Exhibition Gallery

Exhibition Gallery

Celebrating America's Women Physicians

Women have always been healers. As mothers and grandmothers, women have always nursed the sick in their homes. As midwives, wise women, and curanderas, women have always cared for people in their communities. Yet, when medicine became established as a formal profession in Europe and America, women were shut out.

Women waged a long battle to gain access to medical education and hospital training. Since then, they have overcome prejudices and discrimination to create and broaden opportunities within the profession. Gradually, women from diverse backgrounds have carved out successful careers in every aspect of medicine.

Changing the Face of Medicine introduces some of the many extraordinary and fascinating women who have studied and practiced medicine.

This 2003 exhibition honors the lives and achievements in medicine. Women physicians have excelled in many diverse medical careers. Some have advanced the field of surgery by developing innovative procedures. Some have won the Nobel prize. Others have brought new attention to the health and well-being of children. Many have reemphasized the art of healing and the roles of culture and spirituality in medicine.

Celebrating America's Women Physicians

Women have always been healers. As mothers and grandmothers, women have always nursed the sick in their homes. As midwives, wise women, and curanderas, women have always cared for people in their communities. Yet, when medicine became established as a formal profession in Europe and America, women were shut out.

Women waged a long battle to gain access to medical education and hospital training. Since then, they have overcome prejudices and discrimination to create and broaden opportunities within the profession. Gradually, women from diverse backgrounds have carved out successful careers in every aspect of medicine.

Changing the Face of Medicine introduces some of the many extraordinary and fascinating women who have studied and practiced medicine.

This 2003 exhibition honors the lives and achievements in medicine. Women physicians have excelled in many diverse medical careers. Some have advanced the field of surgery by developing innovative procedures. Some have won the Nobel prize. Others have brought new attention to the health and well-being of children. Many have reemphasized the art of healing and the roles of culture and spirituality in medicine.

Dr. Tenley E. Albright

Dr. Tenley Albright became the first American woman to win an Olympic gold medal in figure skating before breaking boundaries in the field of surgery.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Albright.

Dr. Mary Ellen Avery

Dr. Mary Ellen Avery helped discover the cause of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in premature babies. Additionally, she trained and advocated for young physicians in a long career in academic medicine.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Avery.

Dr. Nancy E. Jasso

Dr. Nancy Jasso is one of the founding physicians of a laser tattoo–removal project for the San Fernando Valley Violence Prevention Coalition, which serves people who leave gangs.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Jasso.

Dr. Vivian W. Pinn

Dr. Vivian Pinn served as the first full–time director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additionally, she was the first African American woman to chair an academic pathology department in the United States, at Howard University College of Medicine.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Pinn.

Dr. Esther M. Sternberg

Dr. Esther Sternberg is internationally recognized for her groundbreaking work on the mind–body connection in illness and healing.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Sternberg.

Dr. Donna M. Christian-Christensen

Dr. Donna Christian–Christensen is the first woman physician to serve in Congress and the first woman delegate for the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Christian–Christensen.

Dr. Nancy L. Snyderman

Dr. Nancy Snyderman had a decades’ long career in broadcast medical journalism, serving as a correspondent for ABC television’s Good Morning America for 15 years.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Snyderman.

Setting Their Sights

Before women could build careers as physicians, they had to fight even to be allowed to attend medical school. After proving that they were as capable as men, they went on to campaign for additional professional training and other career opportunities.

As part of the wider movement for women’s rights during the mid–1800s, women campaigned for admission to medical schools and the opportunity to learn and work alongside men in the professions. Such rights came slowly. Even after qualifying as physicians, women were often excluded from employment in medical schools, hospitals, clinics, and laboratories.

To provide access to these opportunities, many among the first generation of women physicians established women’s medical colleges or hospitals for women and children.

Persistence, ingenuity, and ability enabled women to advance into all areas of science and medicine. Courageously, they worked long and hard to succeed even where they were most unwelcome, such as in surgery and scientific research.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Setting Their Sights

Opening Doors

The first women to complete medical training and launch careers confronted daunting professional and social restrictions. To establish their rightful place as physicians and to expand opportunities for other women in medicine, they devised many strategies, establishing their own hospitals, schools, and professional societies. They excelled in their chosen fields of medical practice and scientific research—often while campaigning for political change and managing the administrative responsibilities and financial affairs of educational and medical institutions.

By succeeding in work considered “unsuitable” for women, these leaders overturned prevailing assumptions about the supposedly lesser intellectual abilities of women and the traditional responsibilities of wives and mothers.

Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell

When she graduated from New York’s Geneva Medical College, in 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in America to earn the M.D. degree. She supported medical education for women and helped many other women’s careers. By establishing the New York Infirmary in 1857, she offered a practical solution to one of the problems facing women who were rejected from internships elsewhere but determined to expand their skills as physicians. She also published several important books on the issue of women in medicine, including Medicine as a Profession For Women in 1860 and Address on the Medical Education of Women in 1864.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Mary Corinna Putnam Jacobi

Mary Putnam Jacobi was an esteemed medical practitioner and teacher, a harsh critic of the exclusion of women from the professions, and a social reformer dedicated to the expansion of educational opportunities for women. She was also a well–respected scientist, supporting her arguments for the rights of women with the scientific proofs of her time.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC–USZ62–61783

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer

Emily Dunning Barringer harnessed the benefits of a good education and gained the mentorship of a leading woman physician of her era, Dr. Mary Putnam Jacobi, to overcome barriers in her own career and to make it possible for other women physicians to serve their country during World War II. After first being denied an appointment at New York’s Gouverneur Hospital, she was later allowed to take up the position and became the hospital’s first woman medical resident and ambulance physician. During World War II, Barringer lobbied Congress to allow women physicians to serve as commissioned officers in the Army Medical Reserve Corps, and in 1943 the passing of the Sparkman Act granted women the right to receive commissions in the army, navy, and Public Health Service.

New York Times Archive

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer

Dr. Emily Dunning Barringer became the first woman medical resident and ambulance physician in New York. She also lobbied Congress to allow women physicians to receive commissions in the Armed Forces and the Public Health Service.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dunning Barringer.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Marie E. Zakrzewska

In 1862, Marie Zakrzewska, M.D., opened doors to women physicians who were excluded from clinical training opportunities at male–run hospitals, by establishing the first hospital in Boston—and the second hospital in America—run by women, the New England Hospital for Women and Children.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Marie E. Zakrzewska

Dr. Marie Zakrzewska founded the New England Hospital for Women and Children, the second hospital in the United States to be run by women physicians and surgeons.

Click on the video play button to watch a video Dr. Zakrzewska.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Ann Preston

As the first woman to be made dean of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP), Ann Preston campaigned for her students to be admitted to clinical lectures at the Philadelphia Hospital, and the Pennsylvania Hospital. Despite the hostility of the all–male student groups, she was determined to negotiate the best educational opportunities for the students of WMCP.

National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B030140

-

DigitalCollections

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Ann Preston

Dr. Ann Preston was the first woman dean of the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and advocated for women students to receive medical education.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Preston.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Sarah Reed Adamson Dolley

Sarah Adamson Dolley of Rochester, New York, was the first woman physician to complete a hospital internship. She was a founder of one of the first general women’s medical societies, the Practitioners’ Society of Rochester, New York, and the Provident Dispensary for Women and Children (an outpatient clinic for the working poor) established by the society. She was also the first president of the Women’s Medical Society of New York State.

Edward G. Miner Library, Rochester New York

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Sarah Reed Adamson Dolley

Dr. Sarah Adamson Dolley was the third woman medical graduate in the United States and the first woman to complete a hospital internship.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dolley.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones

Dr. Mary Dixon Jones became a world–renowned surgeon for her treatment of diseases of the female reproductive system, in a time when few women physicians were able to build a career in the specialty. She is credited as the first person in America to propose and perform a full hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) for the treatment of uterine myoma (a tumor of muscle tissue). She trained with Mary Putnam Jacobi in New York and is considered one of the leading women scientists of the late nineteenth century.

Courtesy of the New York Academy of Medicine Library, copy by RD Rubic

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones

Dr. Mary Amanda Dixon Jones was a renowned surgeon credited as the first person to propose and perform a full hysterectomy to treat a tumor in uterine muscle tissue.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dixon Jones.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Setting Their Sights

Challenging Racial Barriers

The first women of color who gained access to medical school confronted financial hardships, discrimination against women, and racism. For generations, their families had been enslaved or oppressed. They had been denied the means of making a living and access to decent medical care. Even to begin training, these women often had to work their way through medical school or seek funding from supporters of women’s and minorities’ rights.

Once they became doctors, these women played an important role in bringing better standards of care to their own communities and served as role models for other women.

Dr. Matilda Arabella Evans

Matilda Arabella Evans, who graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) in 1897, was the first African-American woman licensed to practice medicine in South Carolina. Evans’s survey of black school children’s health in Columbia, South Carolina, served as the basis for a permanent examination program within the South Carolina public school system. She also founded the Columbia Clinic Association, which provided health services and health education to families. She extended the program when she established the Negro Health Association of South Carolina, to educate families throughout the state on proper health care procedures.

South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

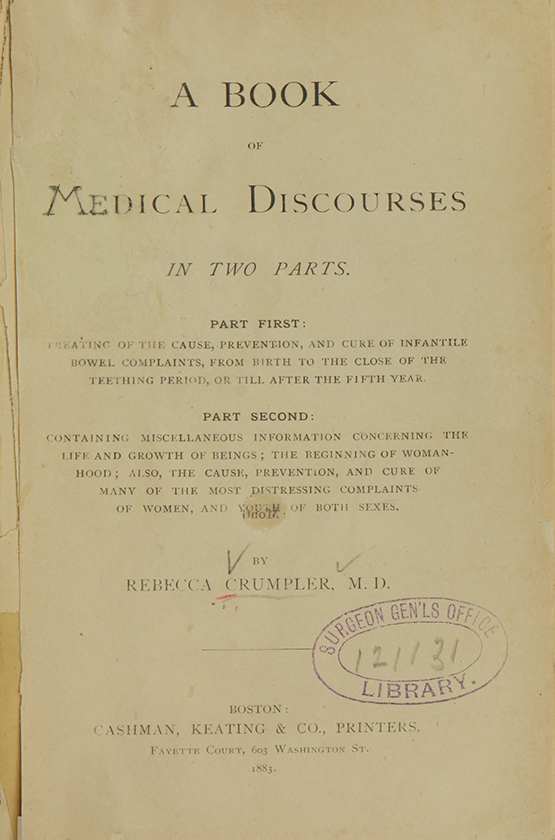

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

Rebecca Lee Crumpler challenged the prejudice that prevented African Americans from pursuing careers in medicine to became the first African American woman in the United States to earn an M.D. degree, a distinction formerly credited to Rebecca Cole. Although little has survived to tell the story of Crumpler’s life, she has secured her place in the historical record with her book of medical advice for women and children, published in 1883.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

Susan La Flesche Picotte was first person to receive federal aid for professional education, and the first American Indian woman in the United States to receive a medical degree. In her remarkable career she served more than 1,300 people over 450 square miles, giving financial advice and resolving family disputes as well as providing medical care at all hours of the day and night.

Susan La Flesche, early 1900s, when she returned to the Omaha Reservation

Nebraska State Historical Society Photograph Collections

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole

In 1867, Rebecca J. Cole became the second African American woman to receive an M.D. degree in the United States (Rebecca Crumpler, M.D., graduated from the New England Female Medical College three years earlier, in 1864). Dr. Cole was able to overcome racial and gender barriers to medical education by training in all–female institutions run by women who had been part of the first generation of female physicians graduating mid–century. Dr. Cole graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1867, under the supervision of Ann Preston, the first woman dean of the school, and went to work at Elizabeth Blackwell’s New York Infirmary for Women and Children to gain clinical experience.

National Library of Medicine

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole

Dr. Rebecca J. Cole was the first African American woman to receive an MD in the United States.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Cole.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens

In 1950, Dr. Helen Dickens was the first African American woman admitted to the American College of Surgeons. The daughter of a former slave, she would sit at the front of the class in medical school so that she would not be bothered by the racist comments and gestures made by her classmates. By 1969, she was associate dean in the Office for Minority Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania, and within five years had increased minority enrollment from three students to sixty–four.

National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B07139

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens

Dr. Helen Dickens was the first African American woman admitted to the American College of Surgeons. She served communities with limited access to health care, provided sex education to women living in poverty, and worked as a professor of surgery.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dickens.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier

Eliza Ann Grier was an emancipated slave who faced racial discrimination and financial hardship while pursuing her dream of becoming a doctor. To pay for her medical education, she alternated every year of her studies with a year of picking cotton. It took her seven years to graduate. In 1898, she became the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia, and although she was plagued with financial difficulties throughout her education and her career, she fought tenaciously for her right to earn a living as a woman doctor.

Archives and Special Collections on Women in Medicine, Drexel University College of Medicine

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier

Dr. Eliza Ann Grier was the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Grier.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Setting Their Sights

Confronting Glass Ceilings

By the early 1900s, women had made impressive inroads into the medical profession as physicians, but few had been encouraged to pursue careers as medical researchers. To succeed as scientists, despite opposition from male colleagues at leading institutions, women physicians persisted in gaining access to mentors, laboratory facilities, and research grants to build their careers.

The achievements of these innovators often went unrewarded or unacknowledged for years. Yet these resourceful researchers carved paths for other women to follow and eventually gained recognition for their contributions to medical science.

Dr. Florence Rena Sabin

Florence Rena Sabin was one of the first women physicians to build a career as a research scientist. She was the first woman on the faculty at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, building an impressive reputation for her work in embryology and histolology (the study of tissues). She also overturned the traditional explanation of the development of the lymphatic system by proving that it developed from the veins in the embryo and grew out into tissues, and not the other way around.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Mahomed sphygmograph, ca. 1880

Dr. May Edward Chinn

In 1926, May Edward Chinn became the first African American woman to graduate from the University and Bellevue Hospital Medical College. She practiced medicine in Harlem for fifty years. A tireless advocate for poor patients with advanced, often previously untreated diseases, she became a staunch supporter of new methods to detect cancer in its earliest stages.

George B. Davis, Ph.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori

Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori and her husband, Dr. Carl Cori, were the first married couple to receive a Nobel Prize in science. Gerty Cori was only the third woman ever to win a Nobel Prize, and was the first woman in America to do so.

Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori

Dr. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori became the first women in America to win a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Cori.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Louise Pearce

Louise Pearce, M.D., a physician and pathologist, was one of the foremost women scientists of the early 20th century. Her research with pathologist Wade Hampton Brown led to a cure for trypanosomiasis (African Sleeping sickness) in 1919.

Courtesy of the Rockefeller University Archives

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Louise Pearce

Dr. Louise Pearce’s research helped lead to a cure for trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness) in 1919.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Pearce.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Anna Wessels Williams

Anna Wessels Williams, M.D., worked at the first municipal diagnostic laboratory in the United States, at the New York City Department of Health. She isolated a strain of diphtheria that was instrumental in the development of an antitoxin for the disease. She was a firm believer in the collaborative nature of laboratory science, and helped build some of the more successful teams of bacteriologists, which included many women, working in the country at the time.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Anna Wessels Williams

Dr. Anna Wessels Williams isolated a strain of bacteria that scientists used to develop the treatment for diphtheria.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Wessels Williams.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright

Dr. Jane Wright analyzed a wide range of anti–cancer agents, explored the relationship between patient and tissue culture response, and developed new techniques for administering cancer chemotherapy. By 1967, she was the highest ranking African American woman in a United States medical institution.

National Library of Medicine

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright

Dr. Jane Cook Wright advanced chemotherapy techniques through her pioneering cancer research.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Wright.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Making Their Mark

Bringing fresh perspectives to the profession of medicine, women physicians often focused on issues that had received little attention-the social and economic costs of illness, new research and treatments for women and children, and the low numbers of women and minorities entering medical school and practice.

As the first to address some of these needs, women physicians often led the way in designing new approaches to public health policy, illness, and access to medical care. The revival of the civil rights and women's movements and passage of equal opportunity legislation in the 1960s led to a dramatic increase in the numbers of women and minorities entering medicine.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Making Their Mark

Caring for Communities

Many early advocates of the rightful place of women in the professions argued that women had a special obligation to those most at risk. By the first decades of the 1900s, women physicians were establishing innovative public health programs and labor reforms designed to protect the most vulnerable members of society.

By succeeding in work considered “unsuitable” for women, these leaders overturned prevailing assumptions about the supposedly lesser intellectual abilities of women and the traditional responsibilities of wives and mothers. [or As the century progressed, the discrimination experienced by women and minorities fueled broad social movements for change. Women physicians involved in this struggle became advocates for those suffering from neglect or abuse.]

Dr. Alice Hamilton

Alice Hamilton was a leading expert in the field of occupational health. She was a pioneer in the field of toxicology, studying occupational illnesses and the dangerous effects of industrial metals and chemical compounds on the human body. She published numerous benchmark studies that helped raise awareness of dangers in the workplace. In 1919, she became the first woman appointed to the faculty at Harvard Medical School, serving in their new Department of Industrial Medicine. She also worked with the state of Illinois, the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the League of Nations on various public health issues.

Alice Hamilton, M.D., National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B014009

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Martha May Eliot

Dr. Martha May Eliot worked for the Children’s Bureau, a national agency established in 1912 to improve the health and welfare of American children, for over 25 years. First employed as director of the bureau’s Division of Child and Maternal Health, Eliot went on to become assistant chief, and then chief, of the whole organization. She was the only woman to sign the founding document of the World Health Organization, and an influential force in children’s health programs worldwide.

Martha May Eliot, M.D., National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B09844, photograph by Bachrach

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Healthy femur (left) and femur showing the effects of rickets (right)

Children’s bones contain growth plates—areas of soft cartilage that lengthen before being replaced by hard bone. With rickets, the bone's growth plate widens as soft cartilage cells accumulate.

The bones of a child with rickets (right) are too soft and bend under the pressure of body weight. Proper diet and adequate sunlight provide the vitamin D necessary to build strong bones (left). Dr. Martha May Eliot’s work provided insight on how to treat this disease.

National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias

Through her efforts to support abortion rights, abolish enforced sterilization, and provide neonatal care to underserved people, Helen Rodriguez–Trias expanded the range of public health services for women and children in minority and low–income populations in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Helen Rodriguez–Trias, M.D., JoEllen Brainin–Rodriguez M.D., photograph by Rafael Pesquera

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen Rodriguez-Trias

Dr. Helen Rodriguez–Trias worked to improve access to health services for women and children in underserved communities, advocated for women’s rights, and served as the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Rodriguez–Trias.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone brought an uncomfortable subject to the forefront of public debate in her work in sex education. Beginning in the 1950s, when public discussion of such issues was considered highly controversial, Dr. Calderone flouted convention by speaking out in the first place, and as a woman broaching such a topic. In 1964, she founded the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), to promote sex education for children and young adults.

The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone

Dr. Mary Steichen Calderone advocated for sex education, founding the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS).

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Calderone.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Dorothy Celeste Boulding Ferebee

Dr. Dorothy Ferebee was a tireless advocate for racial equality and women’s health care. In 1925, in a derelict section of Capitol Hill, she established Southeast Neighborhood House, to provide health care for impoverished African Americans. She also set up the Southeast Neighborhood Society, with playground and day care for children of working mothers. At Howard University Medical School, she was appointed director of Health Services. She was founding president of the Women’s Institute an organization that serves educational, community, government, and non–profit organizations, as well as individual patients.

Ferebee/Edwards Papers, Moorland–Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Dorothy Celeste Boulding Ferebee

Dr. Dorothy Boulding Ferebee advocated for civil rights, women’s health care, and public health, and worked to expand access to health care in poor African American communities.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Ferebee.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Fernande Marie Pelletier

Sister Fernande Pelletier, M.D., a member of the Medical Mission Sisters (founded 1925), has worked overseas for more than forty years, carrying out the mission of her order in Ghana and offering medical care to underserved populations. Her incredible devotion and service has been rewarded by the Ghanaian government, and in rural communities far from fully–equipped hospitals, she continues to care for those in need.

Medical Mission Sisters

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Fernande Marie Pelletier

Dr. Fernande Pelletier works as a Medical Mission Sister to deliver health care to underserved communities in Ghana.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Pelletier.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. M. Joycelyn Elders

Joycelyn Elders, the first person in the state of Arkansas to become board certified in pediatric endocrinology, was the sixteenth Surgeon General of the United States, the first African American and only the second woman to head the U.S. Public Health Service. Long an outspoken advocate of public health, Elders was appointed Surgeon General by President Clinton in 1993.

Parklawn Health Library

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. M. Joycelyn Elders

Dr. Joycelyn Elders is the first African American and second woman to serve as the U.S. surgeon general.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Elders.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Making Their Mark

Making Discoveries

Women physicians, who have often been discouraged from pursuing the most prestigious specialties, nevertheless have seized opportunities in medical research and practice. In some instances, they have brought new expertise to neglected areas of research. In others, they have carved out new roles for their interests within existing specialties.

The breakthrough discoveries in medical research of women physicians benefit all of us, patients and practitioners.

Dr. Virginia Apgar

Virginia Apgar, M.D., the first woman to become a full professor at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, designed the first standardized method for evaluating the newborn’s transition to life outside the womb–the Apgar Score.

The Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen Brooke Taussig

Helen Brooke Taussig is known as the founder of pediatric cardiology for her innovative work on “blue baby” syndrome. In 1944, Taussig, surgeon Alfred Blalock, and surgical technician Vivien Thomas developed an operation to correct the congenital heart defect that causes the syndrome. Since then, their operation has prolonged thousands of lives, and is considered a key step in the development of adult open heart surgery the following decade. Dr. Taussig also helped to avert a thalidomide birth defect crisis in the United States, testifying to the Food and Drug Administration on the terrible effects the drug had caused in Europe.

The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. M. Irené Ferrer

As a young physician, Dr. Irené Ferrer was the first woman to serve as chief resident at Bellevue Hospital, where she was given a prestigious opportunity: to work with a leading team of cardiologists who were developing the cardiac catheter. Dr. Ferrer played a vital role in the Nobel prize–winning project, which was also an important step in the development of open–heart surgery.

Marianne Legato, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. M. Irené Ferrer

Dr. Irené Ferrer helped develop the cardiac catheter and was the first woman chief resident at Bellevue Hospital, Columbia University.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Ferrer.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston

Marilyn Hughes Gaston, M.D., faced poverty and prejudice as a young student, but was determined to become a physician. She has dedicated her career to medical care for poor and minority families, and campaigns for health care equality for all Americans. Her 1986 study of sickle–cell disease led to a nationwide screening program to test newborns for immediate treatment, and she was the first African American woman to direct a public health service bureau (the Bureau of Primary Health Care in the United States Department of Health and Human Services).

Parklawn Health Library

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston did important research into sickle–cell disease and became the first African American woman to direct a bureau of the U.S. Public Health Service.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Gaston.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Janet Davison Rowley

In the early 1970s, Dr. Janet Rowley identified a process of “translocation,” or the exchange of genetic material between chromosomes in patients with leukemia. This discovery, along with Dr. Rowley’s subsequent work on chromosomal abnormalities, has revolutionized the medical understanding of the role of genetic exchange and damage in causing disease.

David Bentley Photography, Inc.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Janet Davison Rowley

Dr. Janet Davison Rowley identified the translocation of chromosomes as the cause of leukemia and other cancers.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Rowley.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Katherine M. Detre

Dr. Katherine M. Detre has been named a distinguished professor of epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh’s Graduate School of Public Health, in recognition of her many achievements. A leading expert in epidemiological analysis, she has designed and led large-scale health studies undertaken across the country.

Katherine Maria Drechsler Detre, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Katherine M. Detre

Dr. Katherine M. Detre was a leading epidemiologist, spearheading large–scale health studies.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Detre.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Ruth E. Dayhoff

Ruth E. Dayhoff is at the forefront of medical informatics. As the medical technologies used to diagnose disease have become more complex, corresponding new information systems have been developed to analyze, store, and present the new types of data. Dr. Dayhoff followed her mother, Dr. Margaret Oakley Dayhoff, into the field she pioneered in the 1960s, heading the VistA Imaging Project at the Department of Veterans Affairs—a unique, innovative system that will eventually be implemented in all VA medical centers across the United States.

Ruth E. Dayhoff, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Ruth E. Dayhoff

Dr. Ruth E. Dayhoff is a leader in the field of medical informatics, heading the VistA Imaging Project at the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Dayhoff.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Making Their Mark

Enriching Medical Education

Many patients find that doctors from their own communities are better able to understand their concerns. Because the women physicians who train future physicians recognize the value of diverse perspectives, they are developing innovative teaching strategies and programs to attract students from many backgrounds to all specialties. To help students succeed in medical school, women physicians act as mentors, advisors, and role models.

Women physicians are enlarging the base of students who aspire to careers in medicine, as well as expanding the skills that all medical students take into successful practice.

Dr. Katherine A. Flores

Katherine A. Flores established two programs to encourage disadvantaged students to pursue careers in medicine: the Sunnyside High School Doctor’s Academy and the middle school Junior Doctor’s Academy. These programs provide academic support and health science enrichment to young people who might not otherwise be successful in their educational experiences—or be thinking about medical careers.

Katherine A. Flores, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Linda Dairiki Shortliffe

Dr. Linda M. Dairiki Shortliffe built a successful career in the relatively new field of pediatric urology when very few women surgeons were doing such work. Since 1988, she has been at the Stanford University School of Medicine Medical Center and Packard Children’s Hospital as chief of pediatric urology. Since 1993, she has also been director of the Urology Residency Program at Stanford, and has been successful in recruiting more women physicians to her specialty. She noted that the numbers have grown rapidly; when she got her board certification in urology in 1983, there were only fifteen women urologists in the U.S. Now there are more than two hundred.

Linda M. Dairiki Shortliffe, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Paula L. Stillman

While teaching pediatrics at the University of Arizona in the 1970s, Paula Stillman needed a reliable way to evaluate her students’ clinical competence. Her solution was to train and use “patient instructors” or “standardized patients.” Stillman’s system is a competency based program, Objective Structured Clinical Evaluations (OSCE), developed to assess medical students, foreign medical graduates, and U.S. doctors in danger of losing their licenses. Her system has also been adopted by medical schools in China.

Paula L. Stillman, M.D.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Paula L. Stillman

Dr. Paula L. Stillman developed a tool that is used to evaluate the clinical competence of medical students, foreign medical graduates, and U.S. doctors in danger of losing their licenses.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Stillman.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Edithe J. Levit

In 1986, The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) bestowed their Special Recognition Award on Dr. Edithe J. Levit, the first woman president and CEO of a national medical association, the National Board of Medical Examiners. Dr. Levit introduced new technologies and strategies for the examination of medical students, spearheading change to improve standards. Carefully managing the needs of both medical schools and examiners, she promoted dynamic changes that included the introduction of audiovisual tools, computer–based exams, and the first self–assessment test of the American College of Physicians.

Edithe J. Levit, M.D

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Edithe J. Levit

Dr. Edithe J. Levit established new ways to evaluate doctors’ clinical competence and was the first woman president of a national medical association, the National Board of Medical Examiners.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Levit.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Rita Charon

As director of the program in humanities and medicine and the clinical skills assessment program at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, Rita Charon, M.D., developed an innovative new teaching method. The “parallel chart” system brings literature and medicine together to improve the doctor–patient relationship, and forms part of the only narrative competency course in a United States medical school.

Rita Charon, M.D., M.A., Ph.D.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Rita Charon

Dr. Rita Charon pioneered a form of medical education that incorporates literature to help clinicians better understand the patient experience.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Charon.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Barbara Bates

Barbara Bates further developed the role of the nurse–practitioner, and wrote a guide to patient history–taking that has become the standard text for health practitioners and medical students. Her book, Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, first published in 1974, has been published in several revised editions and includes a twelve–part video supplement, A Visual Guide to Physical Examination.

Barbara Bates, 1990

Joan E. Lynaugh, Ph.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Barbara Bates

Dr. Barbara Bates wrote Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, a standard text for health practitioners, and helped to develop the role of the nurse practitioner.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Bates.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Barbara Ross-Lee

Barbara Ross–Lee, D.O., has worked in private practice, for the U.S. Public Health Service, and on numerous committees, and in 1993 was the first African American woman to be appointed dean of a United States medical school.

Barbara Ross–Lee, M.A., D.O.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Barbara Ross-Lee

Dr. Barbara Ross–Lee was the first African America woman to be appointed dean of a U.S. medical school.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Ross–Lee.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Changing Medicine, Changing Life

Confronting the multiplying challenges of health care, women physicians have joined the highest ranks of medical administration and research. As leaders, they make choices that benefit communities across America and around the world. As healers, they identify and respond to many of the most urgent crises in modern medicine, from the needs of underserved communities, to AIDS and natural and man–made disasters.

Their influence reaches across the profession out into our lives, redefining women’s roles and society’s responsibilities. By changing the face of medicine, women physicians are changing our world.

Changing Medicine, Changing Life

Caring for People

Calling upon the art as well as the science of medicine, women physicians treat the whole patient and the whole spectrum of health care needs. The perspectives they bring to care for the living and comfort for the dying encompass all aspects of the medical and emotional well–being of the healthy, the ill, and the at–risk.

This multifaceted approach is reshaping the way that both practitioners and patients strive to improve the quality of life and deal with disease and injury, while widening the scope of medical care for individuals and communities.

Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord

Dr. Lori Arviso Alvord bridges two worlds of medicine—traditional Navajo healing and conventional Western medicine—to treat the whole patient. She provides culturally competent care to restore balance in her patients’ lives and to speed their recovery.

Lori Arviso Alvord, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross

Elisabeth Kübler–Ross, a Swiss–born American psychiatrist, pioneered the concept of providing psychological counseling to the dying. In her first book, On Death and Dying (published in 1969), she described five stages she believed were experienced by those nearing death—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. She also suggested that death be considered a normal stage of life, and offered strategies for treating patients and their families as they negotiate these stages. The topic of death had been avoided by many physicians and the book quickly became a standard text for professionals who work with terminally ill patients. Hospice care has subsequently been established as an alternative to hospital care for the terminally ill, and there has been more emphasis on counseling for families of dying patients.

Ken Ross Photography

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Margaret Hamburg

Margaret Hamburg, one of the youngest people ever elected to the Institute of Medicine (IoM, an affiliate of the National Academy of Sciences), is a highly regarded expert in community health and bio–defense, including preparedness for nuclear, biological, and chemical threats. As health commissioner for New York City from 1991 to 1997, she developed innovative programs for controlling the spread of tuberculosis and AIDS.

Margaret Hamburg, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Margaret Hamburg

Dr. Margaret Hamburg is a leader in public health who developed programs for controlling the spread of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in the 1990s.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Hamburg.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Leona Baumgartner

From 1954 to 1962, Leona Baumgartner, M.D., served as the first woman commissioner of New York City’s Department of Health. She used her position to bring no–nonsense health and hygiene advice to millions of Americans via regular television and radio broadcasts, and by sending health care professionals to visit schools and church groups. Throughout her career she broadened the scope of public health by teaching preventive medicine in easy–to–understand brochures, and helped to improve the health of New York’s poorest and most vulnerable.

National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine, B02511

-

DigitalCollections

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Leona Baumgartner

Dr. Leona Baumgartner was the first woman to become commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and pioneered health education programs and health services in poor communities.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Baumgartner.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Christine Karen Cassel

“Pursuing difficult questions — in science and in policy — takes one to interesting places,” says Christine Cassel, M.D., a renowned expert in geriatric medicine and medical ethics. She works to improve quality of life for elderly patients, challenging out–of–date ideas about what can be expected in the aging process.

Christine Karen Cassel, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Christine Karen Cassel

Dr. Christine Karen Cassel is a leading expert in geriatrics and medical ethics and was the first woman president of the American College of Physicians.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Cassel.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. JoAnn Elisabeth Manson

Dr. JoAnn Manson has been a leading researcher in the two largest women’s health research projects ever launched in the United States—the first large scale study of women begun in 1976 as the Harvard Nurses’ Health Study, and the National Institute of Health’s Women’s Health Initiative, which involved 164,000 healthy women. Until the early 1990s, research on human health was usually done from all–male subject groups, and the results generated were thought to apply to both sexes. Federal regulation now mandates the inclusion of women in all research studies, as men and women may react differently to certain diseases and drug remedies, a fact Dr. Manson’s research efforts have helped to establish.

JoAnn Elisabeth Manson, M.D., Dr.P.H.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Joann Elisabeth Manson

Dr. JoAnn Elizabeth Manson is a leading researcher in women’s health and public health.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Manson.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. JudyAnn Bigby

JudyAnn Bigby, M.D., is director of the Harvard Medical School Center of Excellence in Women’s Health. She is devoted to the health care needs of underserved populations, focusing especially on women’s health. She is also nationally recognized for her pioneering work educating physicians on the provision of care to people with histories of substance abuse.

JudyAnn Bigby, M.D., Photo by Michael T. Quan and Courtesy of Patriots Trail Girl Scout Council

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. JudyAnn Bigby

Dr. JudyAnn Bigby serves as the director of Harvard Medical School’s Center of Excellence in Women’s Health and works to address the health care needs of vulnerable populations.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Bigby.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Changing Medicine, Changing Life

Transforming the Profession

Many women physicians strive to balance their personal and professional lives, as well as the needs of individual patients and entire communities. They are promoting reforms to eradicate the professional barriers that many of them faced in their own careers and working to change the way that medicine is taught and practiced.

Drawing on their own interests and experiences, women physicians are instituting changes that have far–reaching benefits for the health and happiness of families, communities, and medical practitioners themselves.

Dr. Perri Klass

As a pediatrician, writer, wife, and mother—Perri Klass has demonstrated how medicine is integral to the health of families and communities, and how doctors themselves struggle to balance the conflicting needs of profession, self, and family. With her love of literature and her involvement with literacy, Klass is acutely aware of the importance of reading to personal and professional success. As medical director of Reach Out and Read, a national program which makes books and advice about reading to young children part of every well–child visit, she encourages other pediatricians to foster pre–reading skills in their young patients.

Reach Out and Read National Center

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Susan M. Briggs

Susan M. Briggs, a trauma surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, established and became the first director of the International Medical Surgical Response Team (IMSuRT), an emergency response team that, on short notice, organizes and sends teams of doctors, nurses, and other health professionals from throughout New England to emergencies around the globe.

Susan M. Briggs, M.D., M.P.H.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Edith Irby Jones

In 1948, nine years before the “Little Rock Nine” integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, Edith Irby Jones became the first black student to attend racially mixed classes in the South, and the first black student to attend the University of Arkansas School of Medicine. Her enrollment in a previously segregated southern medical school made news headlines across the nation.

Edith Irby Jones, M.D.

Edith Irby Jones, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Edith Irby Jones

Dr. Edith Irby Jones was the first woman to be elected president of the National Medical Association and the first African American to graduate from University of Arkansas School of Medicine (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.)

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Jones.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Leah J. Dickstein

Psychiatrist Leah J. Dickstein is a former president of the American Medical Women’s Association and vice president of the American Psychiatric Association. Her innovative Health Awareness Workshop Program, at the University of Louisville, is based on her experience attending medical school while raising a family. The popular program, which covers everything from individual well–being to personal relationships, as well as race and gender issues, has made the University of Louisville one of the nation’s most family–friendly medical colleges.

Leah J. Dickstein, M.D., M.A.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Leah J. Dickstein

Dr. Leah J. Dickstein developed a program to help medical students balance their studies and family lives and was president of the American Medical Women’s Association.

Click on the video play button to watch a video on Dr. Dickstein.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Barbara Barlow

Barbara Barlow was the first woman to train in pediatric surgery at Babies Hospital, Columbia University Medical Center (now called Babies’ and Children’s Hospital of New York). By researching and documenting the causes of injuries to children in Harlem, and increasing public education about their prevention, she has helped to dramatically reduce accidents and injuries to inner–city children in New York and throughout the United States.

Barbara Barlow, M.D., M.A.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Barbara Barlow

Dr. Barbara Barlow founded the Injury Free Coalition for Kids and helped increase public education on how to prevent childhood injuries.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Barlow.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Marianne Schuelein

As a pediatric neurologist at Georgetown University Hospital in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Marianne Schuelein came to understand the problems of affordable child care from her own experience as a working mother. In 1973, as vice president of the District of Columbia chapter of the American Woman’s Medical Association, she decided to present the issue directly to Albert Ullman (D–Oregon), chair of the Ways and Means Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1976, Congress passed a law allowing child care tax deductions, enabling more women to work outside the home.

Marianne Schuelein, M.D.

Marianne Schuelein, M.D.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Marianne Schuelein

Dr. Marianne Schuelein campaigned for childcare tax deductions, which Congress pass into law in 1976, enabling more women to work outside the home.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Schuelein.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Changing Medicine, Changing Life

Taking the Lead

In recent decades, women physicians have risen to the very top ranks of the institutions that lead medical research and define the highest standards of practice. Deciding which issues to focus upon, they direct research and funding and are instrumental in implementing the policies, developing the drugs and treatments, and drafting the legislation to meet emerging medical challenges.

From high–profile, influential positions, women physicians provide examples and encouragement, as well as career opportunities, for other women who hope to practice medicine.

Dr. Antonia Novello

When Dr. Antonia Novello was appointed Surgeon General of the United States by President George Bush in 1990, she was the first woman—and the first Hispanic—ever to hold that office. Her appointment came after nearly two decades of public service at the National Institutes of Health, where she took a role in drafting national legislation regarding organ transplantation.

Antonia Novello M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H.

Antonia C. Novello, M.D., M.P.H., Dr.P.H.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Catherine D. DeAngelis

In her role as the first woman editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Catherine DeAngelis, M.D., has made a special effort to publish substantive scientific articles on women’s health issues. The journal plays an important role in bringing new research to light, and featured articles can lead to fundamental changes in treatment. Under her editorship, the journal published a landmark study questioning the benefits of hormone replacement therapy in 2002. She also served as editor of the Archive of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, from 1993 to 2000.

Catherine DeAngelis

Catherine DeAngelis, M.D., M.P.H.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Ruth L. Kirschstein

As director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from 1974 to 1993, Dr. Ruth Kirschstein was the first woman institute director at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Throughout her career, she has worked as an administrator, fundraiser, and scientific researcher, investigating possible public health responses in the midst of crisis and conservatism.

Ruth L. Kirschstein, M.D.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Ruth L. Kirschstein

Dr. Ruth L. Kirschstein served as director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, becoming the first woman director of an institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Kirschstein.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen M. Ranney

Dr. Helen Ranney’s landmark research during the 1950s was some of the earliest proof of a link between genetic factors and sickle cell anemia. She went on to become the first woman to chair the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, and was the first woman president of the Association of American Physicians from 1984 to 1985.

Helen M. Ranney, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Helen M. Ranney

Dr. Helen M. Ranney made pivotal contributions to sickle cell anemia research and became the first woman president of the Association of American Physicians.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Ranney.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Audrey Forbes Manley

Dr. Audrey Forbes Manley received a music scholarship to study at Spelman College in Atlanta. She took the opportunity to expand her education and interests and moved into the sciences. She was appointed Assistant Surgeon General in 1988, and is the first African American woman to hold a position of that rank in the United States Public Health Service. In 1997, she returned to Spelman, after forty years in medicine, to serve as president of the college.

Parklawn Health Library

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Audrey Forbes Manley

Dr. Audrey Forbes Manley was the first African American woman to achieve the rank of assistant surgeon general (Rear Admiral in the Public Health Service.)

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Manley.

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Frances K. Conley

In 1966, Frances Krauskopf Conley became the first woman to pursue a surgical internship at Stanford University Hospital, and in 1986, she became the first tenured full professor of neurosurgery at a medical school in the United States. In 1991, she risked her career when she drew public attention to the sexist environment which, she argued, pervaded Stanford University Medical Center.

Frances K. Conley, M.D., M.S.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Frances K. Conley

Dr. Frances K. Conley was the first woman to be a full tenured professor of neurosurgery at a medical school in the United States.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Conley.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Bernadine Healy

Cardiologist Bernadine Healy is a physician, educator, and health administrator who was the first woman to head the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Known for her outspoken, innovative policymaking, Dr. Healy has been particularly effective in addressing medical policy and research pertaining to women.

Bernadine Healy, M.D.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Bernadine Healy

Dr. Bernadine Healy was the first woman to direct the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Healy.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Paula A. Johnson

Dr. Paula Johnson is a women’s health specialist and a pioneer in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease. She conceived of and developed one of the first facilities in the country to focus on heart disease in women.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Paula A. Johnson

Dr. Paula A. Johnson is a pioneering specialist in cardiovascular disease and developed one of the first facilities dedicated to heart disease in women.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Johnson.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Joan Y. Reede

Dr. Joan Reede works to recruit and prepare minority students for jobs in the biomedical professions, and to promote better health care policies for the benefit of minority populations. In 2001, she became Harvard Medical School’s first dean for diversity and community partnership. She is the first African American woman to hold that rank at HMS and one of the few African American women to hold a deanship at a medical school in the United States.

Joan Y. Reede, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Dr. Joan Y. Reede

Dr. Joan Y. Reede was appointed Harvard Medical School’s first dean for diversity and community partnership and has worked to bring more minority students into the health professions.

Click on the video play button to watch an interview with Dr. Reede.

-

MedlinePlus

-

Copy Link

Copied

Introduction

1 of 14

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

- Anatomist |Govard Bidloo (1649–1713)

- Type |Copperplate engraving with etching

Egestas purus viverra accumsan in nisl. Vulputate dignissim suspendisse in est ante in nibh mauris cursus. Consectetur purus ut faucibus pulvinar elementum integer enim neque volutpat. Massa sapien faucibus et molestie ac feugiat sed lectus vestibulum. Id diam vel quam elementum pulvinar etiam. Tristique sollicitudin nibh sit amet commodo nulla facilisi. Odio euismod lacinia at quis risus sed vulputate odio.