In 1981, a new disease appeared in the United States.

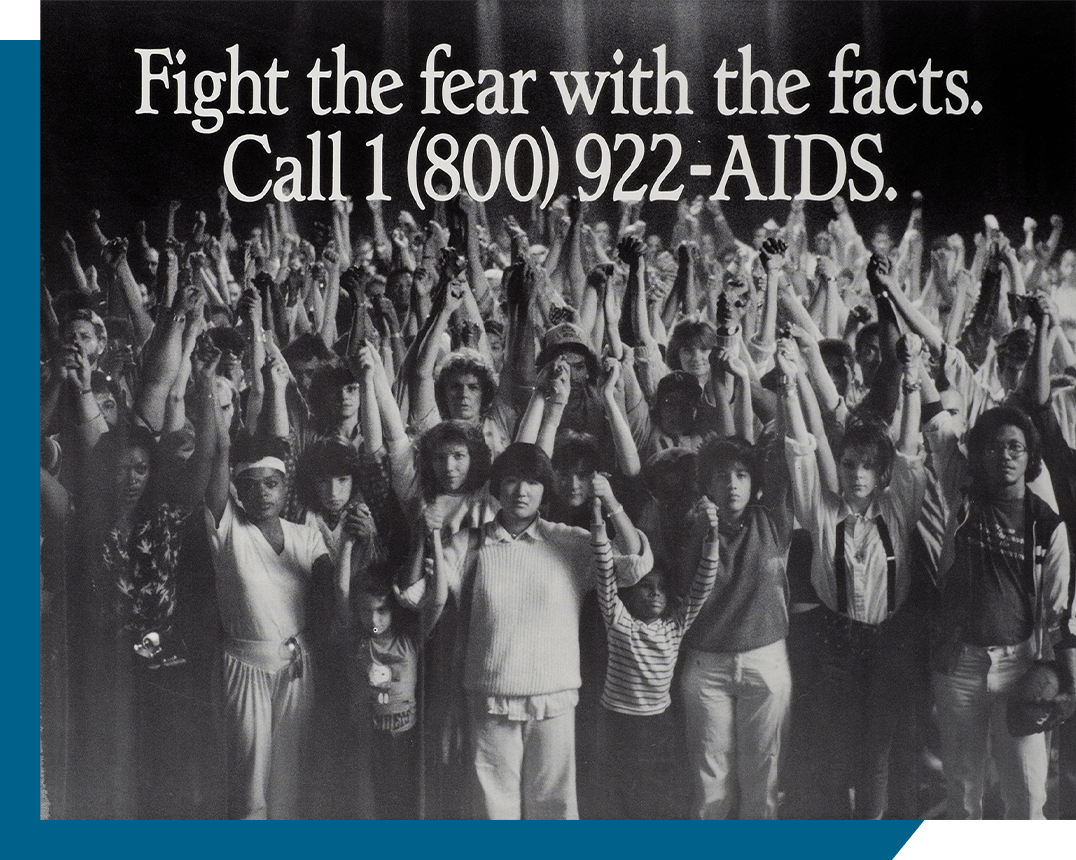

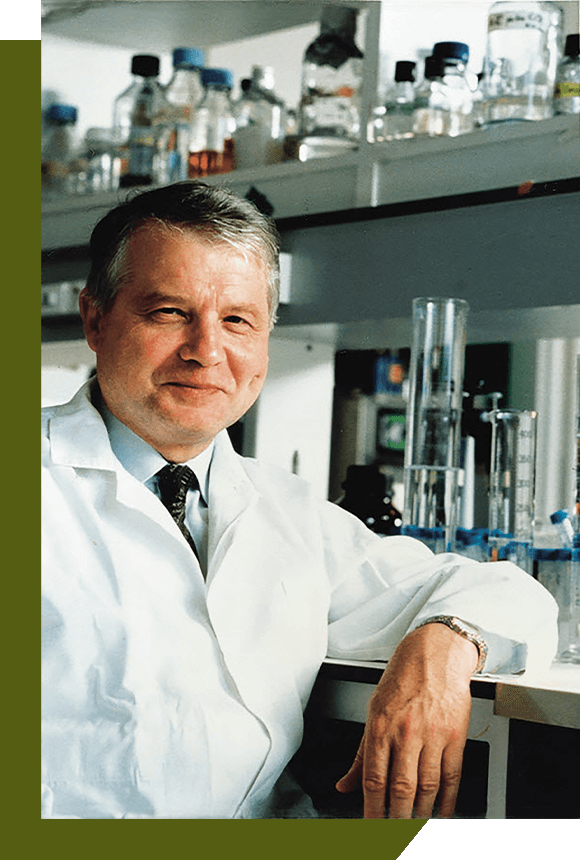

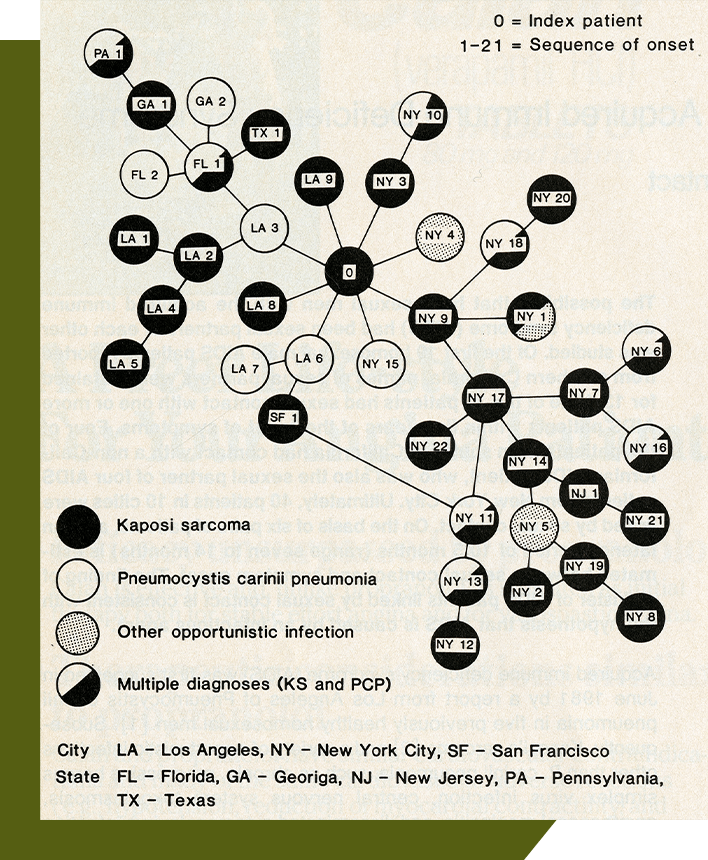

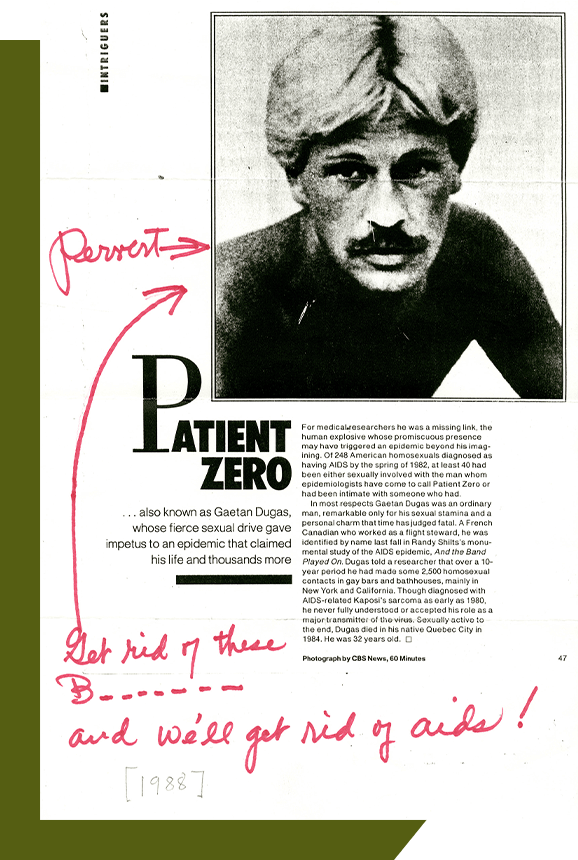

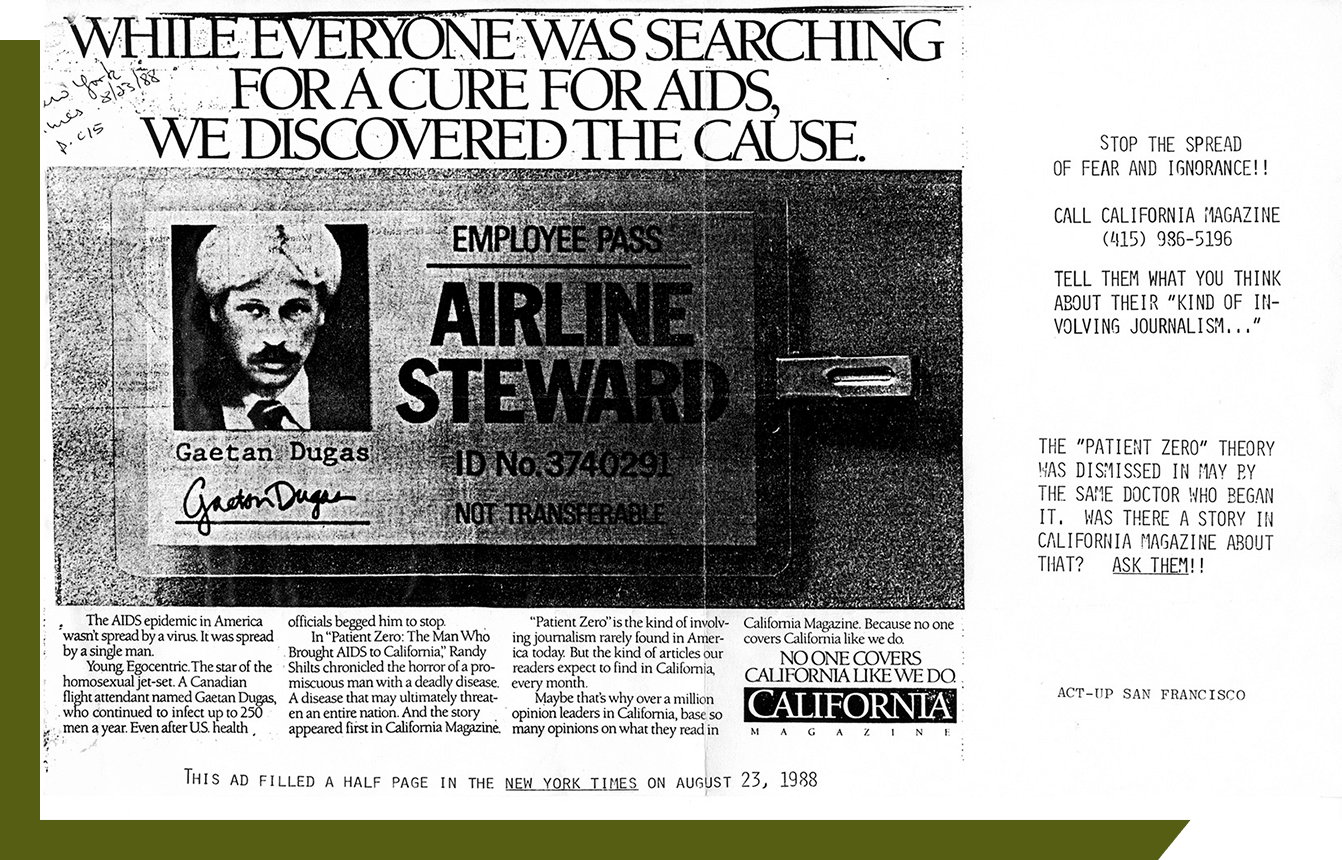

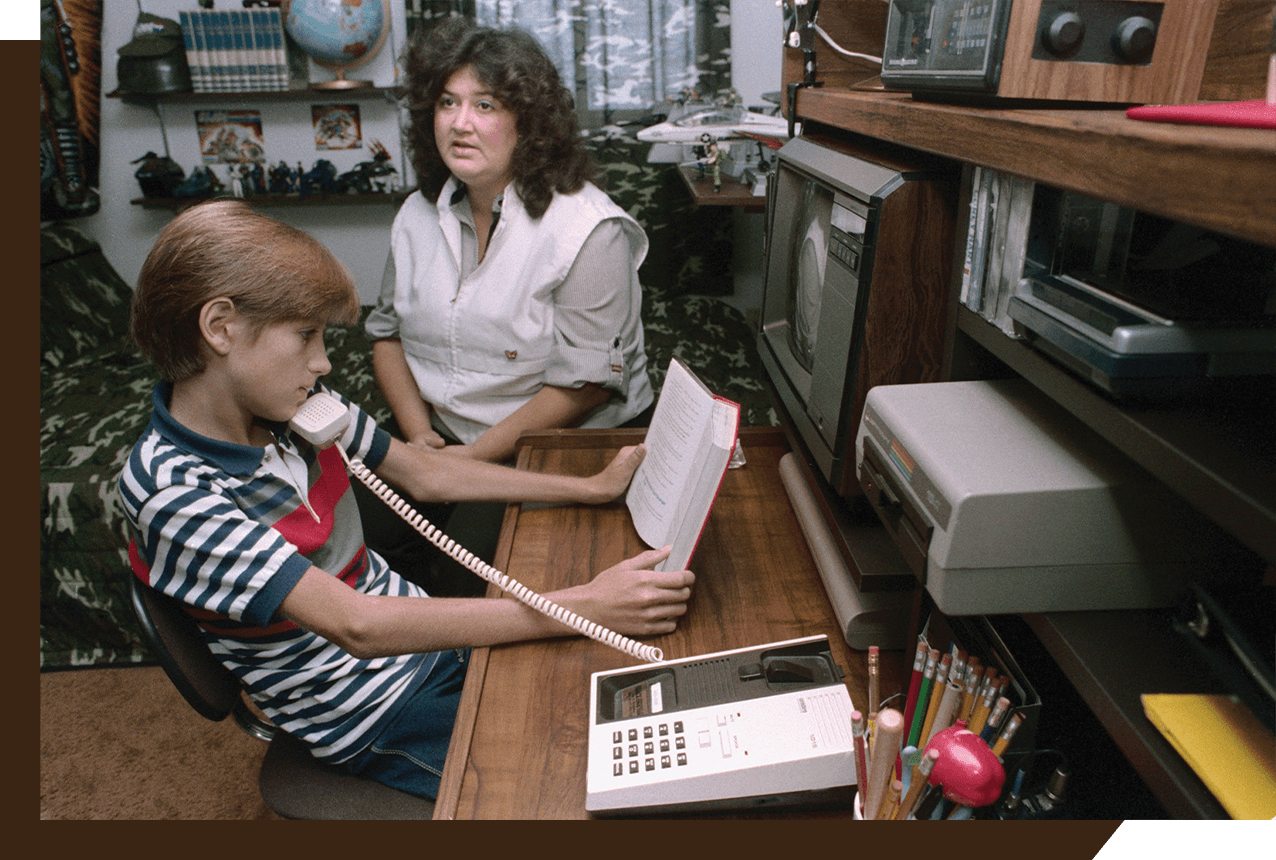

As it spread, fear and confusion pervaded the country. The infectious “rare cancer” bewildered researchers and bred suspicion, but worry was not the same for everyone. Many feared contact with those who were ill. Others, particularly but not exclusively gay men, feared for their lives and the lives of loved ones.

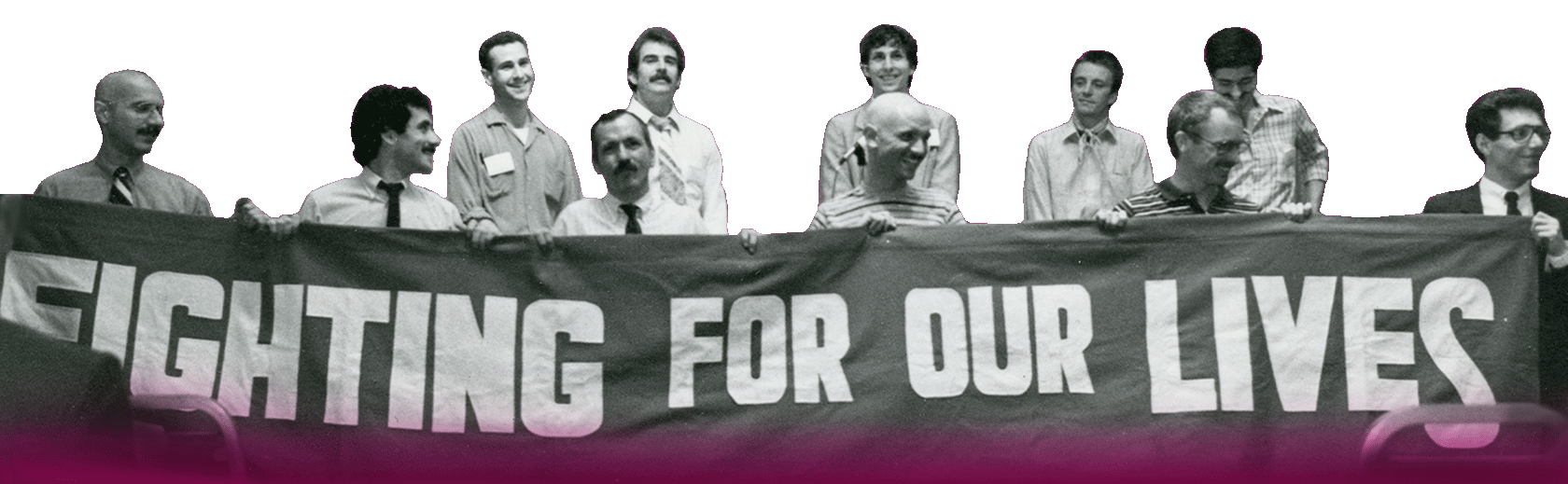

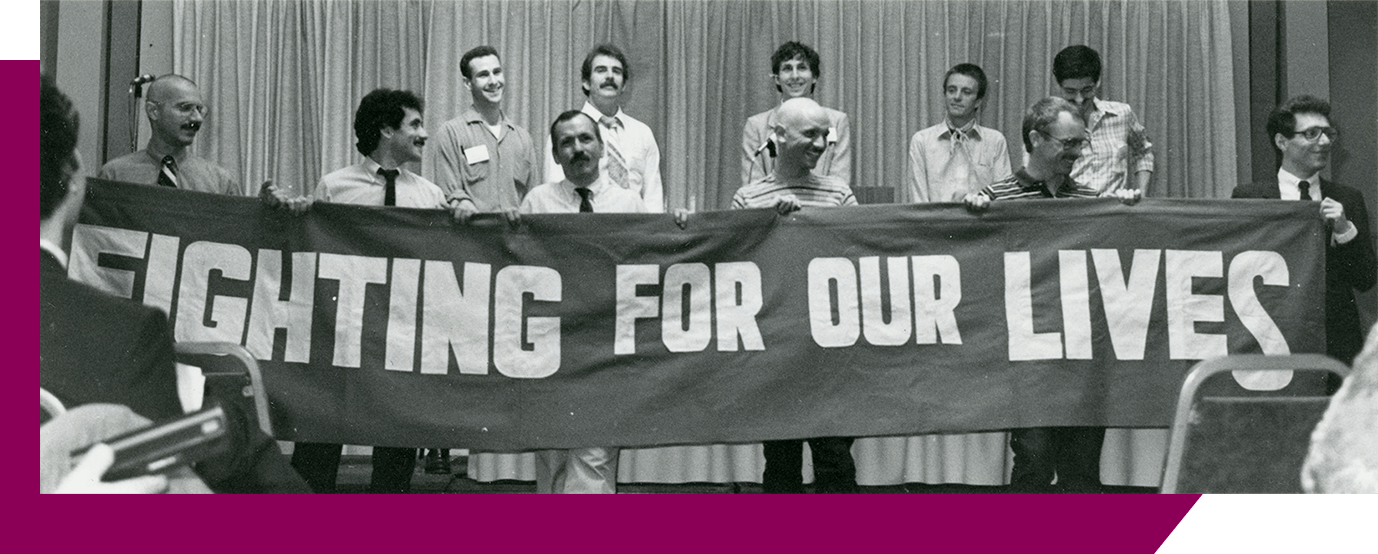

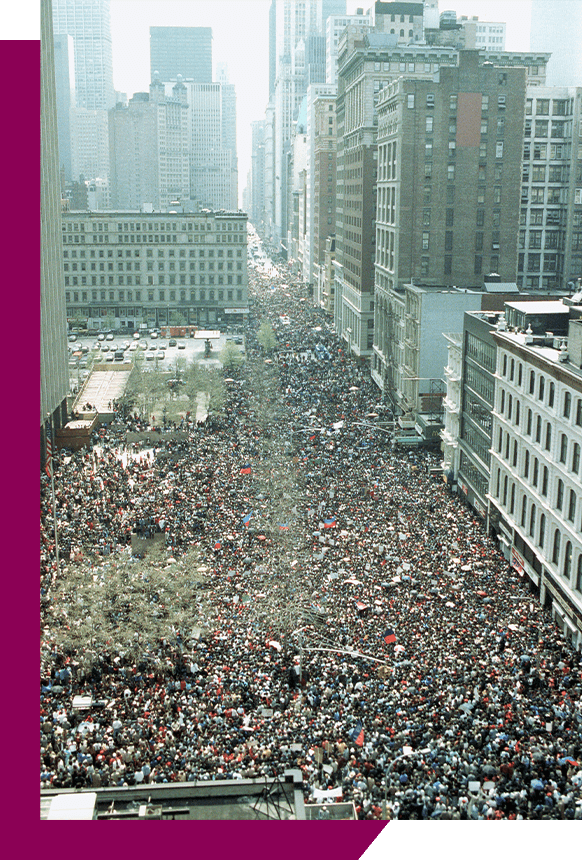

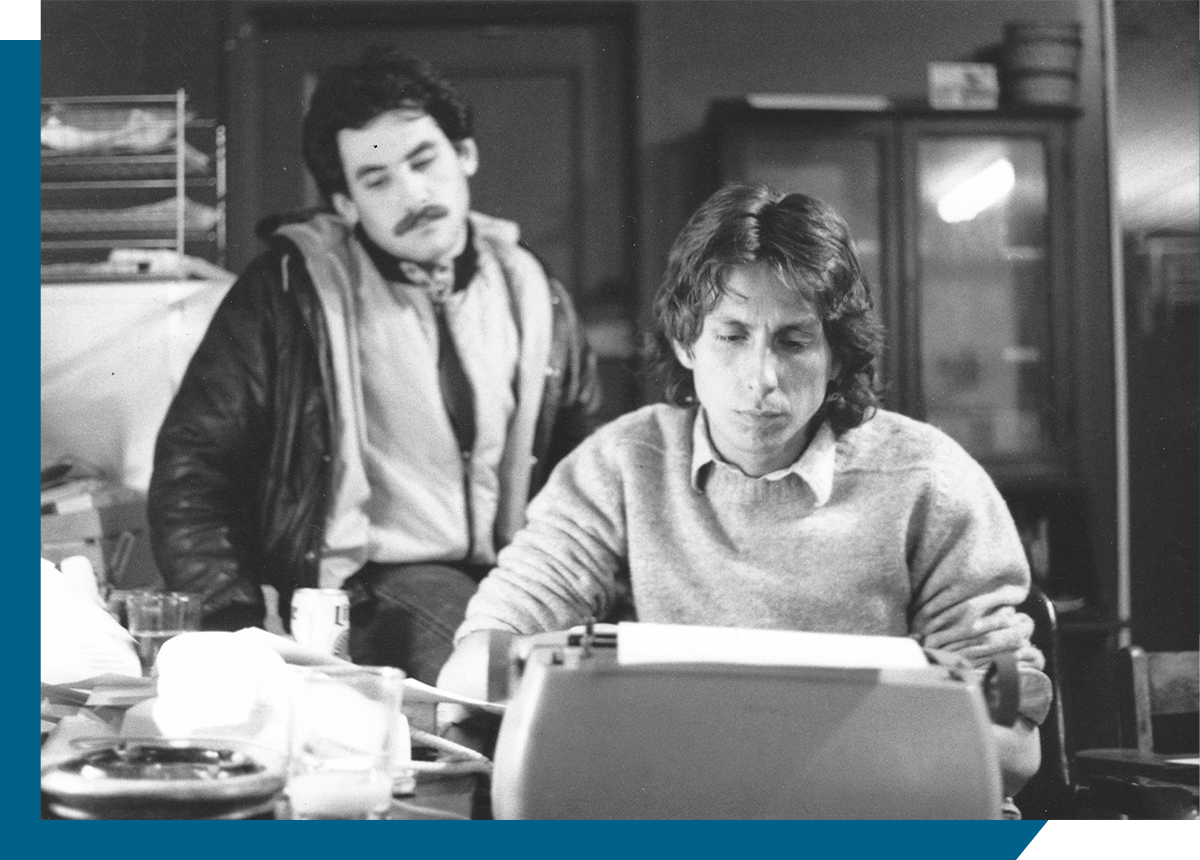

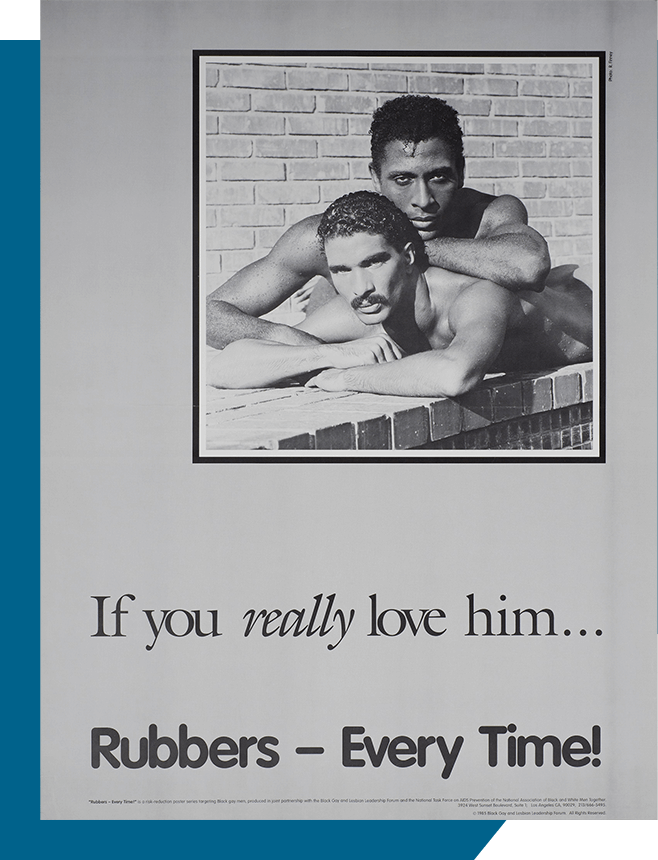

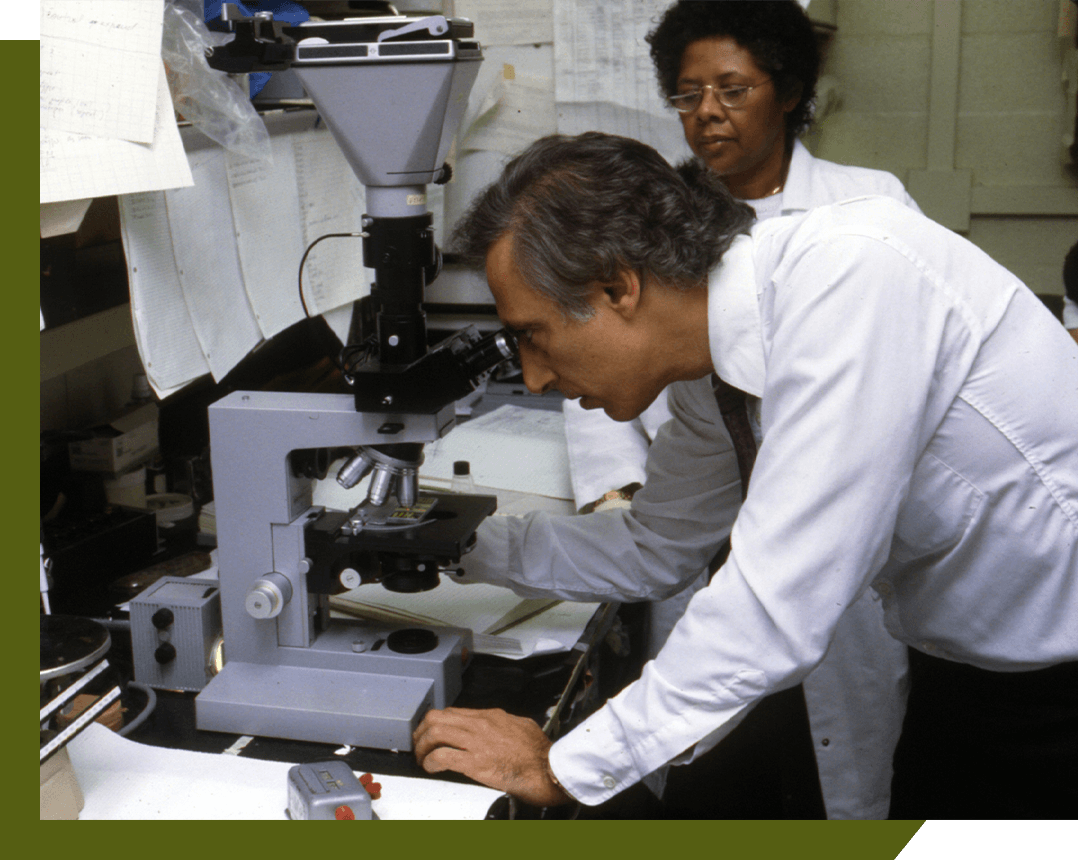

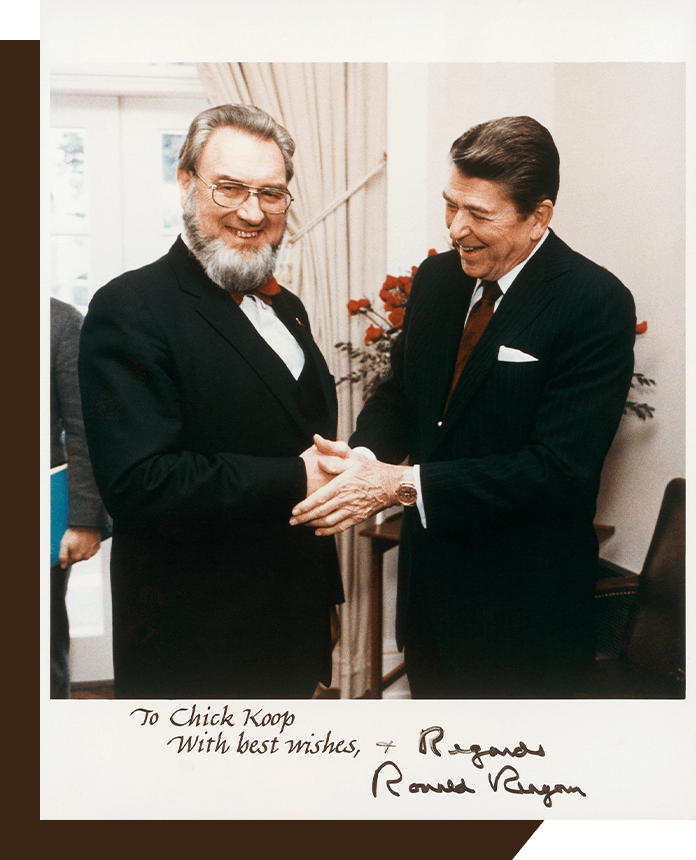

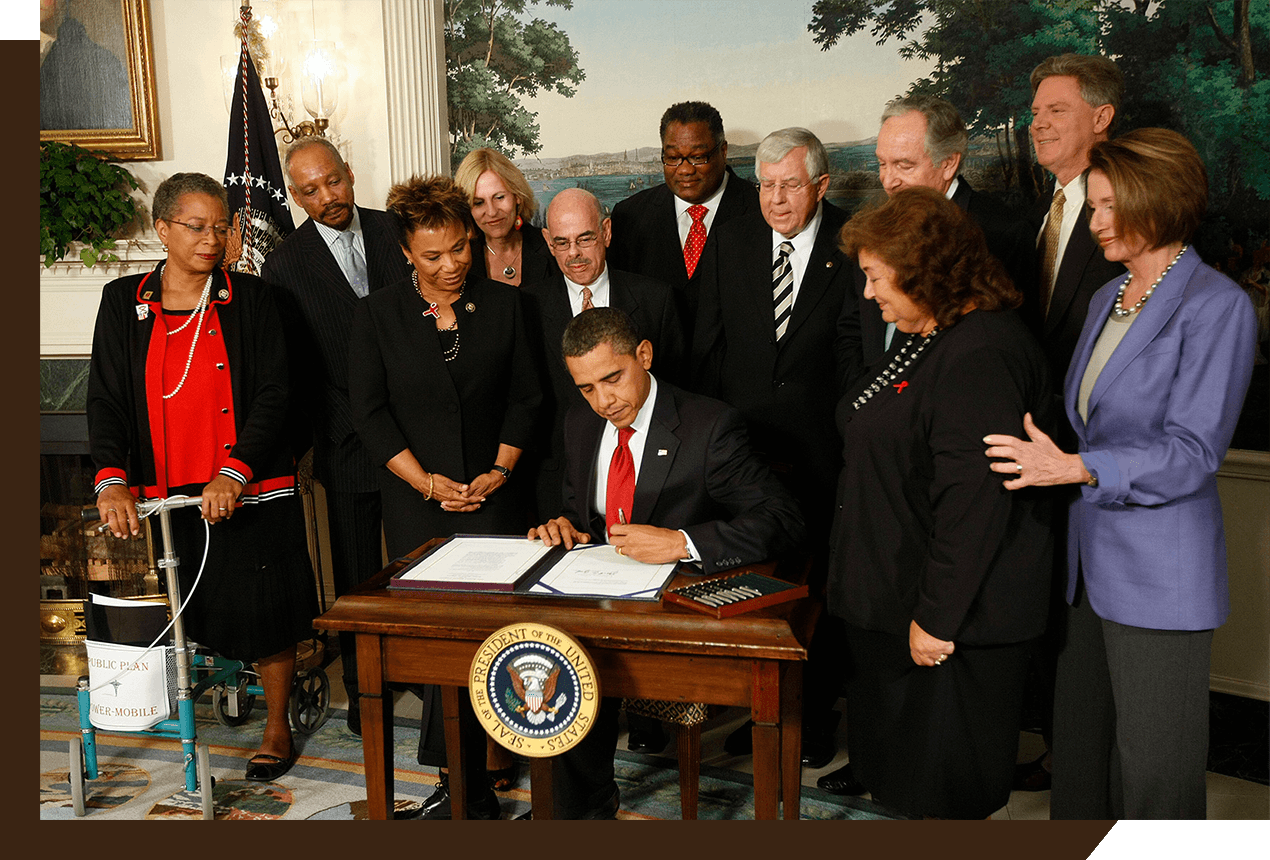

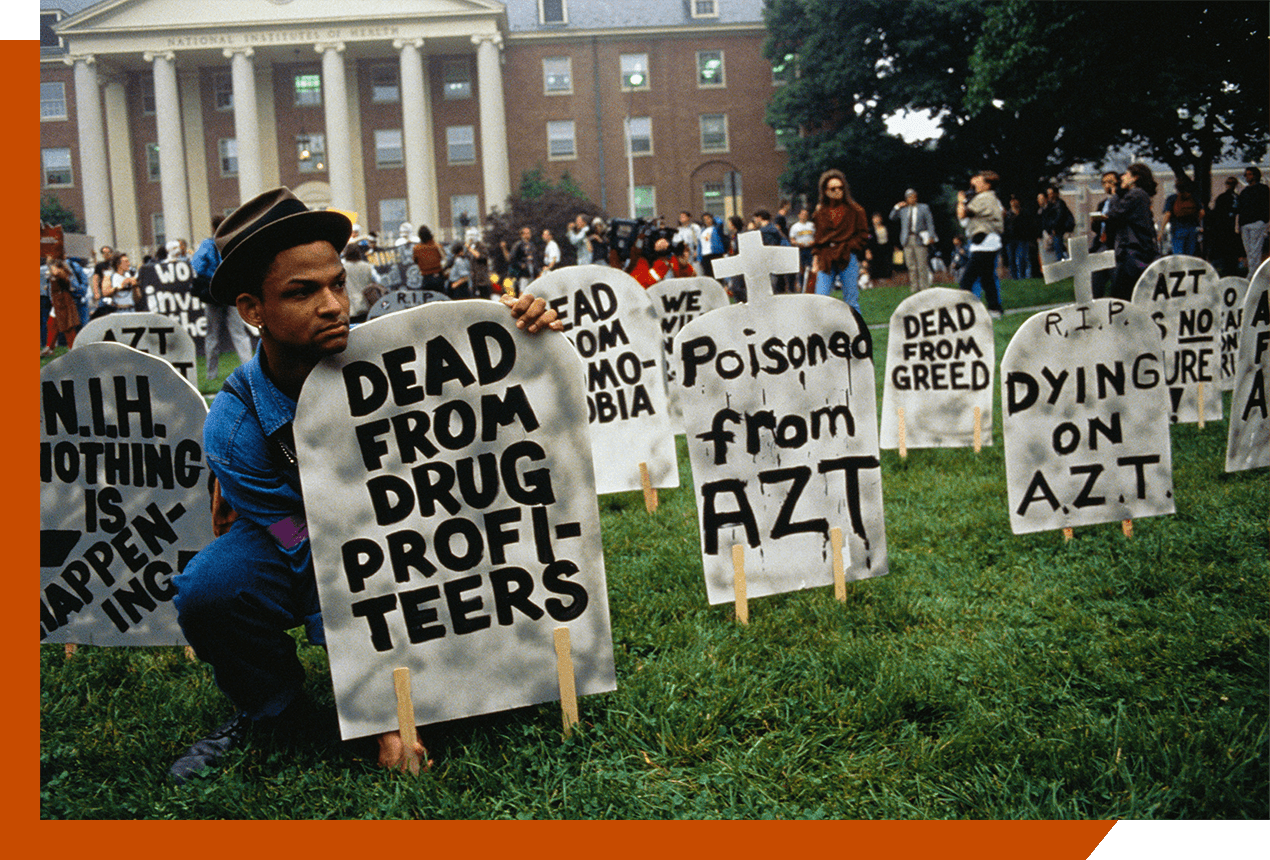

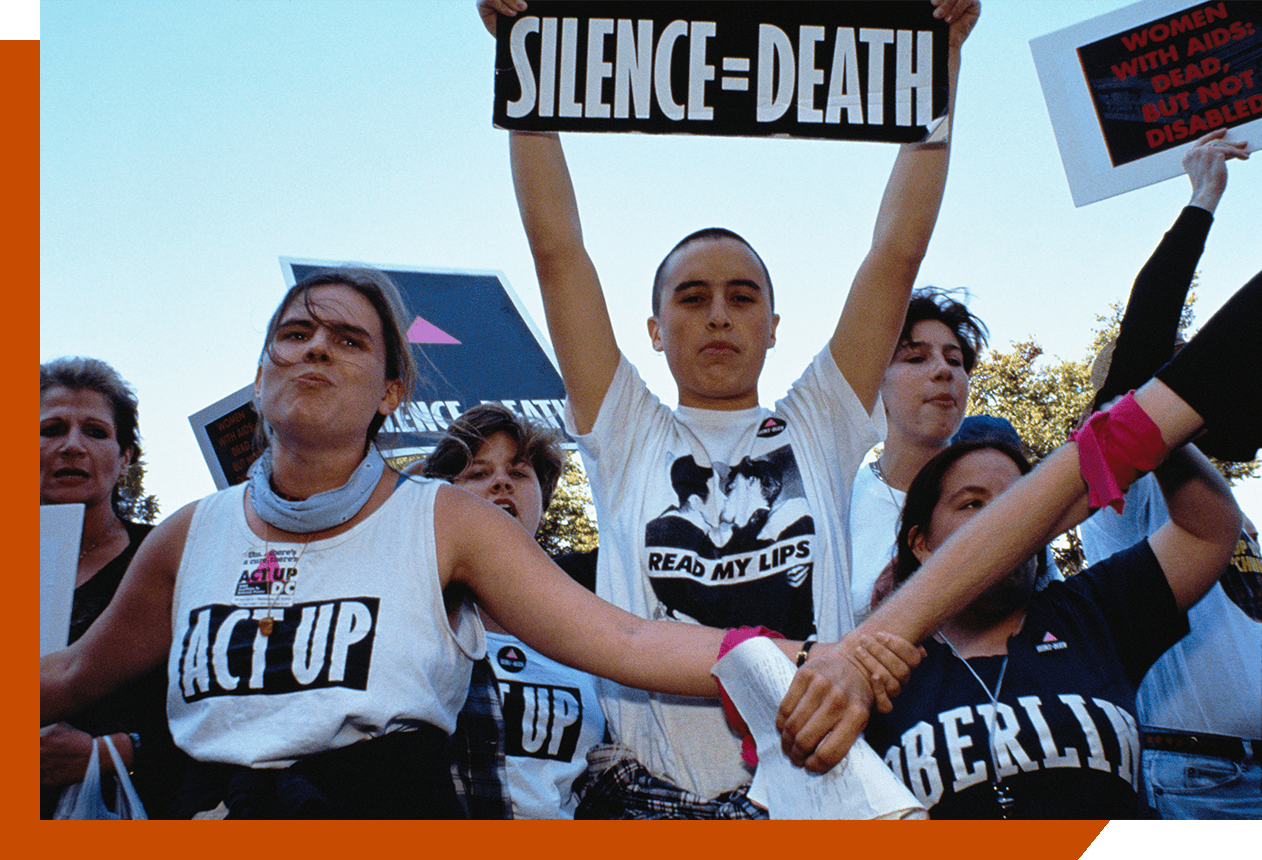

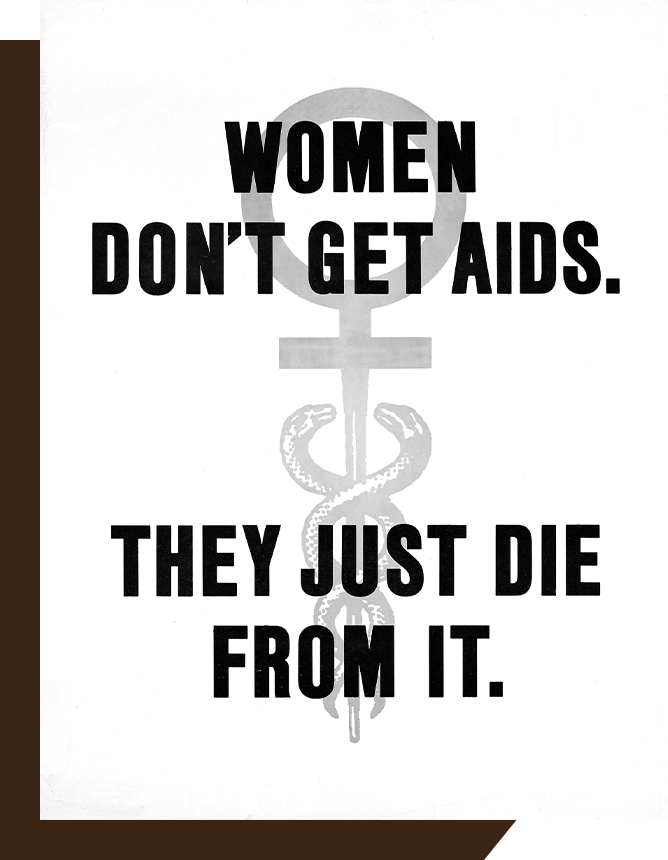

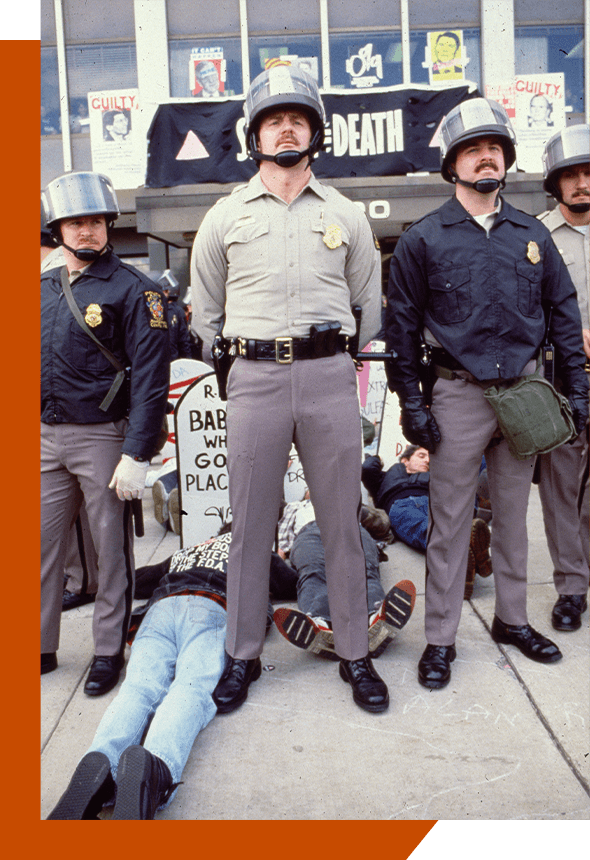

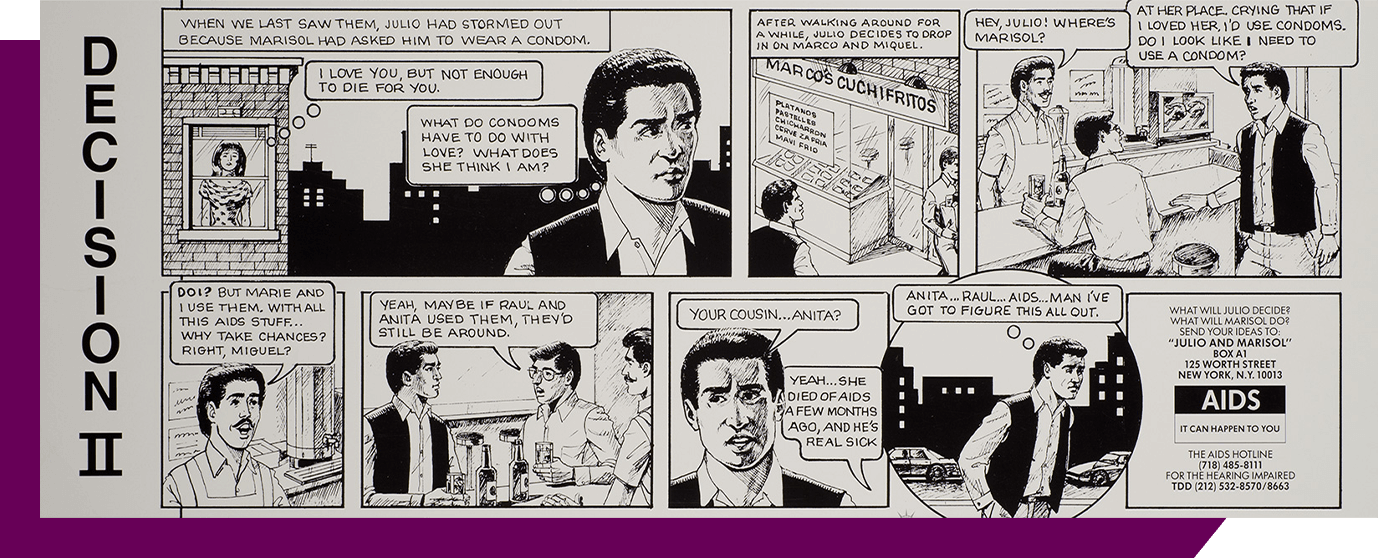

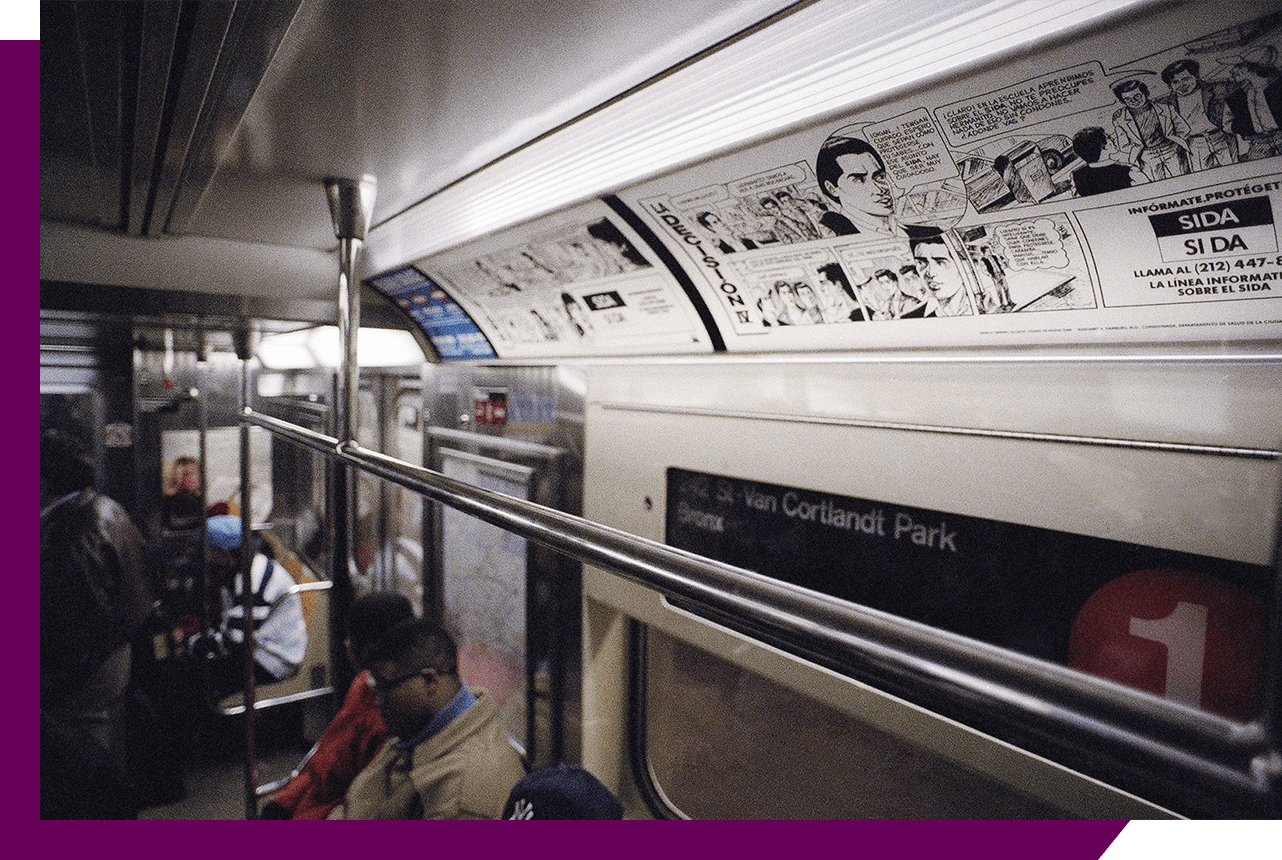

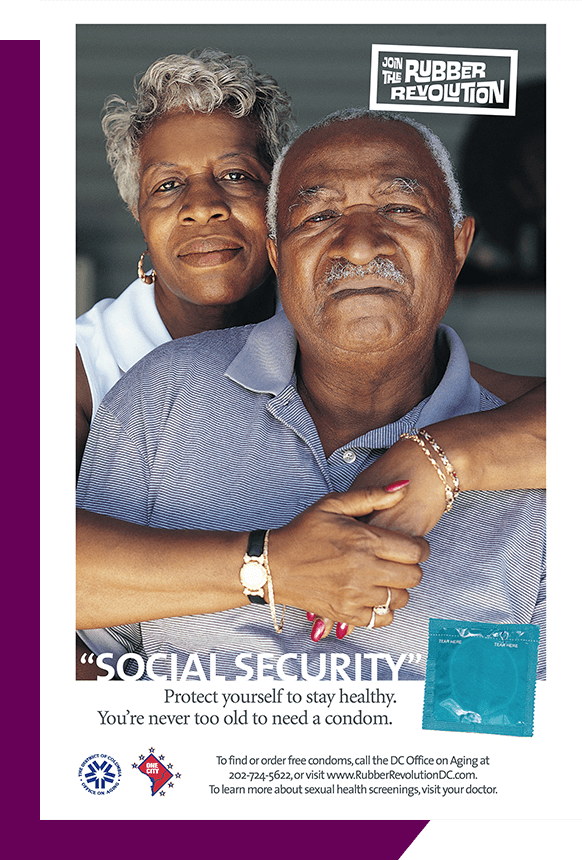

Reactions to the disease, soon named AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), varied. Early responders cared for the sick, fought homophobia, and promoted new practices to keep people healthy. Scientists and public health officials struggled to understand the disease and how it spread. Politicians remained largely silent until the epidemic became too big to ignore. Activists demanded that people with AIDS be part of the solution.

The title Surviving and Thriving comes from a book written in 1987 by and for people with AIDS that insisted people could live with AIDS, not just die from it. This exhibition presents their stories alongside those of others involved in the national AIDS crisis. Listen to them and consider the ever-changing relationship between science and society.