Suspected ear infections are one of the most common reasons parents take their children to the health care provider. The most common type of ear infection is called otitis media. It is caused by swelling and infection of the middle ear. The middle ear is located just behind the eardrum.

An acute ear infection starts over a short period and is painful. Ear infections that last a long time or come and go are called chronic ear infections.

Causes

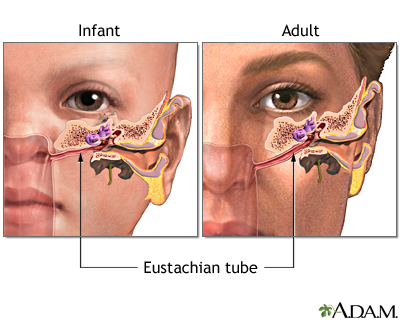

The eustachian tube runs from the middle of each ear to the back of the throat. Normally, this tube drains fluid that is made in the middle ear. If this tube gets blocked, fluid can build up. This can lead to infection.

- Ear infections are common in infants and children because their eustachian tubes are easily clogged.

- Ear infections can also occur in adults, although they are less common than in children.

Anything that causes the eustachian tubes to become swollen or blocked leads to more fluid buildup in the middle ear behind the eardrum. Some causes are:

- Allergies

- Colds and sinus infections

- Excess mucus and saliva produced during teething

- Infected or overgrown adenoids (lymph tissue in the upper part of the throat)

- Tobacco smoke

Ear infections are also more likely in children who spend a lot of time drinking from a sippy cup or bottle while lying on their back. Milk may enter the eustachian tube, which may increase the risk of an ear infection. Getting water in the ears will not cause an acute ear infection unless the eardrum has a hole in it.

Other risk factors for acute ear infections include:

- Attending day care (especially centers with more than 6 children)

- Changes in altitude or climate

- Cold climate

- Exposure to smoke

- Family history of ear infections

- Not being breastfed

- Pacifier use

- Recent ear infection

- Recent illness of any type (because illness lowers the body's resistance to infection)

- Birth defect, leading to deficiency in eustachian tube function

Symptoms

In infants, often the main sign of an ear infection is acting irritable or crying that cannot be soothed. Many infants and children with an acute ear infection have a fever or trouble sleeping. Tugging on the ear is not always a sign that the child has an ear infection.

Symptoms of an acute ear infection in older children or adults include:

- Ear pain

- Fullness in the ear

- Feeling of general illness

- Nasal congestion

- Cough

- Lethargy

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Hearing loss in the affected ear

- Drainage of fluid from the ear

- Loss of appetite

The ear infection may start shortly after a cold. Sudden drainage of yellow or green fluid from the ear may mean the eardrum has ruptured.

All acute ear infections involve fluid behind the eardrum. At home, you can use an electronic ear monitor to check for this fluid. You can buy this device at a drugstore. You still need to see a provider to confirm an ear infection.

Exams and Tests

Your provider will take your medical history and ask about symptoms.

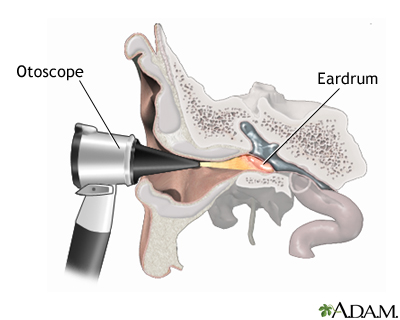

Your provider will look inside the ears using an instrument called an otoscope. This exam may show:

- Areas of marked redness

- Bulging of the tympanic membrane

- Discharge from the ear

- Air bubbles or fluid behind the eardrum

- A hole (perforation) in the eardrum

Your provider might recommend a hearing test if the person has a history of ear infections.

Treatment

Some ear infections clear on their own without antibiotics. Treating the pain and allowing the body time to heal itself is often all that is needed:

- Apply a warm cloth or warm water bottle to the affected ear.

- Use over-the-counter pain relief drops for ears. Or, ask your provider about prescription eardrops to relieve pain.

- Take over-the-counter medicines such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen for pain or fever. Do not give aspirin to children.

All children younger than 6 months with a fever or symptoms of an ear infection should see a provider. Children who are older than 6 months may be watched at home if they do not have:

- A fever higher than 102°F (38.9°C)

- More severe pain or other symptoms

- Other medical problems

If there is no improvement or if symptoms get worse, schedule an appointment with your provider to determine whether antibiotics are needed.

ANTIBIOTICS

A virus or bacteria can cause ear infections. Antibiotics will not help an infection that is caused by a virus. Most providers don't prescribe antibiotics for every ear infection. However, all children younger than 6 months with an ear infection are treated with antibiotics.

Your provider is more likely to prescribe antibiotics if your child:

- Is under age 2 years

- Has a fever

- Appears sick

- Does not improve in 24 to 48 hours

If antibiotics are prescribed, it is important to take them as directed and to take all of the medicines. Do not stop the medicine when symptoms go away. If the antibiotics do not seem to be working within 48 to 72 hours, contact your provider. You may need to switch to a different antibiotic.

Side effects of antibiotics may include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Serious allergic reactions are rare, but may also occur.

Some children have repeat ear infections that seem to go away between episodes. They may receive a smaller, daily dose of antibiotics to prevent new infections.

SURGERY

If an infection does not go away with the usual medical treatment, or if a child has many ear infections over a short period of time, the provider may recommend ear tubes:

- If a child more than 6 months old has had 3 or more ear infections within 6 months or more than 4 ear infections within a 12-month period

- If a child less than 6 months old has had 2 ear infections in a 6- to 12-month period or 3 episodes in 24 months

- If the infection does not go away with medical treatment

In this procedure, a tiny tube is inserted into the eardrum, keeping open a small hole that allows air to get in so fluids can drain more easily (myringotomy).

The tubes often eventually fall out by themselves. Those that don't fall out may be removed in your provider's office.

If the adenoids are enlarged, removing them with surgery may be considered if ear infections continue to occur. Removing tonsils does not seem to help prevent ear infections.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Most often, an ear infection is a minor problem that gets better. Ear infections can be treated, but they may occur again in the future.

Most children will have slight short-term hearing loss during and right after an ear infection. This is due to fluid in the ear. Fluid can stay behind the eardrum for weeks or even months after the infection has cleared.

Speech or language delay is uncommon. It may occur in a child who has lasting hearing loss from many repeated ear infections.

Possible Complications

In rare cases, a more serious infection may develop, such as:

- Tearing of the eardrum

- Spreading of infection to nearby tissues, such as infection of the bones behind the ear (mastoiditis) or infection of the brain membrane (meningitis)

- Chronic otitis media

- Collection of pus in or around the brain (abscess)

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if:

- You have swelling behind the ear.

- Your symptoms get worse, even with treatment.

- You have a high fever or severe pain.

- Severe pain suddenly stops, which may indicate a ruptured eardrum.

- New symptoms appear, especially severe headache, dizziness, swelling around the ear, or twitching of the face muscles.

Let your provider know right away if a child younger than 6 months has a fever, even if the child doesn't have other symptoms.

Prevention

You can reduce your child's risk of ear infections with the following measures:

- Wash your hands and your child's hands and toys to decrease the chance of getting a cold.

- If possible, choose a day care that has 6 or fewer children. This can reduce your child's chances of getting a cold or other infection.

- Avoid using pacifiers.

- Breastfeed your baby.

- Avoid bottle feeding your child when they are lying down.

- Avoid smoking.

- Make sure your child's immunizations are up to date. The pneumococcal vaccine prevents infections from the bacteria that most commonly cause acute ear infections and many respiratory infections.

Alternative Names

Otitis media - acute; Infection - inner ear; Middle ear infection - acute

References

Haddad J, Dodhia SN. General considerations and evaluation of the ear. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 654.

Kerschner JE, Preciado D. Otitis media. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 658.

Pelton SI. Otitis externa, otitis media, and mastoiditis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 61.

Ranakusuma RW, Pitoyo Y, Safitri ED, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;15;3(3):CD012289. PMID: 29543327 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29543327/.

Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis media with effusion (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(1 Suppl):S1-S41. PMID: 26832942 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26832942/.

Rosenfeld RM, Tunkel DE, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children (update).Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(1_suppl):S1-S55. PMID: 35138954 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35138954/.

Schilder AGM, Rosenfeld RM, Venekamp RP. Acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion. In: Flint PW, Francis HW, Haughey BH, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 199.

Test Your Knowledge

Review Date 1/24/2023

Updated by: Neil K. Kaneshiro, MD, MHA, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Internal review and update on 02/03/2024 by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.