mocked the dead. The cadaver was an effigy of social types—the courtier, the flirt. Anatomy cited, parodied, or augmented long-established iconic traditions. This dissected figure evokes a distinctive pose—a not-so-subtle flirtation.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Anatomical Dreamtime: The Early Modern Era

Anatomical Primitives

The invention of the printing press in the 1450s, and the development of woodcut and copperplate engraving, made it possible to publish multiple copies of illustrated anatomies. Whimsical, surreal, beautiful, and often grotesque, the new anatomical images were rendered with varying degrees of skill and sophistication, in a hodge-podge of styles.

After the publication of the first modern anatomy, Andreas Vesalius’s revolutionary De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), illustrations in the Vesalian manner proliferated. But images with limited or no Vesalian influence continued to be featured in surgical manuals, almanacs, encyclopedias, and philosophical treatises, alongside discussions of astrology, alchemy, and theology.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Tashrih-i badan-i insan ca. 1400–1500

Fascination with the interior of the body goes back to the dawn of humanity.

This illustrated treatise on human anatomy consists of an introduction, five chapters on the five systems (bones, nerves, muscles, veins, and arteries) and a conclusion on the compound organs and embryology. This pre-modern manuscript is one of the first systematic works on human anatomy.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

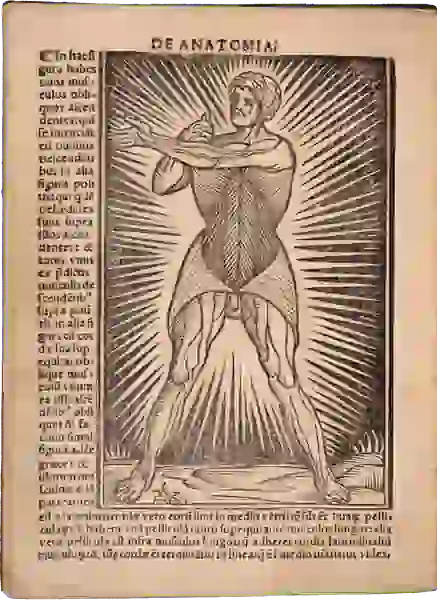

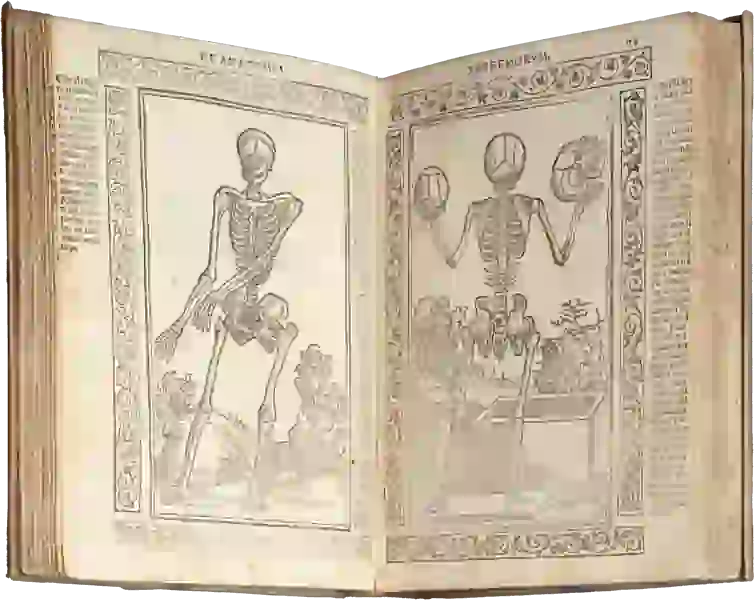

Anatomia Carpi. Isagoge breves perlucide ac uberime, in Anatomiam humani corporis..., Bologna, 1535

Berengario, an Italian surgeon and physician, refashioned the 14th-century anatomical treatise of Mondino de’Liuzzi for print publication. The illustrations give little anatomical detail, but visually represent the sense of wonder that attends the opening of the body.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

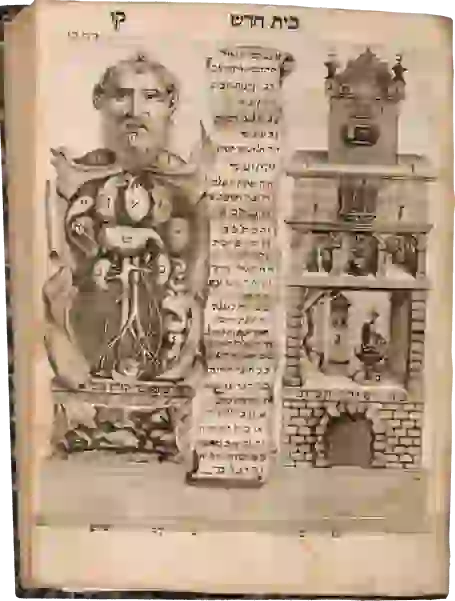

Ma’a’seh Toviyah, Venice, 1708

This illustration from a Hebrew encyclopedia pairs the interior of a human interior with the interior of a house, a visual metaphor: the organs, like rooms in a house, have different functions. Kats, one of the first Jews to study medicine at a German university, completed his degree at Padua and served as a court physician to the Ottoman Sultan.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Isagogae breves per lucidae ac uberrimae in Anatomiam human corporis..., Bologna, 1523

Berengario, who is said to have dissected hundreds of bodies, here presents and comments on the anatomy of Galen (ca. 130–ca. 200 A.D.), Mondino de’Liuzzi (d. 1326) and others. The crude, anatomically inaccurate illustrations borrow liberally from medieval death iconography.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

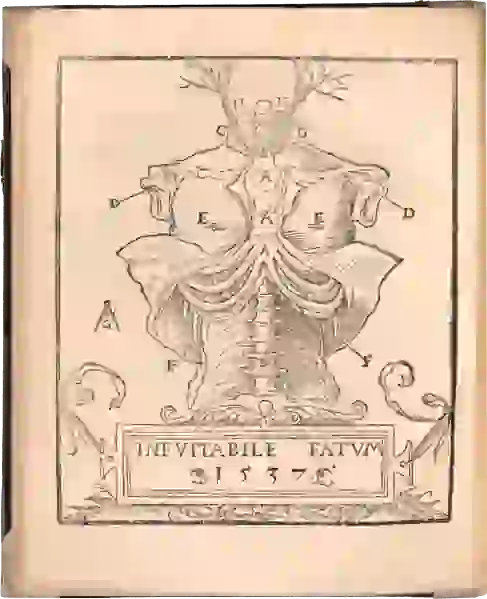

Anatomiae, hoc est, corporis humani dissectionis..., Marburg, 1537

Dryander, a German professor of anatomy, revised the works of Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (ca.1460–ca.1530) and Mondino de’Liuzzi (d. 1326). Here, a torso serves as an anatomical coat of arms. The phrase "INEVITABILE FATUM" (inevitable fate) links the illustration to the iconography of death: the dissected body and skeleton remind us of our mortality.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Anatomical Dreamtime: The Early Modern Era

Cadavers at Play

Charles Estienne’s 1545 De dissectione partium corporis (On the dissection of the parts of the human body) would have been the first lavishly illustrated anatomy, had publication not been delayed by a lengthy legal dispute with collaborator Étienne de la Rivière. The woodcuts, while imaginative, lack the rigor and detail of Andrea Vesalius’s 1543 De Fabrica—and unlike De Fabrica, posed no challenge to the authority of the ancient anatomists. To cut costs, Estienne took some of his illustrations from non-anatomical books, replacing the middle of the woodblock with an insert that depicted the body’s interior.

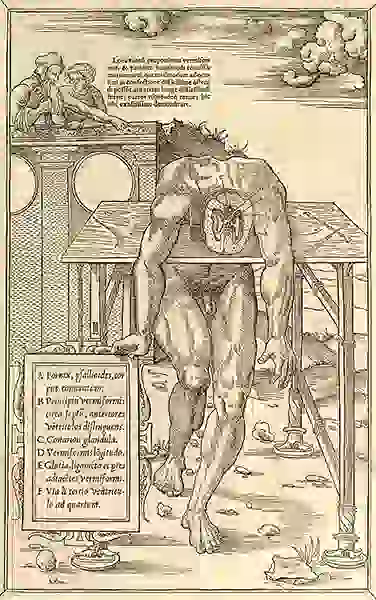

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

De dissectione partium corporis humani..., Paris, 1545

Draped over a table, an anatomical figure displays a cross-section of his brain while touching a frame that holds captions. In the background, spectators observe from atop a fanciful parapet. To cut costs, Estienne took some of his illustrations from non-anatomical books, replacing a section of the woodblock with an insert that depicted the body's interior. In this figure, the boundary of the insert is seen in a square around the head.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

De dissectione partium corporis humani..., Paris, 1545

The anatomical figure sits on a fanciful throne, with a leg casually propped up on the framed caption. In the upper left, a solitary figure looks on from atop a parapet. To cut costs, Estienne took some of his illustrations from non-anatomical books, replacing a section of the woodblock with an insert that depicted the body's interior. In this female figure, the boundary of the insert is revealed by a faint white line under her left arm.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

De dissectione partium corporis humani..., Paris, 1545

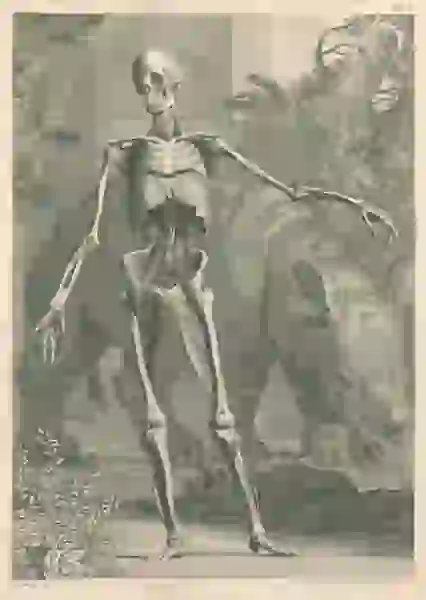

A skeleton with a thin covering of tendons poses before an apocalyptic sky.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Anatomical Dreamtime: The Early Modern Era

Arts and Sciences

In 1543 Andreas Vesalius produced De Humani Corporis Fabrica, the first profusely illustrated anatomy book. A brilliant dissector, the 28-year-old Vesalius insisted that reliable knowledge derives from examination of cadavers, not ancient texts. He subjected the old anatomical treatises to a rigorous test: a comparison with direct observations of the dissected body. De Fabrica became the founding text of modern anatomy and inspired a host of successors. Like Vesalius, they compared their results with existing texts, corrected errors, and produced new texts with illustrations. The production of images based on dissection became a central component of scientific anatomy.

De Fabrica inspired other anatomists to attempt their own books.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

De Humani Corporis Fabrica..., Basel, 1543

Vesalius dissects a cadaver in the center of a crowded anatomical theater, while Death hovers over the scene. Before De Fabrica (1543), depictions of dissection had the anatomist presiding at some distance from the cadaver, while lower ranking barber-surgeons did the dirty work of dissecting.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

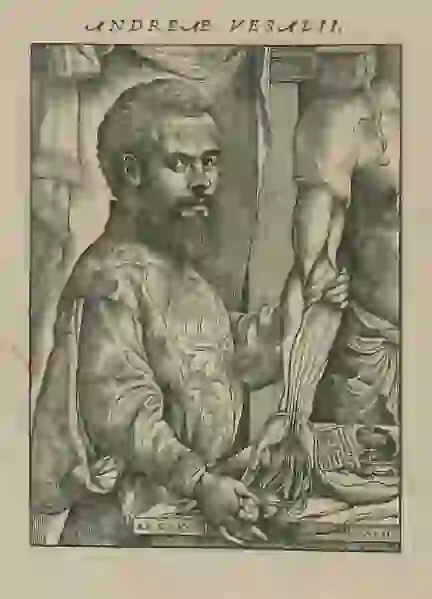

“Andreas Vesalius”, De Humani Corporis Fabrica..., Basel, 1543

The only known first-hand likeness of Vesalius shows the formally attired anatomist grasping the dissected arm of a cadaver. Vesalius’s head is disproportionately large compared to his body, but the cadaver is larger still—leading to speculation that the engraver pulled the composition together from several sources.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

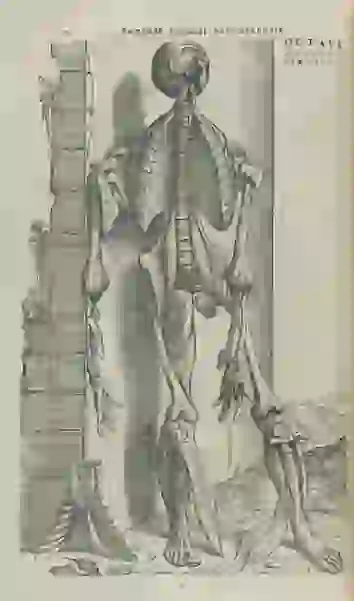

De Humani Corporis Fabrica..., Basel, 1543

A ruined body leans against ancient ruins, a metaphoric echo. Here, visual metaphor coexists with a commitment to accurate naturalist depiction.

Vesalius collected and presented his findings in De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543), a book of more than 600 pages, with beautifully detailed woodcuts by artists from the workshop of Titian. The illustrations set a new standard for accuracy, while drawing on a variety of contemporary genres of visual representation: naturalism, classicism, metaphor, landscape, death imagery and monstrosity.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 1

Joannes Valverdus Hispanus (ca. 1525–ca. 1588)

Juan Valverde de Amusco studied with Realdo Columbo, Vesalius’s pupil and successor. His Historia de la composición del cuerpo humano (1556) was the first anatomy published in Spanish. Valverde used Vesalius’s work as a departure for his own anatomical visions, which humorously played on identifications of self and other, and matter and spirit.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

Historia de la composición del cuerpo humano, 1556

Valverde playfully shows the viscera dissected not just through skin, but through a suit of Roman armor. The free-floating body parts on the right are copied from Vesalius.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

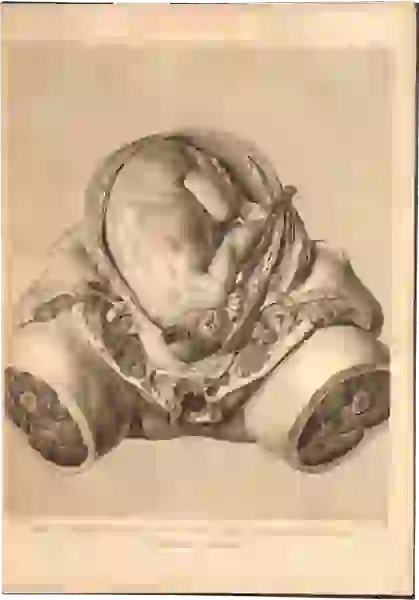

Anatomical Dreamtime: The Early Modern Era

Body Part as Body Art

In the late 1600s, a new anatomical art-form emerged: the specimen. Anatomists began to collect and exhibit bodies and body parts. Their specimens were real—and they dazzled viewers. Like wax and marble, the human body served as a sculptural medium. The anatomist preserved this material, and then colored, costumed, and arranged it in glass cases or free-standing displays.

Anatomists produced objects in different media. "Natural" preparations, made from human or animal bodies, could be "wet" (submerged in alcoholic preservative in sealed jars) or "dry" (injected with resins, or wax and then dried). Anatomists also made "artificial" preparations, from wax, plaster, paper mâché, and other materials.

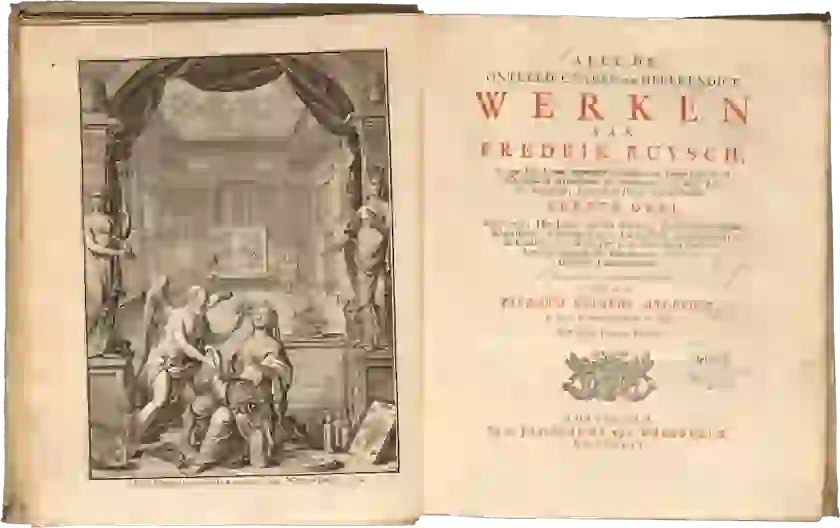

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 1

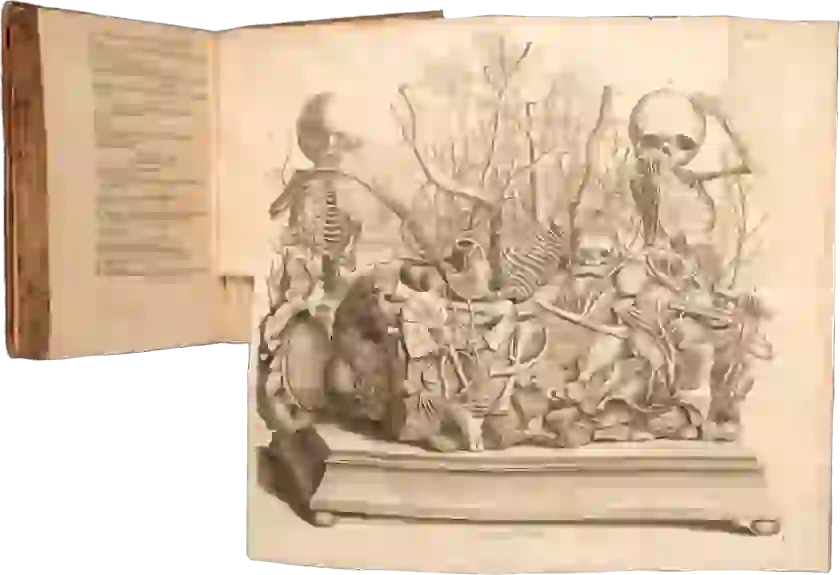

Alle de ontleed- genees- en heelkundige werken.... Vol. 1., Amsterdam, 1744

Ruysch was the first great exponent of the anatomical specimen. Visitors from all over Europe came to marvel at his "repository of curiosities." As Amsterdam’s chief instructor of midwives and "legal doctor" to the court, Ruysch had ample access to the bodies of stillborns and dead infants and used them to create extraordinary multi-specimen scenes. In making such displays, he claimed an extraordinary privilege: the right to collect and exhibit human material without the consent of the anatomized.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Alle de ontleed- genees- en heelkindige werken.... Vol.2, Amsterdam, 1744

Ruysch festooned infant skeletons with various objects, organic and non-organic, and arranged them in landscapes of body parts.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

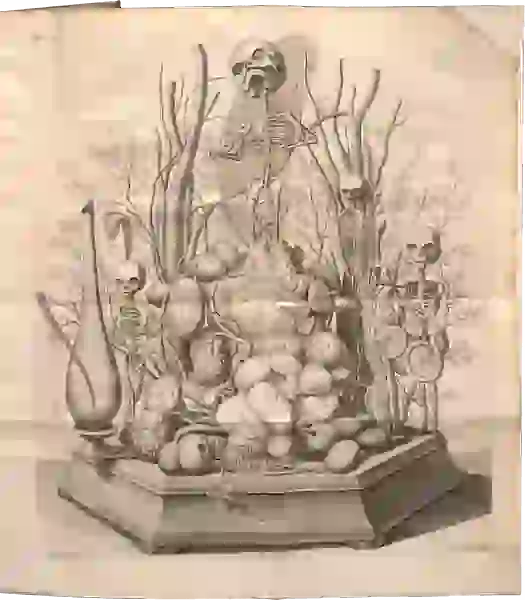

Alle de ontleed- genees- en heelkindige werken.... Vol. 2, Amsterdam, 1744

Ruysch’s "repository of curiosities" included displays of infant and fetal skeletons, placed in landscapes of human and animal body parts. This ghastly musicale is notable for its morbid whimsy.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Frontispiece and title page, Alle de ontleed- genees- en heelkundige werken.... Vol. 1., Amsterdam, 1744

Early modern anatomical illustrations and objects operated in multiple meanings and served multiple functions. The anatomist studied dissected cadavers and enjoyed manipulating and presenting them; readers and viewers studied dissected cadavers and enjoyed looking. This convergence of work and play, this multiplicity of function and meaning, was not problematic.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Anatomical Dreamtime: The Early Modern Era

Show-off Cadavers

The emergence of anatomical illustration in the period of 1500–1750, coincided with a larger phenomenon, a new definition of personhood that was performed at court, in salons, coffeehouses, country estates, theaters, and marketplaces. Inevitably, anatomists took up, commented on, and played with, the contemporary obsession with self-fashioning and individuality—it was an era of manners, wit, foppishness, and coquetry. In the works of Giulio Casserio, John Browne and Pietro da Cortona, the illustrated anatomy book is a stage featuring posing, prancing cadavers. Animated with an exuberant vitality, the corpses perform an anatomical show for the reader’s gaze.

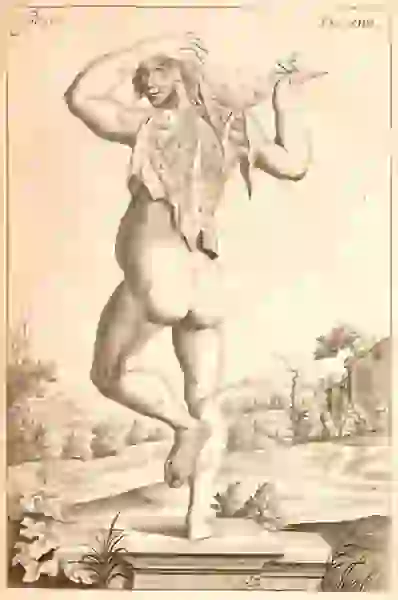

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

De humani corporis fabrica libri decem, lulii…, Venice, 1627

Some of Casserio’s plates stage a not-so-subtle flirtation. Here, the model coyly hides behind a veil of his own body tissue as he bares his innards.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

De formato foetu liber singularis, Padua, 1626

The plates for Casserio’s theatrum anatomicum were printed after his death in works attributed to him and his pupil Adriaan van Spiegel (1578–1625). Here, a pregnant woman is dissected so that the flaps resemble petals of a flower, with the baby at the center.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

De humani corporis fabrica libri decem, lulii…, 1627

Dressed in bonnets, sashes and undressed down to skin and layers beneath Casserio’s figures have the look of everyday people: peddlers, farmwives, artisans, laborers—an attempt at realism with a hint of comic exaggeration.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Tabulae anatomicae…, 1741

Around 1618, Berrettini made a series of extraordinary drawings that were later forgotten and only printed in 1741. The figures are emphatic anatomical entertainers who solicit attention with aggressive body language.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

Tabulae anatomicae…, 1741

A skeleton dances a lively step, while in the background an arrangement of bones float in the air. Berrettini’s exuberant flourishes take their cue from the theatrics of baroque drama and court entertainments.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 1

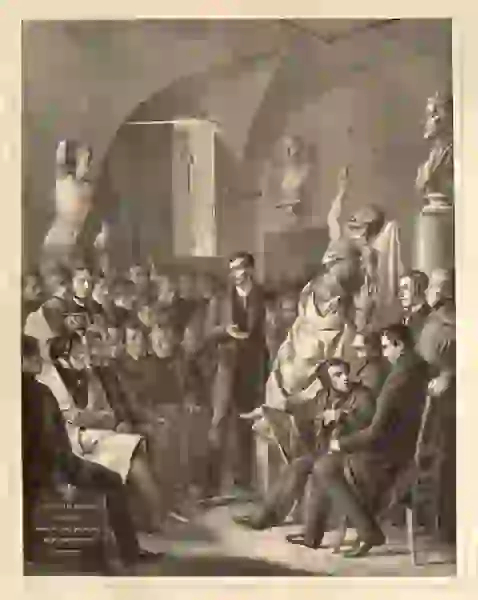

Myographia nova… (Compleate treatise of the muscles), 1687

Sporting a stylish hairdo of cascading curls, anatomist and author John Browne presides over a fanciful anatomy lesson.

Artists did not just record anatomical reality: they dramatized, travestied, beautified, and moralized it. In the time of Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), and for centuries after, the only legal source of bodies was the gallows. This was insufficient to meet the needs of anatomists, who often stole bodies from burial grounds. But the public regarded grave robbery and dissection as an insult to funerary honor and defended their dead—the dissection of bodies carried a stigma. Families and neighbors stood vigil over the dead and battled body snatchers. Anatomists, therefore, tended to take their subjects from the least powerful people—convicts, prostitutes, the poor.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 6 of 2

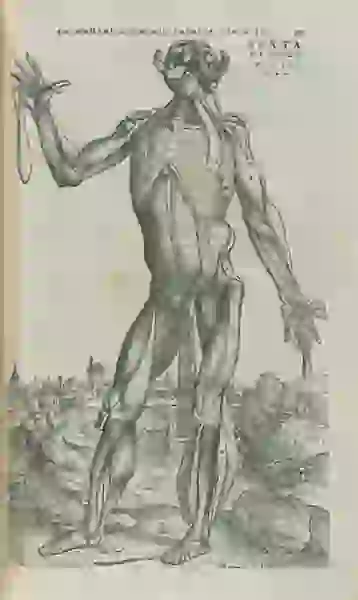

A compleat treatise of the muscles, as they appear in the humane body, and arise in dissection…, 1681

Browne’s figures dance and posture with theatrical gestures. Here, a seductive coquette flirtatiously displays her musculature.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 7 of 2

A compleat treatise of the muscles, as they appear in the humane body, and arise in dissection…, 1681

The figure of an anatomized courtier languorously postures atop an absurd pedestal. The overall effect is travesty.

The gulf between illustration and real life was vast. In reality, the nobility and gentry were protected from dissection—anatomists used the bodies of criminals, outcasts, and the poor. Illustrators typically suppressed these social origins, but in John Browne’s anatomy the despised lower-class cadaver is perversely transformed into a high-born courtier.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

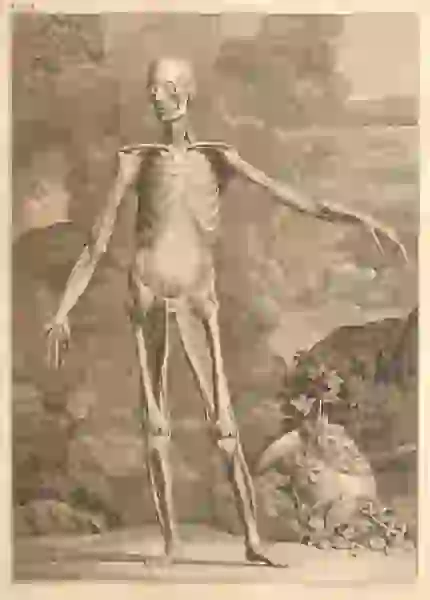

Getting Real: Removing Metaphor and Fancy

Removing Metaphor and Fancy

Between 1680 and 1800, anatomists began purging imaginative elements from scientific illustration. The truth value of anatomy, they argued, was compromised by visual metaphors, fantastic landscapes, and comic poses. As old print technologies were perfected and new ones invented, anatomical illustration began to achieve greater technical precision, and a brilliant, dreamlike hyper-aestheticism that showed off, with great artistry, a more sophisticated knowledge and heightened perception of the boundaries and surfaces of the body.

Ultimately, two styles of anatomical realism emerged. One aimed to show the reality of dissection, the cutting open of a particular body with all the prosthetics, furniture and setting of dissection—and the ugliness of anatomical mutilation. The other aimed to show a higher reality, displaying beautified, cleaned-up, idealized bodies and body-parts that float in air, with no reference to any one dissection.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Topographisch-anatomischer atlas: nach durchschnitten an gefrorenen cadavern, 1872

Braune’s atlas is notable for its beautiful color, harmonious composition, and extensive use of frozen cross-sections.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Anatomia uteri humani gravidi tabulis illustrate (The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus), 1774

An eminent anatomist and obstetrician, Hunter, confined himself to a specific topic (late pregnancy) and "subject" (the dissection of a woman who died near the end of term). Hunter argued illustrations that represent only "what was actually seen," will carry "the mark of truth" and be "almost as infallible as the object itself."

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams, 1690

This stark dissection—with ragged flesh fully displayed and hands bound with a cord—signals a commitment to a higher level of realism. To our eyes, the picture may suggest a distressing indifference to, or even pleasure in, human suffering.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Getting Real: Removing Metaphor and Fancy

Monumental Books

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the development of mezzotint, and printing methods that combined etching and engraving, made it possible to make anatomical illustrations of startling beauty and painterly texture. Published in monumental scale and on fine paper, these plates were spectacles of anatomical science, artistry and advanced print technology—the final act of anatomy’s theatrical tradition. Their intended audience was an elite group of wealthy men of learning and discernment. Two notable exponents of this extravagant anatomy were the German anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697–1770) and French artist-printer-publisher Jacques Fabien Gautier d’Agoty (1711–1785).

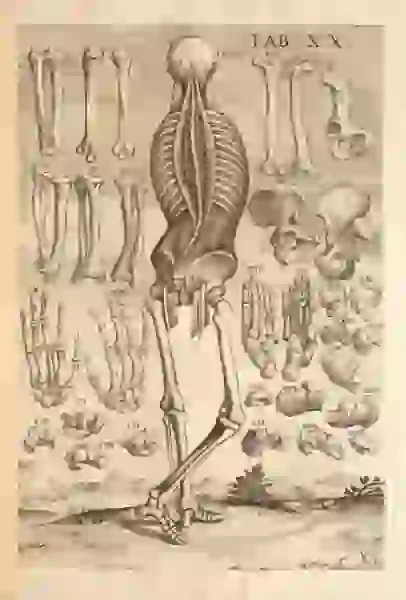

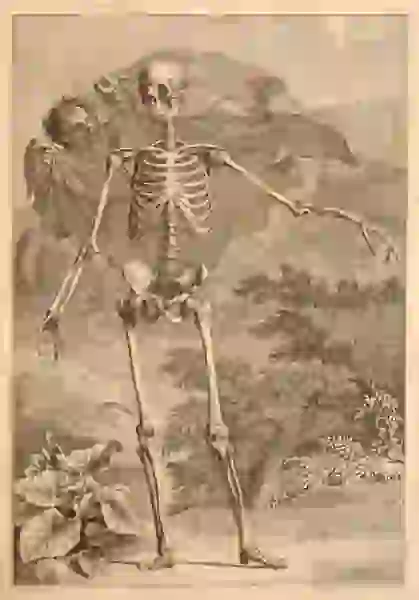

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani, 1749

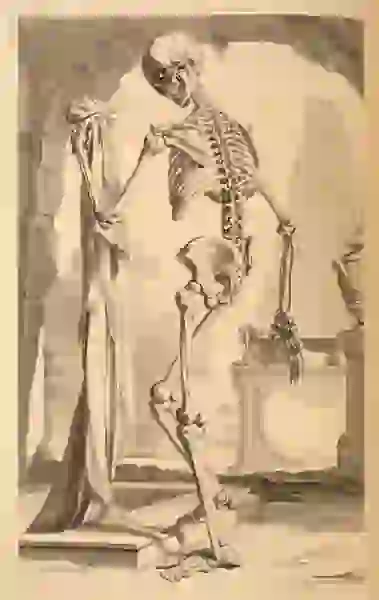

Albinus, professor of anatomy at Leiden, proposed in the 1720s to make the most detailed, beautiful, and comprehensive anatomical atlas ever published, using stylized figures representing an ideal humanity. He never completed the project, but did finish a part, Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani (1747)—the last great medical anatomy to use imaginative elements.

Albinus intended his figures to exemplify ideal humanity and an ideal of anatomical illustration. The cadaver, carefully chosen for its close approximation to classical ideals of proportion, stands with a guardian angel hovering behind against a painterly backdrop.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani, 1749

Wandelaar’s backgrounds are intended to be both beautiful and poetically evocative, a meditation on nature and mortality that complements the idealized figure of humanity.

According to Albinus, the poetically evocative backdrops were designed to "agreeably" fill "the empty spaces" and make the figure look three-dimensional. Later editions omit the backgrounds, a concession to the movement.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Tabulae Sceleti e Musculorum Corporis Humani, 1749

In an attempt to increase the scientific accuracy of anatomical illustration, Albinus and Wandelaar devised a new technique of placing nets with square webbing at specified intervals between the artist and the anatomical specimen and copying the images using the grid patterns. Tabulae was highly criticized, especially for the whimsical backgrounds added to many of the pieces by Wandelaar, but Albinus staunchly defended Wandelaar and his work.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

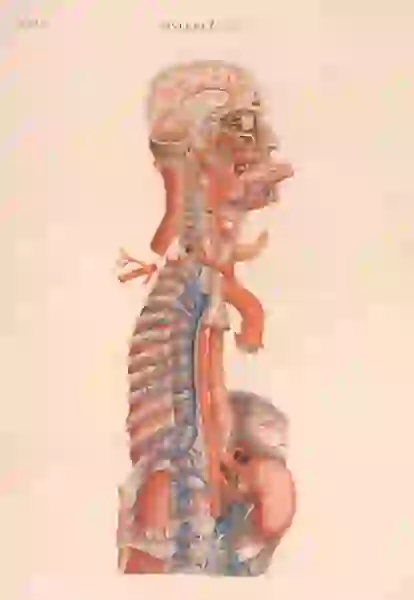

Anatomie des parties de la génération de l’homme et de la femme, Paris, 1773

D’Agoty’s colored mezzotints have a painterly quality. This pregnant woman calmly looks back at the viewer, a characteristic pose of 18th-century French portraiture.

Gautier d’Agoty perfected a method of printing colored layers of mezzotint (a technique that allows for subtle gradations of shading). The resultant anatomical illustrations look like paintings on a page, and are remarkable for their brilliance, gaiety, eccentricity, delicacy, and (paradoxically) crudity.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

Anatomie des parties de la génération de l’homme et de la femme, Paris, 1773

D’Agoty’s large plates can be pasted together to form life-size figures.

As a subject, anatomy was particularly well suited to display Gautier d’Agoty’s mastery of advanced print technology. It also gave him license to show parts of the body not permitted in other genres of illustration. The aim was to dazzle more than to instruct.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 2

Anatomie des parties de la génération de l’homme et de la femme, Paris, 1773

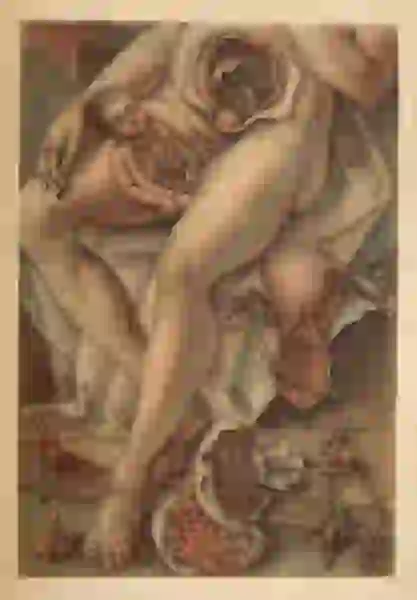

The grotesquerie of subject matter, stiffness of the figure, and eccentric arrangement of body parts make for a characteristic dreaminess that eerily anticipates 20th-century modernism.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Getting Real: Removing Metaphor and Fancy

Beautiful Ugliness

With Dutch anatomist Govard Bidloo (1649–1713), anatomical representation entered a new era. Some plates retained iconographical elements, but most were devoid of landscape, metaphor, and classicism. With high artistry, Bidloo flaunted his commitment to empirical observation and naturalistic depiction by showing what other anatomies omitted: the prosthetics of dissection (ropes, props, nails, chains) and the mutilation and ugliness of the dissected body. In producing such images, the anatomist claimed the power to appropriate, and cut into, dead human beings—and demonstrated a masterful clinical detachment, a privileged indifference to the horrors of the anatomy room.

Scottish anatomist John Bell (1763–1820) condemned artists and their "vitious practice of drawing from imagination." There was, he insisted, a "continual struggle between the anatomist and the painter, one striving for elegance of form, the other insisting upon accuracy of representation." He solved the problem by drawing, etching and engraving his own illustrations. These challenged nearly every convention of anatomical representation. His dissected bodies and parts lack sumptuous texture and graceful line and are unleavened by any palliative beauty. Their remarkable ugliness underscored his unyielding allegiance to tough-minded empirical observation.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams..., 1690

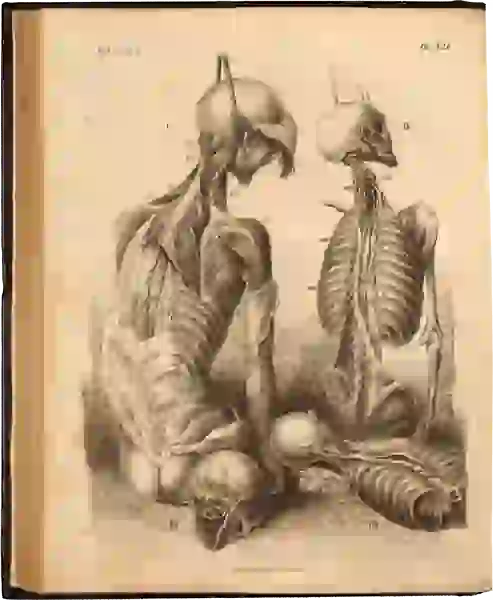

The mutilation of the dissected face, and depiction of the nails and pins that serve as prosthetic aids to anatomical study, demonstrate Bidloo’s unsparing anatomical realism.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams..., 1690

On some pages, de Lairesse commingles body parts with objects taken from everyday life, a variation on the still life, a popular genre of northern European painting that often contained skulls and other allusions to human mortality.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Ontleding des menschelyken lichaams..., 1690

Bidloo’s anatomy represents a transitional stage. Alongside harshly realistic illustrations, he offers a few memento mori (reminders of mortality).

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Engravings of the bones, muscles, and joints, illustrating the first volume of the Anatomy of the Human Body. 2d ed., London, 1804

Bell criticized "the subjection of true anatomical drawing to the capricious interference of the artist, whose rule it has too often been to make all beautiful and smooth, leaving no harshness…." His own drawings and etchings are notably harsh.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Getting Real: Removing Metaphor and Fancy

The Colorized Human

By the late 1700s, the commitment to empirical representation of the body was increasingly asserted by an obsessive attention to detail that went beyond realism. The anatomy of the 1800s featured fine line, rich texture, and, in much of the material, intense color. In realistic rendering, detail is often obscured—the eye can’t make certain things out. In the hyper-realism of the new anatomy, detail stands out in shocking, dream-like clarity, a demanding visual effect that requires sophisticated artistry and a deeper understanding of bodily structure and function derived from pathological anatomy. In much of hyper-realist anatomy, the image is a composite, idealized, and beautified body; the process of dissection and setting of the anatomy room are suppressed as an unnecessary distraction.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Anatomia universal del Paolo Mascagni, 1833

Mascagni’s great anatomical atlas was published only after his death. A lithographic 1826 edition claims Corsican anatomist Francesco Antommarchi (Napoleon’s personal physician, and Mascagni’s sometime collaborator) as the sole author. But scholars recognized the searingly bright colors and stylized grotesquerie of the figures as the distinctive work of Mascagni.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Anatomia universal del Paolo Mascagni, 1833

In the omission of background, and intense, even excessive, use of color, Mascagni’s plates exemplify the new free-floating style of anatomical representation. The rendering of dissected "flaps," however, harkens back to an older style.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Anatomia universal del Paolo Mascagni, 1833

Mascagni developed new methods of anatomical preservation, made important contributions to the understanding of human lymphatics, and produced a comprehensive and unprecedented series of brilliantly colored, oversized, anatomical plates.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

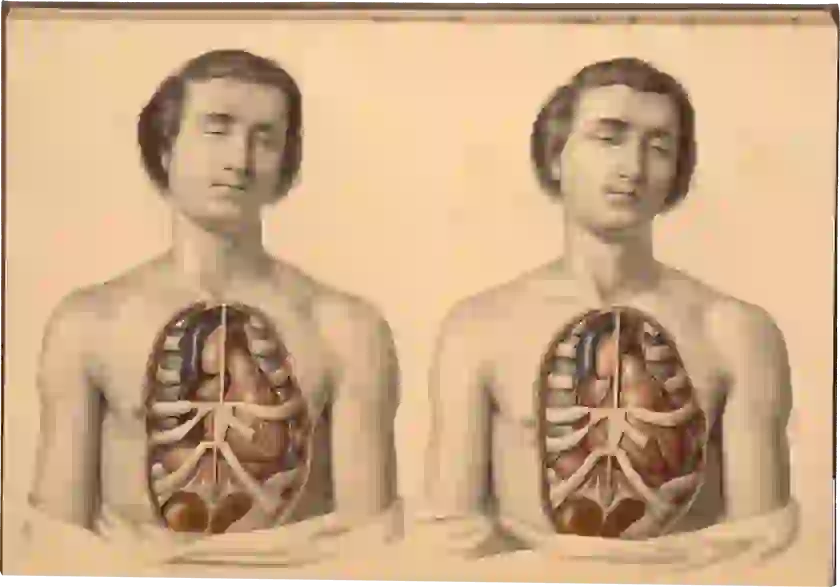

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Medical anatomy..., 1869

Sibson argued that anatomical illustrations are misleading because preservative injections and the dissection itself change the relative position of parts. This double illustration is intended to show a true picture of the dead body alongside an imaginative reconstruction of the same interior in a living body.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

Illustrations of dissections in a series of original coloured plates, the size of life, representing the dissection of the human body..., 1867

Subdued color and shading, and masterful composition, lend the dissected body and prosthetics of dissection a serene beauty.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 5 of 2

Systematized Anatomy; or, Human Organography, New York, 1837

Sarlandière, an enthusiastic practitioner of electromagnetic therapy and phrenology, and a follower of the utopian socialist Saint-Simon, argued that public education in anatomy would further the progressive improvement of society.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

By 1800, anatomy had been defined as a science—the investigation of the real—rather than an art. Anatomy could no longer tolerate humor, fancy, and ornament. Yet fantastic images of the anatomical body continued to proliferate. Cast out of medical illustration, imaginative anatomy found new homes: in academic art, where anatomy was an important part of the curriculum; in popular health, where the need to appeal to the public, and a free hand, inspired the creation of vivid, playful, and eccentric images; and in political cartoons, film, and fiction—wherever anatomical images could be made to serve.

In our time, photography, radiography, digital imaging, and computer modeling have multiplied the possibilities for manipulation and play. Artists and scientists are again exploring and re-imagining the body and investigating the boundaries between their respective disciplines. We continue to dream the anatomical body

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Anatomia per uso et intelligenza del disegno ricercata..., 1691

The association between death and anatomy continued in art anatomy, even as it waned in medical texts. Genga, a Roman anatomist, specialized in studies of classical sculptures. Errard, court painter to Louis XIV, helped found the Académie Royale de Peinture and was first Director of the Académie de France in Rome.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

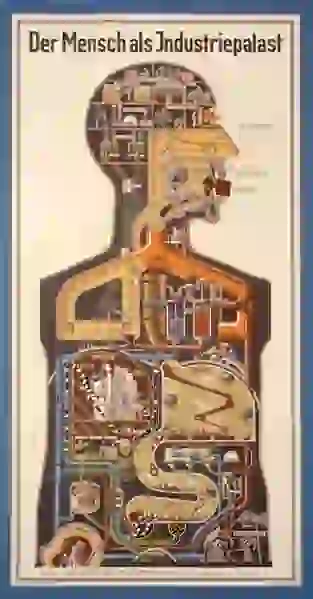

Der Mensch als Industriepalast (Man as Industrial Palace), 1926

Kahn’s visualization of the digestive and respiratory system as "industrial palace"—really a chemical plant—was conceived in a period when the German chemical industry was the world’s most advanced.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

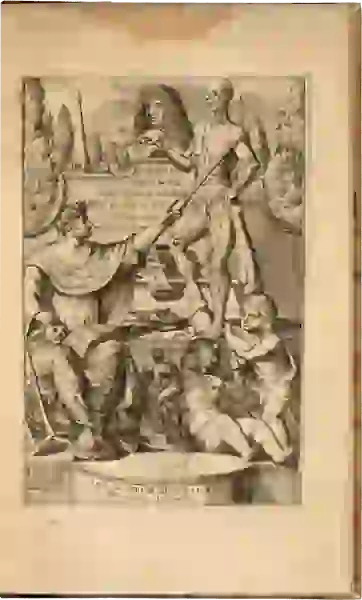

Dissection Theatres

Title pages and frontispieces functioned as a visual synopsis of the science and art of anatomy, a place where artists could playfully represent the poetics of dissection. They typically featured skeletons, cadavers, famous physicians, and mythical figures, placed in anatomical theaters and arcadian landscapes, amidst dissecting tables, bones, classical architecture, floating symbols and text. The frontispiece was the last refuge of fantasy in scientific anatomy. In the mid-1700s anatomists began to drop them, but the frontispiece continued on in art anatomies and popular scientific books.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

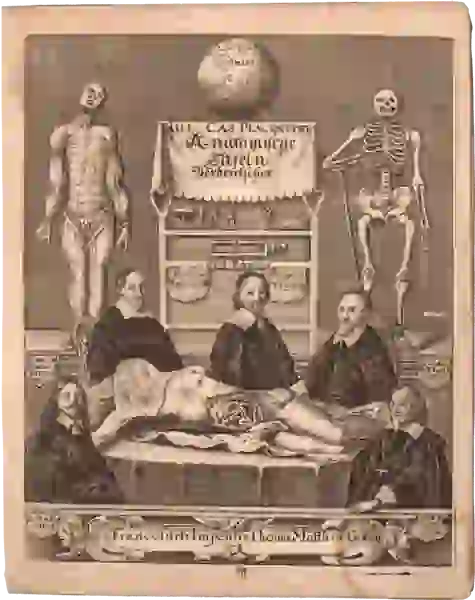

Anatomische Tafeln..., 1656

This clumsy frontispiece features five notable anatomists posed around a cadaver. In the center of the picture, the image of the Earth, with the continent of "America" visible, signifies that the anatomized body is a "New World," and dissection a voyage of discovery.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

Tabulae anatomical ligamentorum corporus humani, 1803

The dissection of a body in an arcadian or classical setting, sometimes attended by muses or iconic medical figures such as Hippocrates, was a favorite subject for the anatomical frontispieces in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative, 1837–1839

The stiffness of the figures, and self-conscious theatricality of the scene, combined with the high "finish" of the lithograph, lend it a dreamy quality that anticipates 20th-century surrealism.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

Art and Anatomy

As naturalistic styles of painting and sculpture developed, artists sought advanced knowledge of anatomy: Vesalius offered some illustrations specifically as an aid to artists. In the 17th and 18th centuries, formal art academies were founded with anatomy as a core subject in the curriculum. Professors of anatomy performed dissections for their students and sometimes published beautiful, imaginative, and monumental, books of anatomical studies that were works of art in their own right. Typically, the art anatomy used cadavers and skeletons as models for sculpture and painting. It concentrated on skeletal and muscular anatomy and omitted everything else.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

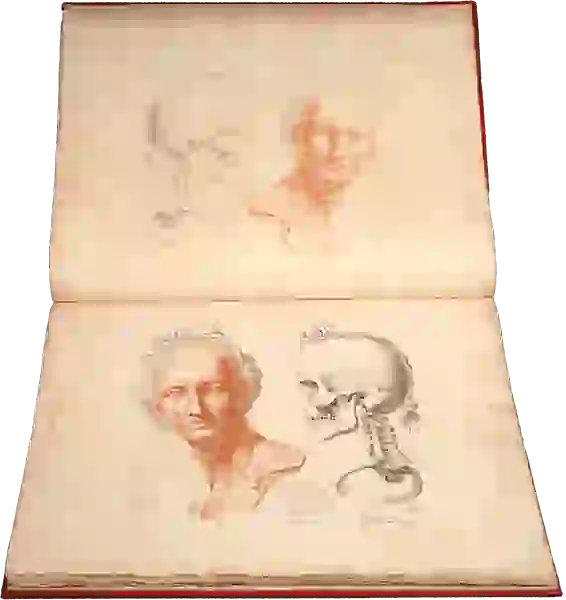

Elementi di anatomia fisiologica applicata alle belle arti figurative, 1837–39

The anatomical studies for real, imaginary, and prospective sculptures and paintings proliferated in the early and middle decades of the 19th century.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

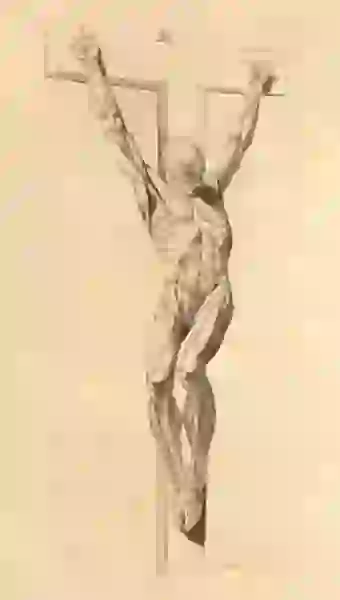

Nouveau recueil d’ostéologie et de myologie, 1779

A preoccupation with musculature was characteristic of much of art anatomy: here the striations of the muscles are emphasized to show their twisting, rope-like quality. The elevation of form over content, lends the illustration a feeling of high abstraction.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Nouveau recueil d’ostéologie et de myologie, 1779

Anatomical studies, originally used in the composition of religious and historical paintings, became a genre in their own right.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Anatomie du gladiateur combattant, applicable aux beaux arts..., 1812

A military doctor of the Napoleonic era, Salvage based his drawings on dissections of soldiers "killed in duels, in their prime." For this study of the Borghese Gladiator, an ancient Greek statue, he arranged his cadavers in the same pose as the sculpture and meticulously worked out the skeletal and muscular anatomy. Anatomical studies of important classical sculptures constituted a genre within fine art.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

The People’s Anatomy

Although allegory, metaphor, and bizarre juxtapositions were no longer featured in serious scientific texts after 1800, popular writers on medical topics continued to use them. Books and lectures on health attracted large audiences but there was much competition. Phrenologists, dietary reformers, botanical healers, homeopaths, and orthodox health advocates all vied for the public eye and ear. Arresting visual images helped popular writers explain their ideas about the structure and workings of the body.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology, Boston, 1842

Gove argued that women needed to learn human anatomy as a crucial aid to moral and intellectual improvement, a controversial point in 1842. The praying skeleton—also used in William A. Alcott’s landmark popular anatomy, The House I Live In (1837)—is copied from William Cheselden’s 1713 Anatomy of the Humane Body.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

The Composite Man as Comprehended in Fourteen Anatomical Impersonations. 2nd ed., 1901

A homeopathic practitioner, Pratt ardently recommended "orificial surgery"—operations on the mouth, nose, ears, rectum, cervix, urethra—for problems such as constipation, eczema, insanity, tuberculosis, or just for maintenance of health. His enthusiasm for surgery led to an emphasis on anatomy in writings for the public.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

The Industrial Body

In the early 20th century, Fritz Kahn (1888–1968) produced a succession of books on the inner workings of the human body, using visual metaphors drawn from industrial society—assembly lines, internal combustion engines, refineries, dynamos, telephones, etc. The body, in Kahn’s work, was "modern" and productive, a theme visually emphasized through modernist artwork. Though his books sold well, his Jewishness, and public advocacy of progressive reform, made him a target for Nazi attacks. Rescued by American agent Varian Fry, along with other prominent Jewish scientists and intellectuals, he was brought to America in 1940.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 2

Das Leben des Menschen... (The Life of Man). Vol. 2, 1926

The nervous system here is visually compared to an electronic signaling system; the brain is an office where messages are sorted.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 2

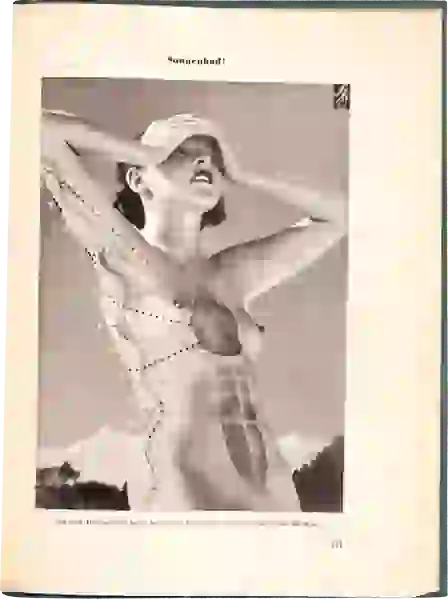

Der mensch gesund und krank, menschenkunde 1940…. Vol. 2, 1939

This manipulated photo shows the effects of sunlight on the health of the body.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

Das Leben des Menschen... (The Life of Man). Vol. 5, 1931

The physiology of vision, with the rods and cones of the pupils as receptors of light, is compared to the technology of photographic reproduction in which an image is screened and broken down into dot patterns.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Das Leben des Menschen... (The Life of Man). Vol. 5, 1931

While the interior of the body is often visualized as a landscape or terrain, here the perspective is an anatomical landscape from the inside of the nostril looking out.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 4 of 2

Das Leben des Menschen... (The Life of Man). Vol. 5, 1931

As agricultural laborers do the work of harvesting wheat, their bodies burn energy, a process symbolically represented by an internal flame.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

X-ray Visions

Wilhelm Röntgen’s 1895 discovery of the x-ray was greeted with rapturous enthusiasm, as one of the technological wonders of the age. The ability to see through the skin, into the interior of the living body, saved lives and profoundly stirred the cultural imagination. Röntgen won the first Nobel Prize in physics and the x-ray quickly became an important tool for medical researchers and clinicians. It also became a favorite subject for cartoonists and artists—and quickly found applications in shoe stores and other unlikely places.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 1

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays, 1933

The first x-ray image was the hand of Mrs. Wilhelm.

The announcement of Röntgen’s discovery, illustrated with an x-ray photograph of his wife’s hand, was hailed as one of mankind’s greatest technological accomplishments, an invention that would revolutionize every aspect of human existence.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 1

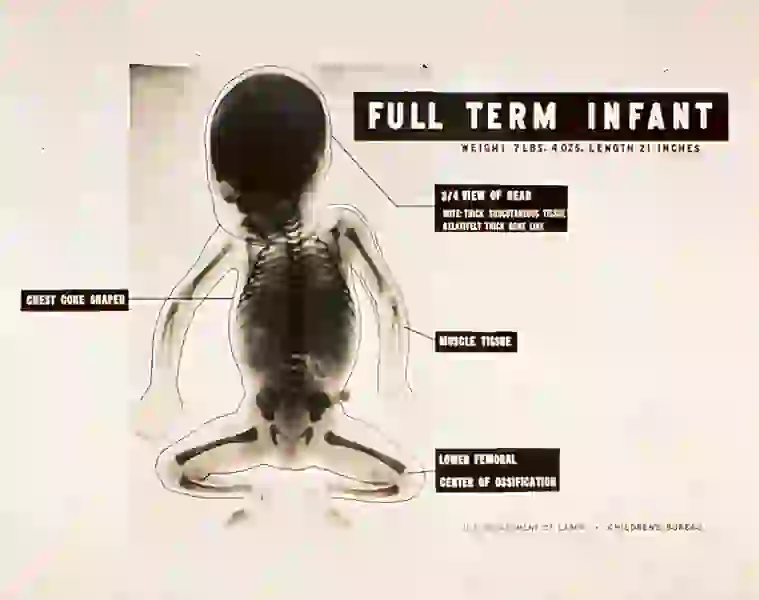

U.S. Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau. Infant Growth and Development, ca. 1943

The x-ray quickly became one of the defining devices of modern scientific medicine and was often featured in public health campaigns.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 2

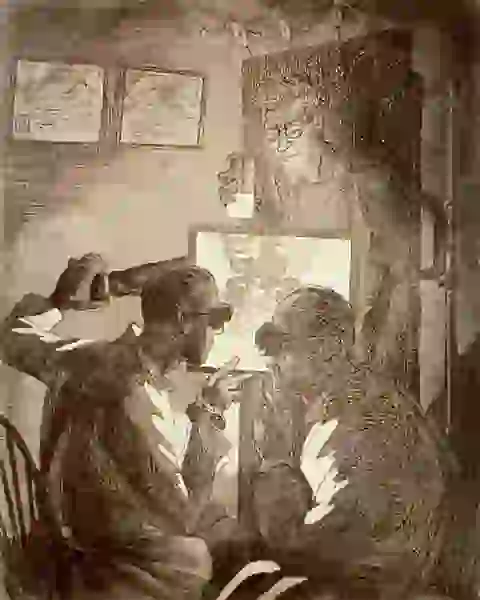

X-Rays, n.p., 1926

Sloan, a prominent exponent of the "Ashcan School," sought inspiration from everyday scenes and activities of modern life, such as the taking of x-rays, rather than landscape, nudes, and the other traditional subjects of academic art.

-

DigitalCollections

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 2

Inside/Outside: Muscle/Hand, 1994

The process of anatomy involves a prying apart of the self. The dissecting mind is divorced from the dissected body. Our identification with anatomical images always creates a mirror effect: anatomical representations are always both Self and Other.

Katherine Du Tiel makes photographs of living bodies covered with projected anatomical images—a playful exploration of our continual attempts to synthesize the two, or perhaps an ironic comment on the impossibility of synthesis.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Visionary and Visible: Dreaming Anatomy in Modernity

Visible Human Art

We have no direct access to the interior of our bodies. What goes on inside us is a mystery. Anatomical representation and imaging offer us a trace or facsimile of the inner self: a mirror image that is an incitement to dream.

Anatomists first began to take cross sections from frozen cadavers in the early 1800s. They found that slices could translate the three-dimensional complexity of organic structures into flat, easy-to-read specimens, which then could be preserved or drawn by an artist. In 1989, the National Library of Medicine embarked on a plan to use frozen cross sections to make a comprehensive digitized "library" of the human body: the Visible Human Project.

Two bodies, acquired through donations, met bioethical standards of informed consent: a 39-year-old convict executed in Texas by lethal injection; and a 59-year-old Maryland housewife who died of cardiovascular disease. Scientists scanned the cadavers, using CT (computerized tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). The corpses, deep-frozen in blue gelatin, were then milled to remove thin cross sections of tissue, from head to toe. As each layer was exposed, the surface was digitally photographed, creating data that could be reassembled, navigated, and manipulated with computer software.

The monumental pieces presented here were part of a physical display at the National Library of Medicine during October 9, 2002–July 31, 2003. These works by Alexander Tsiaras, Carolyn Henne, Jussi Ängeslevä, and two Visible Human Plexi-Books—originally commissioned by the San Francisco Exploratorium—use data from the National Library of Medicine's Visible Human dataset. By virtue of their scale, they model a direct one-to-one correspondence between representation and reality: the anatomical image looms as large as the living, breathing self.

Close Menu ITEM 0 of 1

Body Scanner, 2002

Finnish designer Jussi Ängeslevä’s interactive installation allows a visitor to track segments of the Visible Human data set against segments of his or her own body. Despite the discrepancy between displayed image and user—the lack of heartbeat and other internal movements, etc.—the immediacy of the interaction creates the illusion of reality. Visitors often assume they are seeing themselves. The experiential "realness" of Body Scanner shows how easily anatomical imagery gets translated into body image.

-

Transcript

A man steps onto a round platform and lifts a metal ring up from his feet to his head. As he does so cross section images of a body from the visible human project corresponding to the height of the ring display on a monitor in front of him, giving the illusion that the images are of his own body. He moves the ring all the way to his head. The view of the camera pulls back to show the installation in the Dream Anatomy Exhibition surrounded by exhibition graphics and display cases holding books. The video has no narration, but slow meditative music accompanies the action.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 1 of 1

Suspended Self Portrait, 2002

Suspended Self Portrait, an interactive sculpture installation, consists of 89 vinyl sheets painted with cross-section images derived from the Visible Human dataset. To determine the cross sections, artist Carolyn Henne made a mold of herself and sliced it. Then, she painted a corresponding Visible Human cross-section—organs, muscles, fat, bone—on each sheet. From a distance, the body seems to float in three dimensions. Closer up, visitors can touch the sheets to make the organs appear to assemble and dissolve. Blowing on the sheets or running one’s fingers along the edges causes the figure to subtly move as if floating or breathing. Suspended Self Portrait helps us to visualize an inner self often left unclaimed as we try to maintain our profile in the world.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 2 of 1

Visible Human as Atlas holding up the Earth, 2002

In 17th-century Europe, readers were often encouraged to think of the anatomical body in geographical terms, as "a little world," or as a microcosm. "Whatsoever is in the universal world is also in man," and made visible through anatomy, argued Nicholas Culpepper in 1654. This animated laser hologram, by artist/scientist/journalist Alexander Tsiaras, updates the metaphor by refiguring the Visible Human as Atlas holding up the Earth. The piece is based on one of the most celebrated statues of antiquity, the Farnese Atlas (ca. 200 A.D., currently in the National Archeological Museum, Naples).

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Close Menu ITEM 3 of 1

The Visible Human Plexi-Books, 2000

Originally created for the San Francisco Exploratorium’s Revealing Bodies exhibition, these two pieces representing the male and female Visible Human, are now the largest "books" in the National Library of Medicine’s collection. By virtue of their monumental scale, they allow viewers to enter into, and identify with, the Visible Humans, and remind us of their humanity. At the same time, the scale of the figures, and their "meatiness," may also provoke feelings of estrangement from our customary identification with anatomical imagery.

-

EnlargeImage

-

Copy Link

Copied

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Egestas purus viverra accumsan in nisl. Vulputate dignissim suspendisse in est ante in nibh mauris cursus. Consectetur purus ut faucibus pulvinar elementum integer enim neque volutpat. Massa sapien faucibus et molestie ac feugiat sed lectus vestibulum. Id diam vel quam elementum pulvinar etiam. Tristique sollicitudin nibh sit amet commodo nulla facilisi. Odio euismod lacinia at quis risus sed vulputate odio.

-

DigitalCollections

-

Transcript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

-

EnlargeImage

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link