NARRATOR:

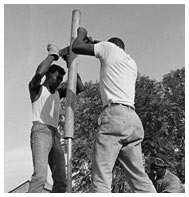

Our story begins with the declaration of Alma-Ata, which defined health as a human right, based on the importance of everyday needs, like clean water and a safe place to live, for a healthy life. Alma-Ata, now known as Almaty, is a city in Kazakhstan.In September, 1978, representatives from 134 countries and 67 organizations met there to discuss how to improve global healthcare ... the largest gathering of its kind in history. Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist Laurie Garrett writes on global health issues.

LAURIE GARRETT:

...one of the key features of Alma-Ata was to consider health part of well-being; to take it beyond just the absence of disease to the presence of well-being. So you can't have well-being if you're living next to a stream that's full of parasitic diseases and your children drink that water and die of dysentery. You can't have well-being if you have no housing, no place to live.

NARRATOR:

Not all of the declaration's goals have been realized, but that does not mean that the meeting at Alma-Ata failed, says Dr. Paul Farmer, who founded Partners in Health, an international health and social justice organization.

PAUL FARMER:

The great thing was that everybody did come together and say, "Look, everybody in the world deserves access to basic health care as a right." It serves as a model of ... what can be agreed upon. And ... then comes the work of civil society, of community organizations, of the movement ... to transform these from documents into reality.

throughout the online exhibition or download individual tour stops using the links below.

throughout the online exhibition or download individual tour stops using the links below.