ExhibitionTransformation of a Monster

From its first appearance in 1818, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein both fascinated and repelled audiences. Her story, moreover, attracted other creative artists, who freely adapted the novel for audiences in England, America, and Europe.

The monster underwent a transformation. From a sensitive, reasoning, and articulate being whose crimes resulted from his mistreatment at the hands of humanity, the creature mutated into a grunting brute, whose violent and cruel nature could only be understood as the product of science daring to usurp the god-like power of creation.

“Frankenstein” came to represent the monster as much as his maker.

- 0 of 0

- ForwardForward

- BackBack

- EnlargeEnlarge Image

- AudioPlay Audio

- DocumentRead Transcript

- FolderFolder

- CarouselCarousel

- Digital GalleryDigital Gallery

- VideoVideo

- View PDFView PDF

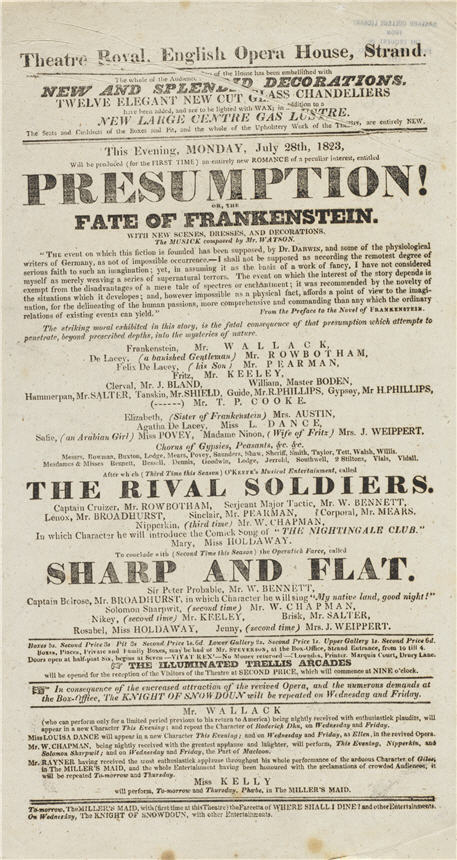

Playbill from Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein, Opening night, July 28, 1823

Courtesy Harvard Theater Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, bpf TCS 63 (English Opera House 1823–1826)

In 1823, Mary Shelley learned from her father about a play called Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein. The playbill advertised the “striking moral exhibited in this story,” namely, the “fatal consequence of that presumption, which attempts to penetrate, beyond prescribed depths, into the mysteries of nature.” Shelley’s novel and its complex story of human ambition and monstrous possibilities had begun a process of simplification (many characters were eliminated) and distortion (the monster becomes a speechless, remorseless killer) that would continue in the centuries to come.

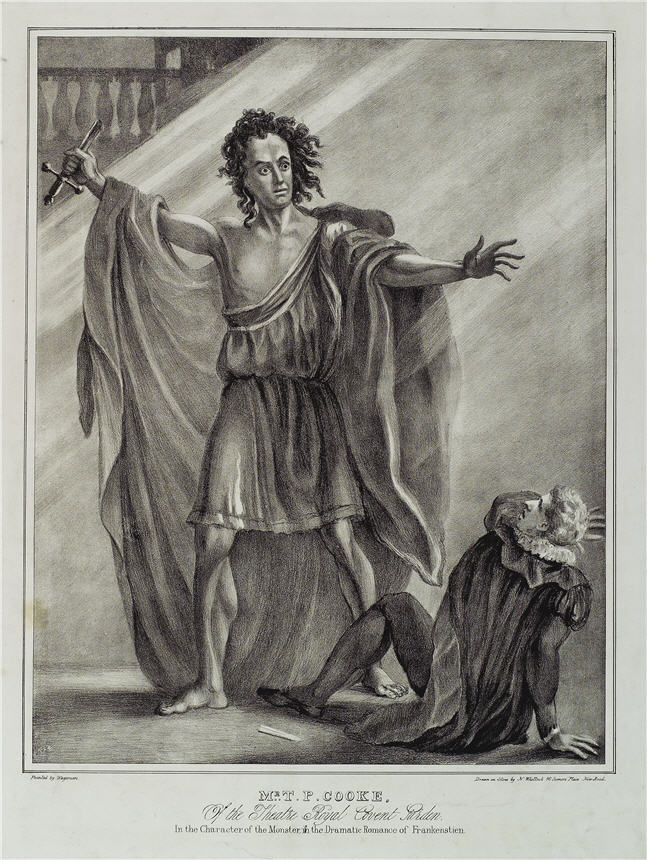

T. P. Cooke as the monster in Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein

Artist: Thomas Charles Wageman (ca. 1787—1863)

Lithographer: Nathaniel Whittock (1791—1860)

Courtesy The Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelly and His Circle, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

The English actor Thomas Potter Cooke played the role of the monster in Presumption. His face was painted green, his lips were stained black, and he wore blue body paint.

Mary Shelley attended a performance of Presumption on August 29, 1823. “The play bill amused me extremely,” she wrote to a friend, “for in the dramatis personae came, _____ by Mr. T. Cooke.” Mary Shelley had not given her monster a name; later, audiences would use the word Frankenstein to refer both to the monster and his maker.

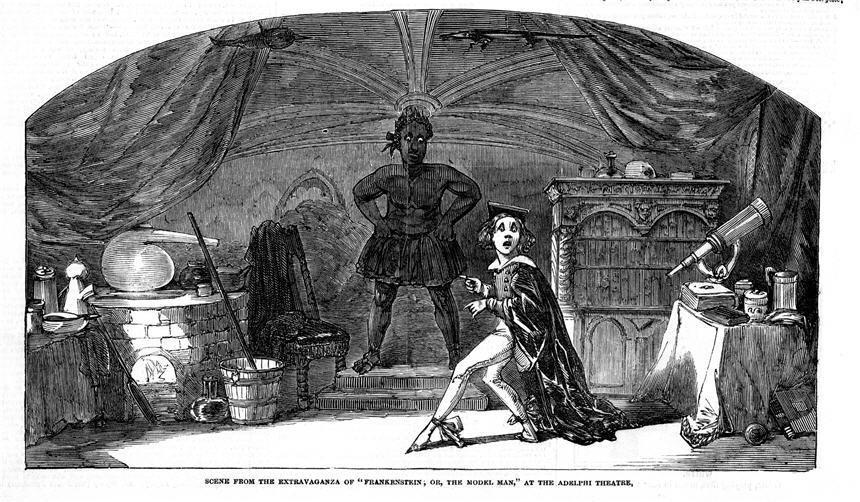

Scene from Frankenstein; or, The Model Man, January 12, 1850

Courtesy University of Massachusetts, Amherst

By the mid-19th century, the popular Frankenstein melodrama had become a subject for parody as in the musical burlesque Frankenstein; or, The Model Man.

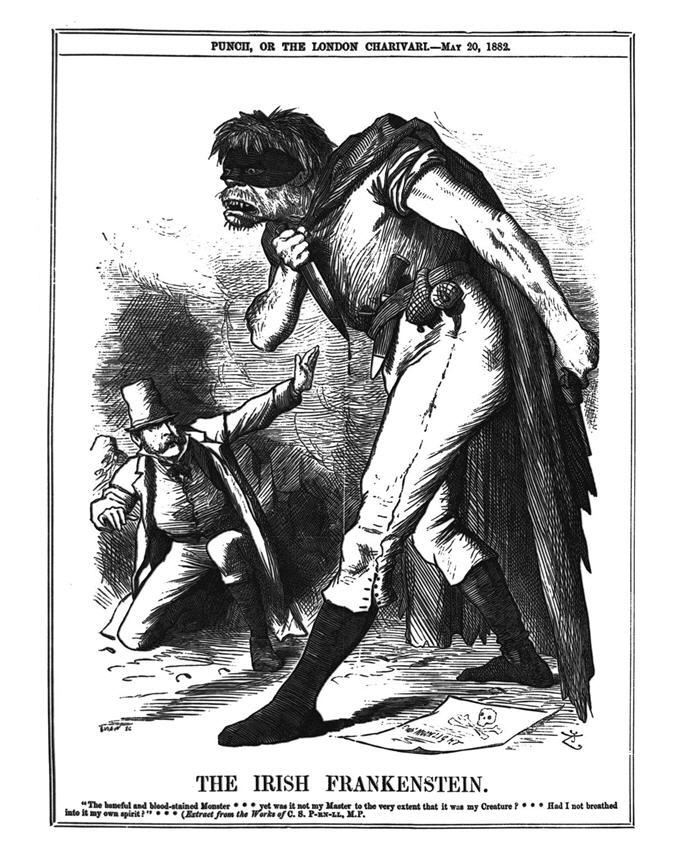

The Irish Frankenstein from Punch, 1882

Illustrator: John Tenniel (1820—1914)

Courtesy Pennsylvania State University Libraries

In the 19th century, the very word “Frankenstein” could be wielded to represent issues and people considered to be out of control. British illustrator John Tenniel depicted the Irish Nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell as the “Irish Frankenstein” for his support of Irish home rule.

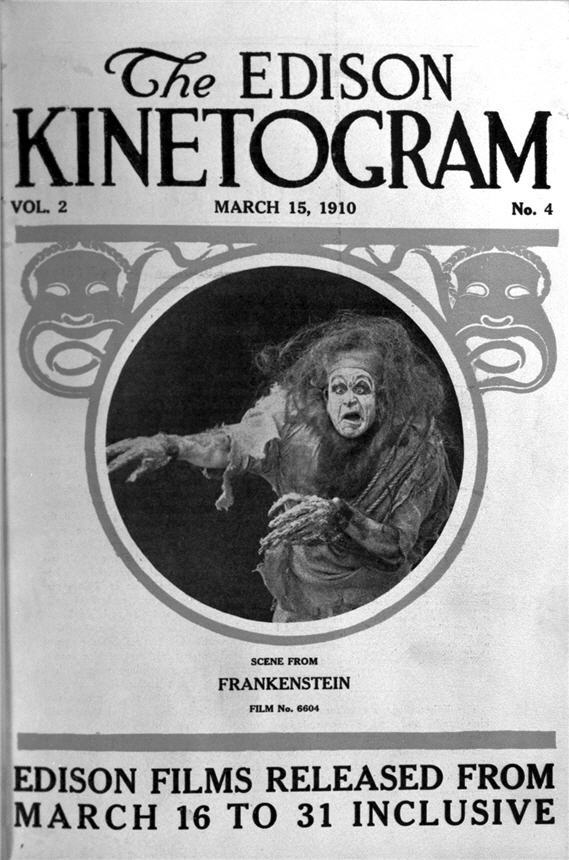

The Edison Kinetogram, March 15, 1910

Courtesy US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Edison National Historic Site

Movies offered a new opportunity for the Frankenstein story to reach larger audiences in the early 20th century. The film company created by inventor Thomas Edison released the first cinematic version of Mary Shelley’s novel in 1910.

The cover of this Edison publication features Charles Stanton Ogle in dramatic white make-up as the monster.

The dismal failure of the film did not deter other filmmakers from taking up the Frankenstein story.

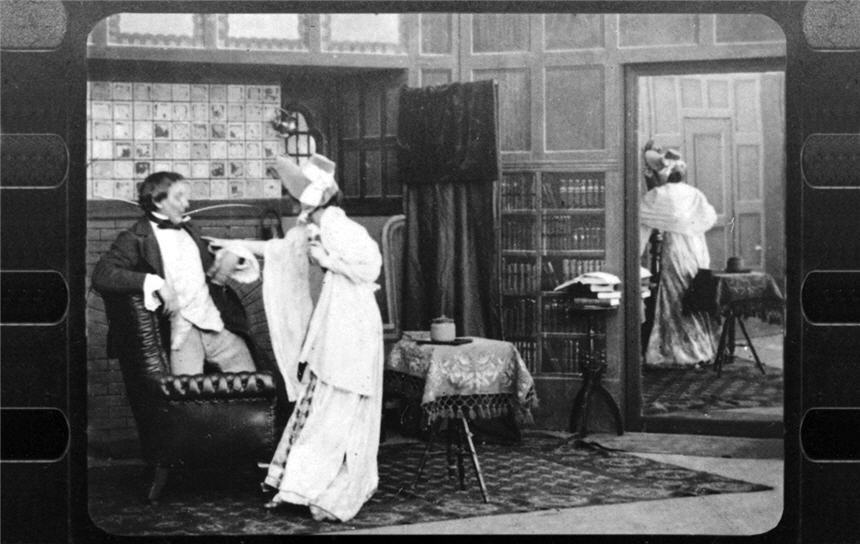

Creation scene from Frankenstein, 1910

Producer: Edison Manufacturing Company

Courtesy Library of Congress

Directed by J. Searle Dawley, the first cinematic Frankenstein monster was created out of a vat of chemicals, rather than by the electrical apparatus associated with later filmic monsters.

-

Film still from Frankenstein, 1910

Producer: Edison Manufacturing Company

Courtesy Library of Congress

In this scene from the 1910 Edison Films Frankenstein, the monster interrupts Dr Frankenstein and his fiancée.

-

Poster for Frankenstein, 1931

Courtesy Universal Studios Licensing LLC

In 1931, Universal Pictures gambled that American audiences would flock to “horror films.” A critical and commercial success, Frankenstein was named one of the top films of the year by The New York Times.

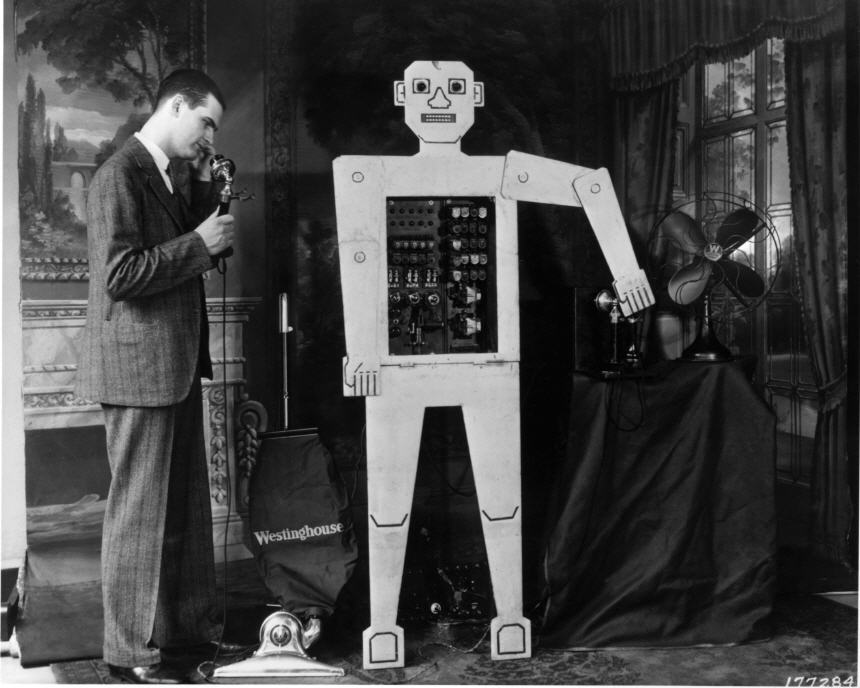

Westinghouse Laboratories’ mechanical man “Televox,” 1928

Courtesy Westinghouse Electric Corporation

In the 1931 Frankenstein film, the monster was characterized by stilted, machine-like movements. To produce this effect, Boris Karloff wore a five-pound metal rod next to his spine. One inspiration for the mechanical motion of the movie monster may have been “Televox,” developed by Westinghouse engineers in the 1920s.