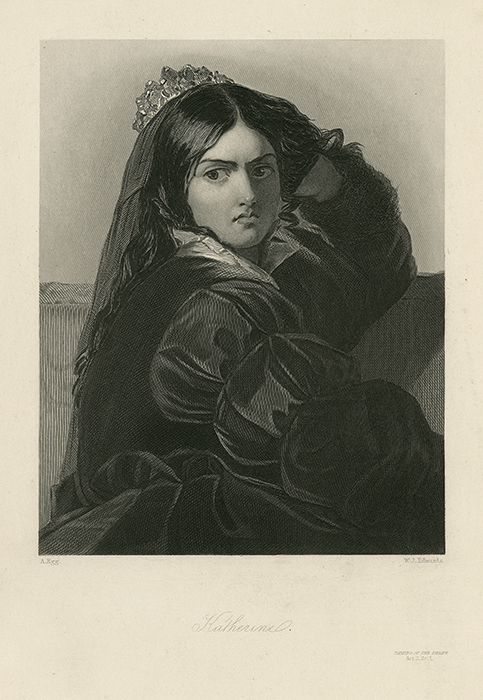

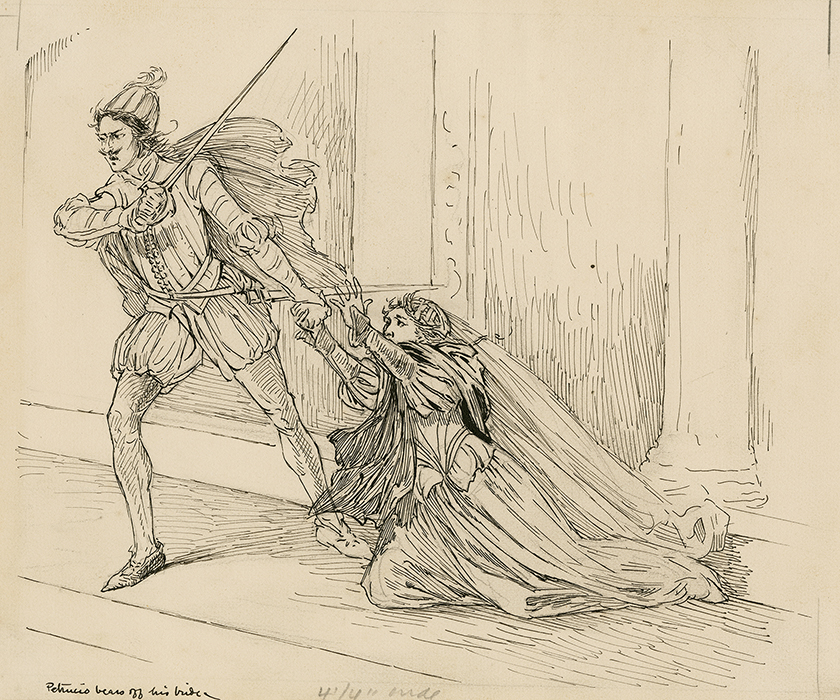

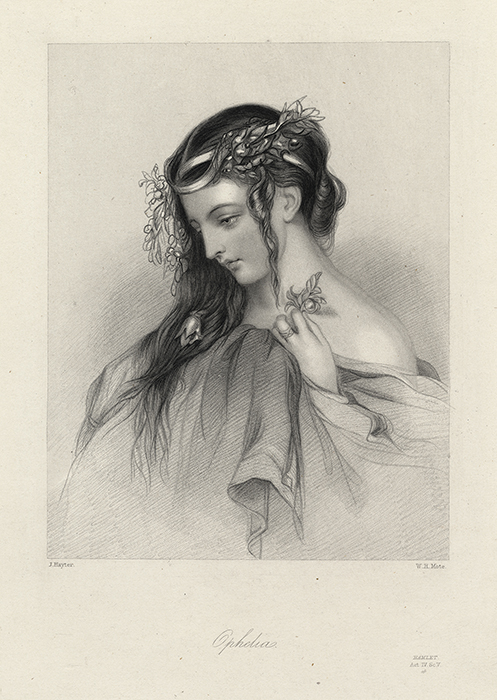

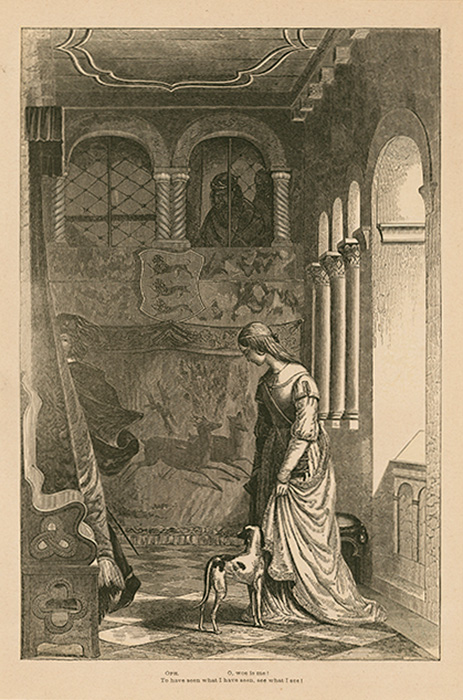

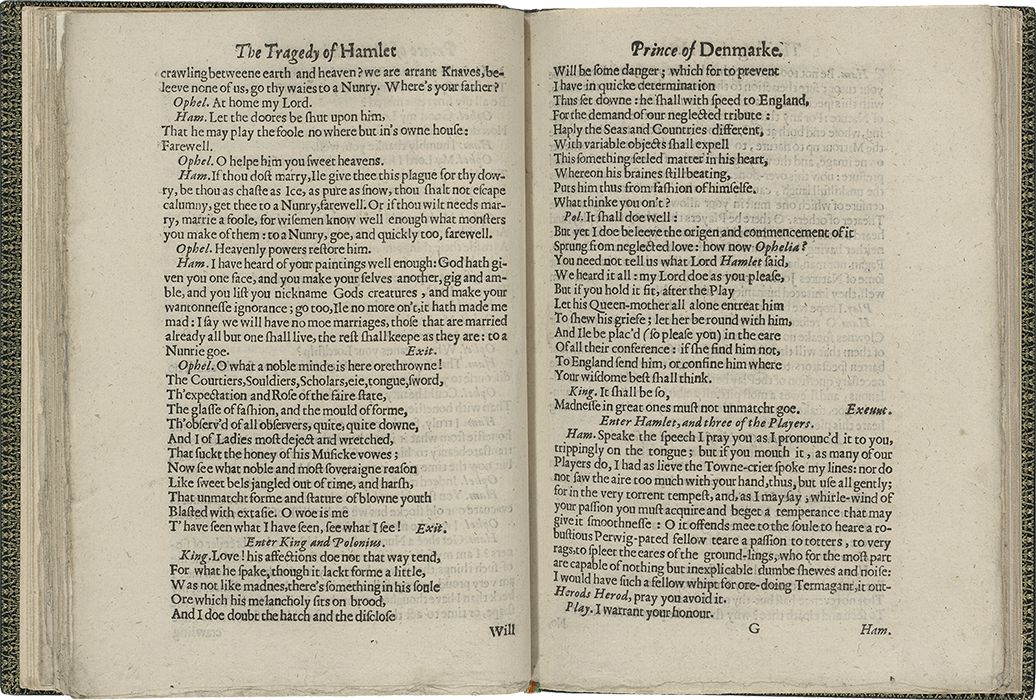

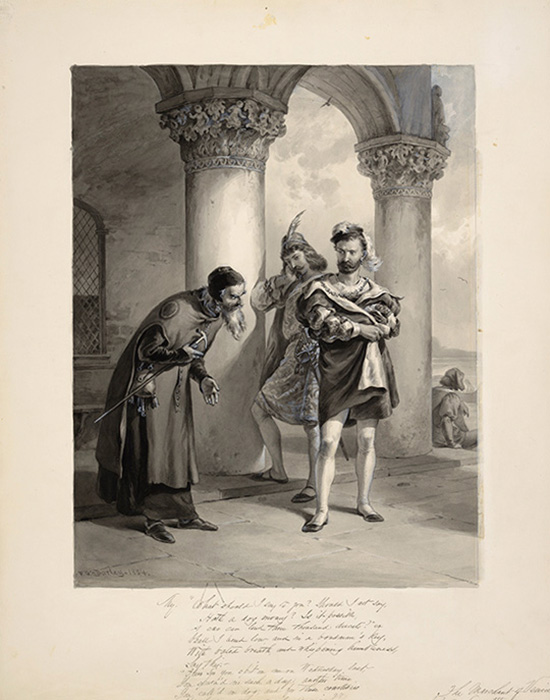

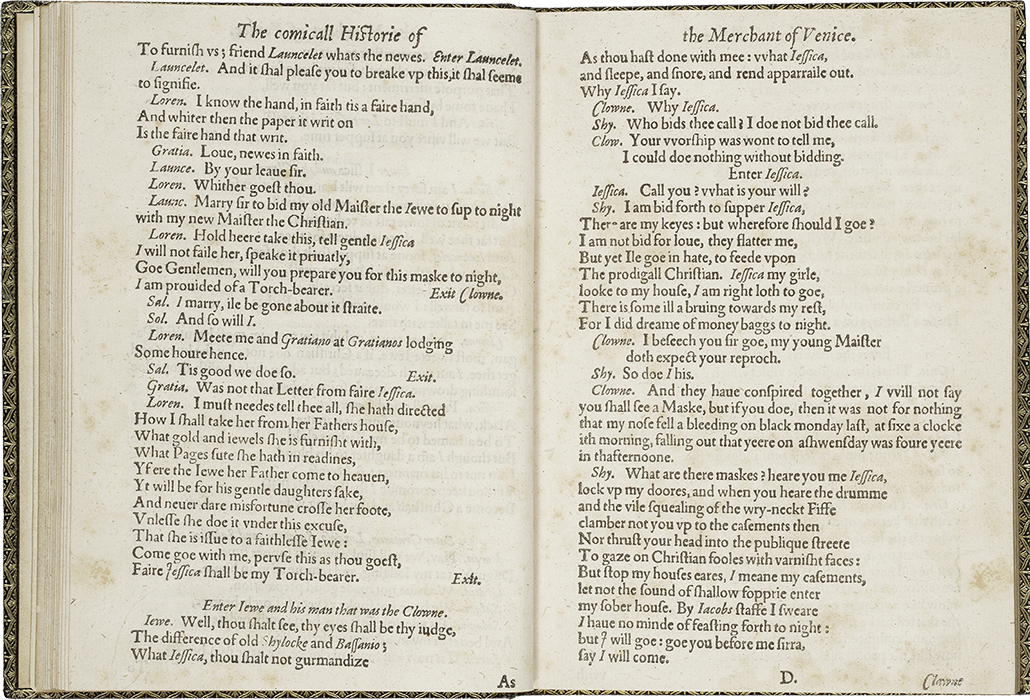

William Shakespeare created characters that are among the richest and most humanly recognizable in all of literature.

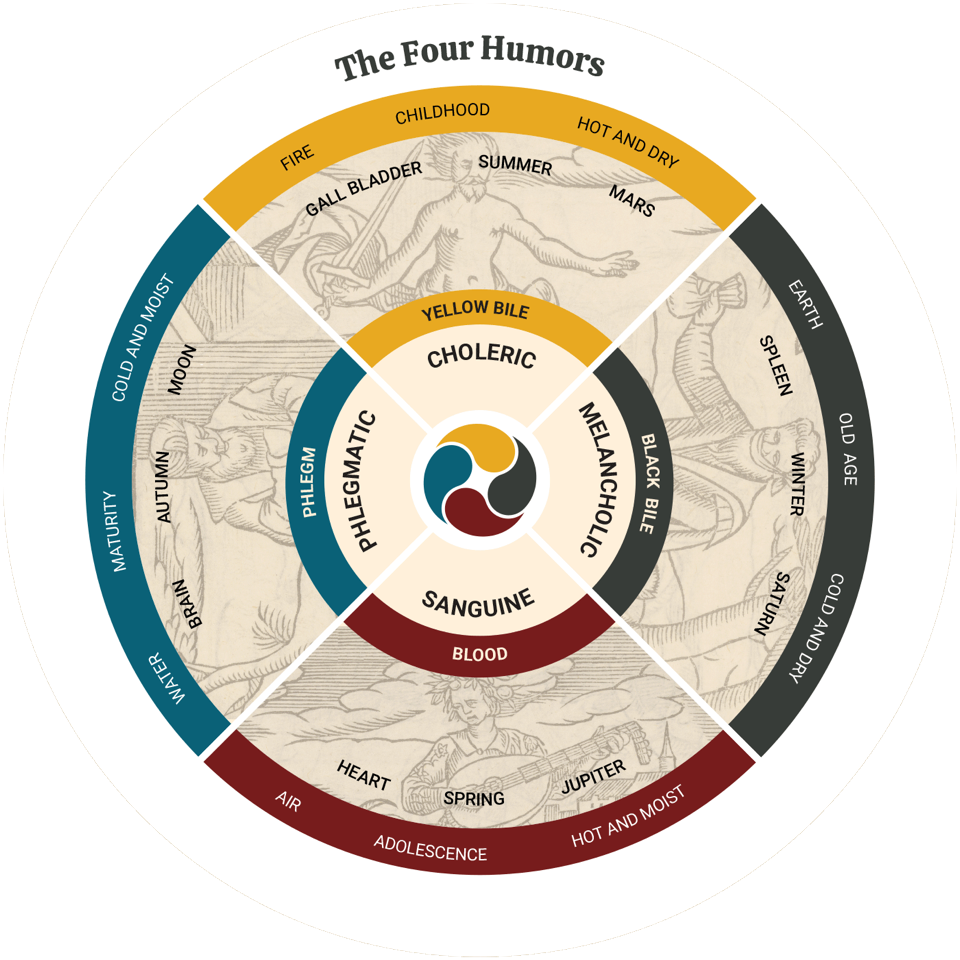

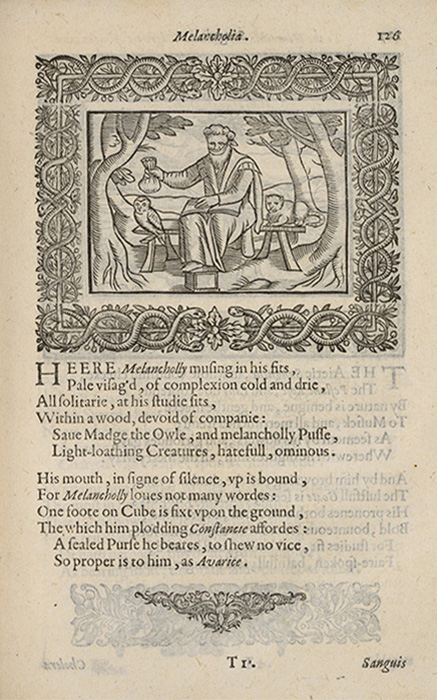

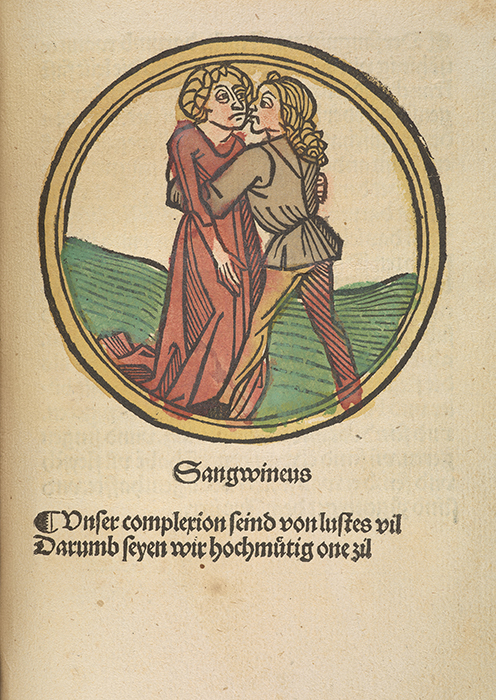

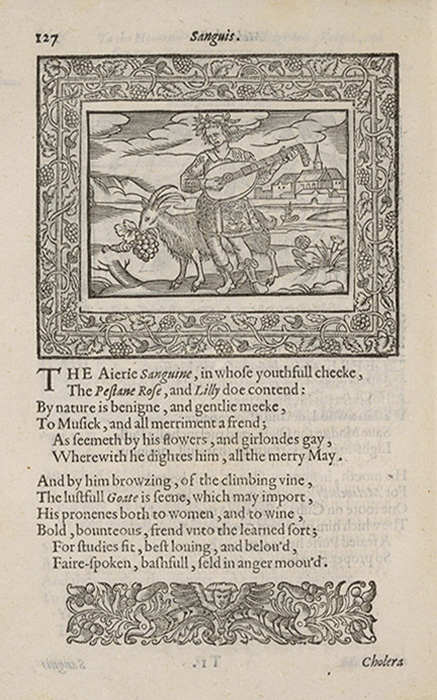

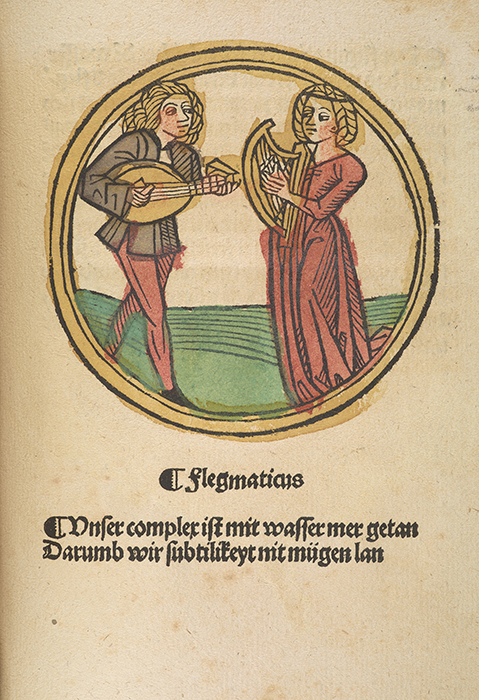

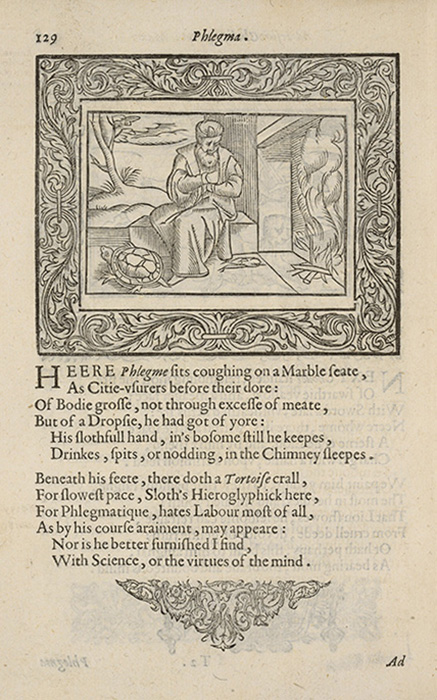

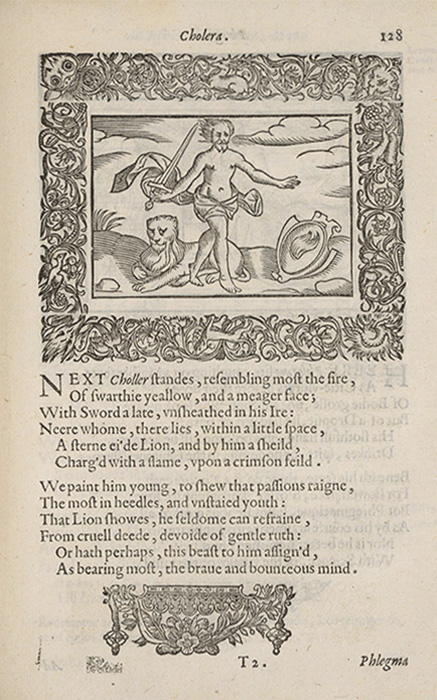

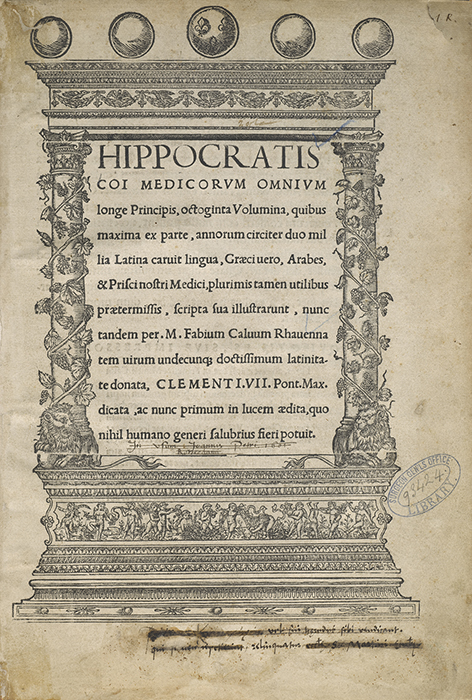

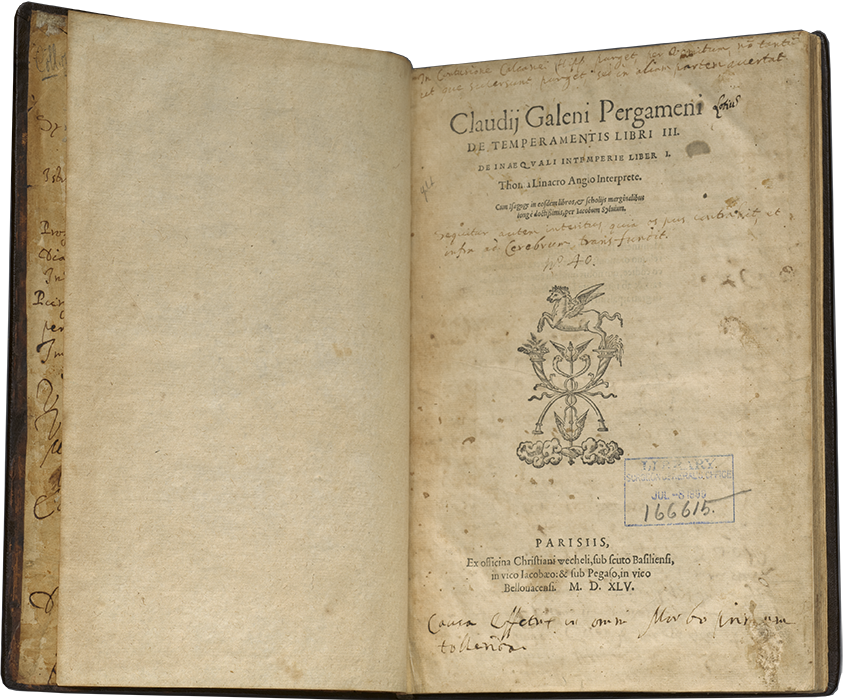

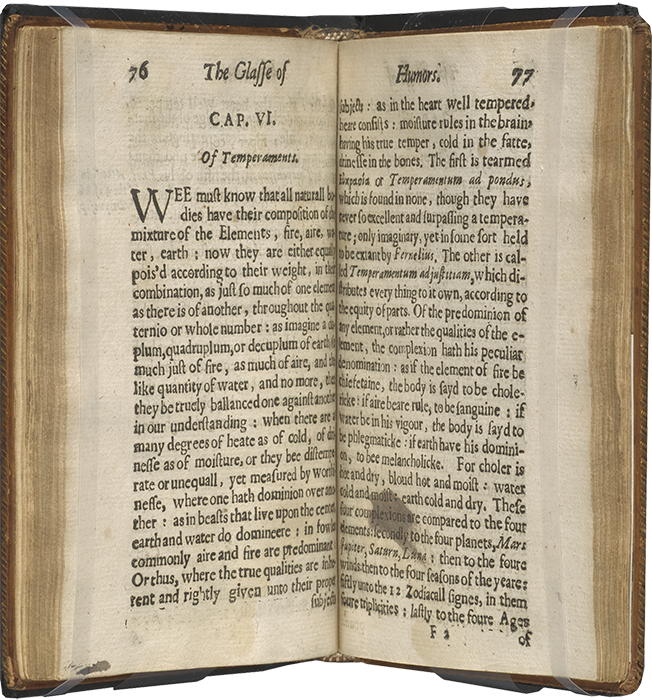

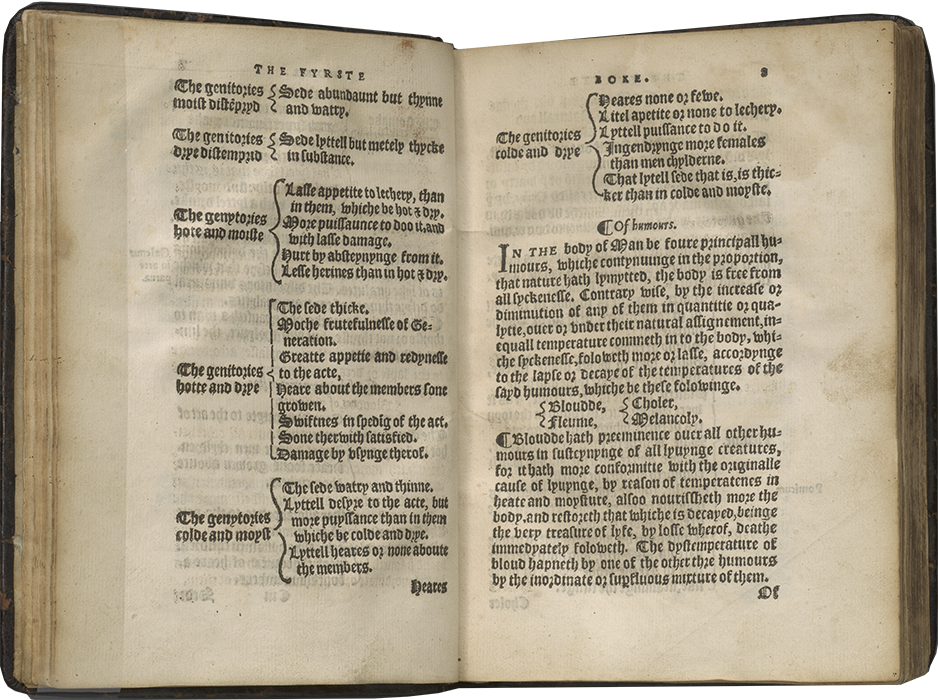

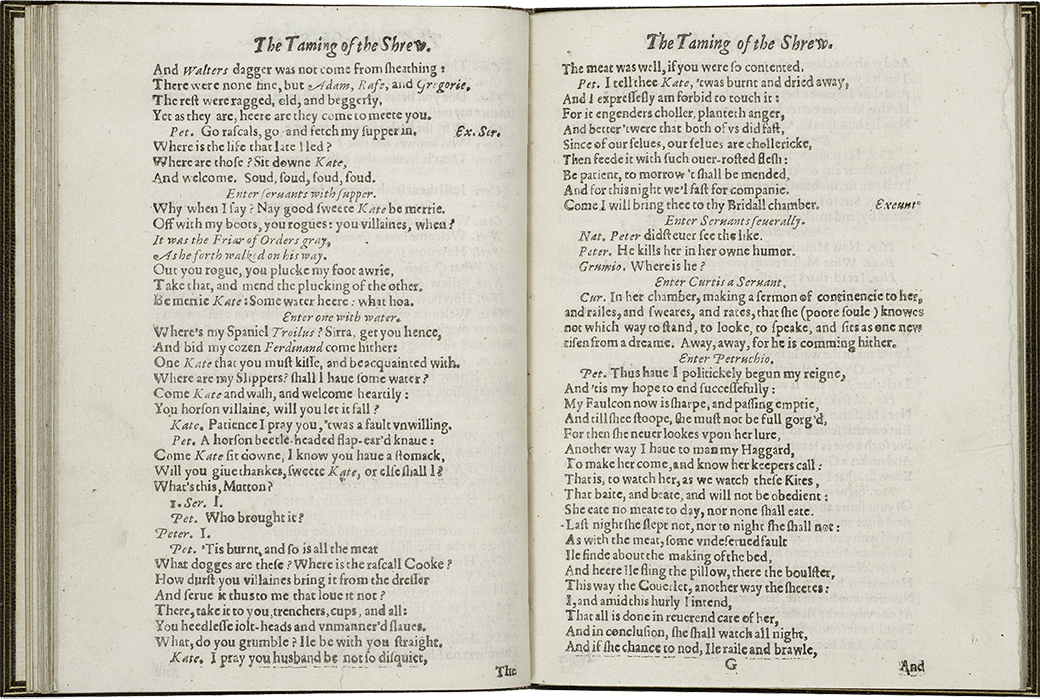

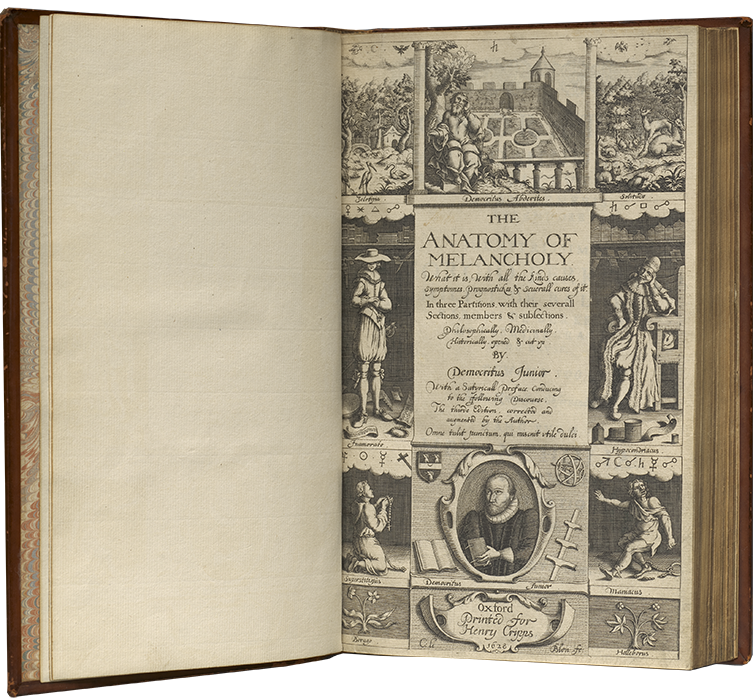

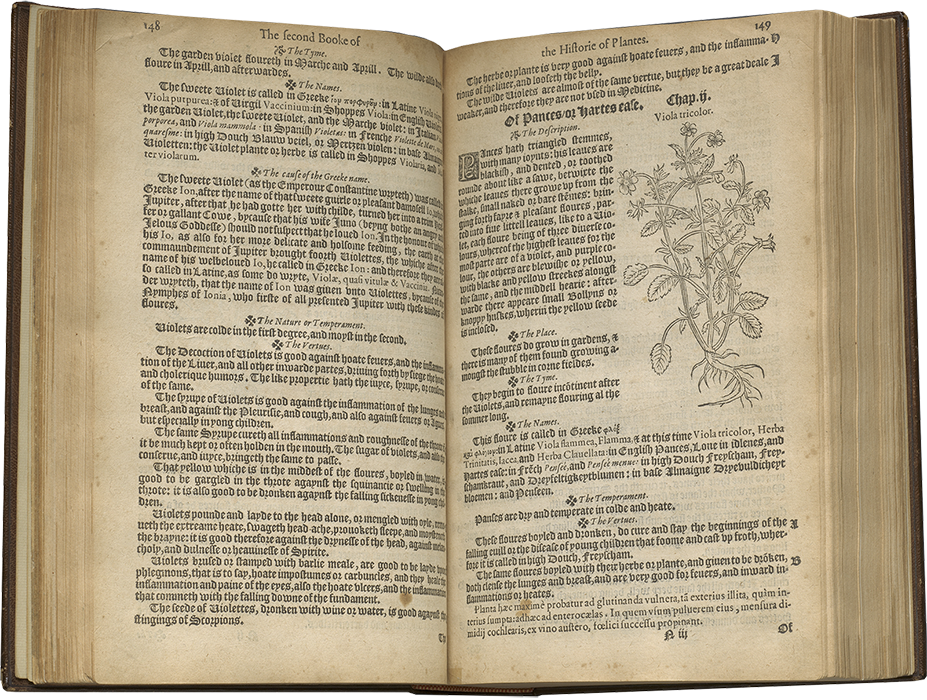

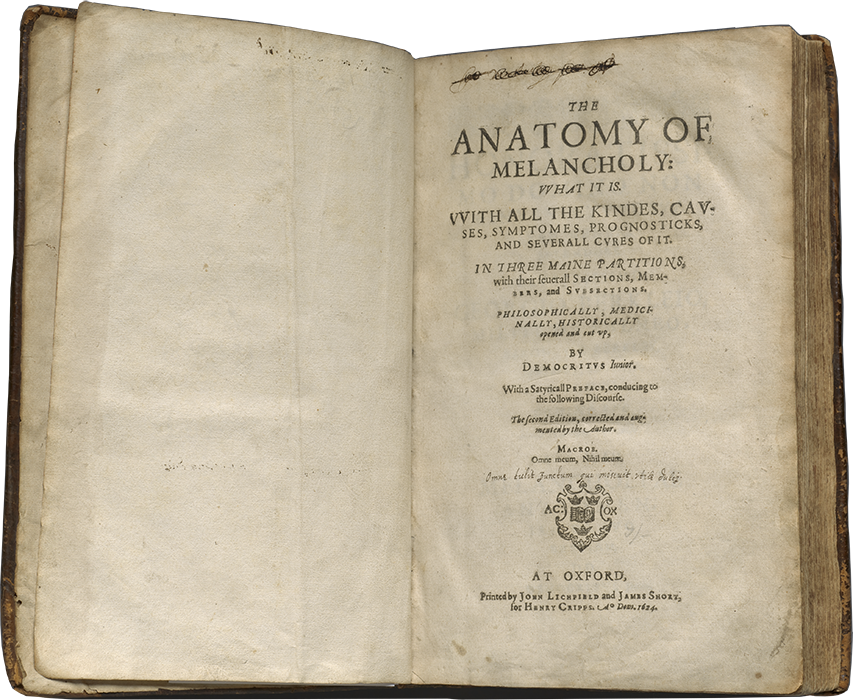

Yet Shakespeare understood human personality in the terms available to his age—that of the now—discarded theory of the four bodily humors—blood, bile, melancholy, and phlegm.

These four humors were understood to define peoples’ physical and mental health, and determined their personality, as well.

The language of the four humors pervades Shakespeare's plays, and their influence is felt above all in a belief that emotional states are physically determined. Carried by the bloodstream, the four humors bred the core passions of anger, grief, hope, and fear—the emotions conveyed so powerfully in Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies.

Today, neuroscientists recognize a connection between Shakespeare's age and our own in the common understanding that the emotions are based in biochemistry and that drugs can be used to alleviate mental suffering.