Exhibition: Living Factories

-

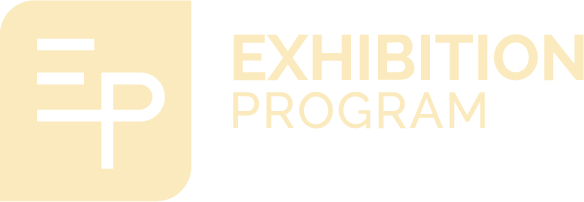

Recovering the diphtheria serum from horse blood in Marburg, Germany, drawn from nature by Fritz Gehrke, 1890s

Courtesy of National Library of Medicine

-

Guinea pigs used for testing serums and toxins at Parke Davis & Company, ca. 1925

Courtesy National Museum of American History

-

Guinea pig room at Parke Davis & Company, ca. 1925

Courtesy National Museum of American History

-

Intubation kit, ca. 1898

Courtesy National Museum of American History

Diphtheria is characterized by a membrane that grows in the throat causing the infected child to struggle for breath. To prevent suffocation, doctors performed tracheotomies and intubation, surgical methods for restoring a breathing passage.

This intubation kit includes a set of seven tubes, sized for children up to age twelve, along with the tools used for inserting and extracting the tubes from the throat.

-

Anti-Diphtheritic Serum and syringes, Parke, Davis & Company, ca. 1898

Courtesy National Museum of American History

Parke Davis was one of the first American companies to manufacture the new serum.

-

“Injecting Diphtheria Antitoxin,” illustration from a Parke Davis publication, 1895

Courtesy The Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia

-

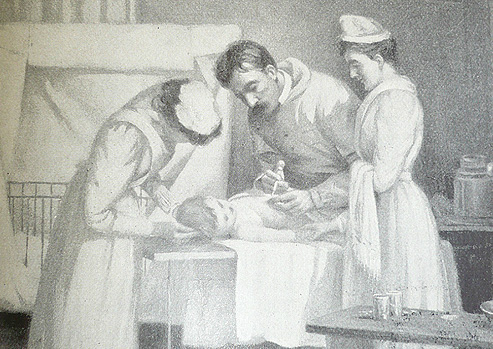

“How New York City’s Health Department Makes Serums and Vaccines for the United States Army,” Popular Science, December 1917

Courtesy Smithsonian Libraries, National Museum of American History

How New York City’s Health Department Makes Serums and Vaccines for the United States Army

Preparing the Bacteria

In the preparation of typhoid vaccine the bacteria are grown in the bottles you see on the table. The germs are killed by pouring a salt solution over them. The bottle on the shelf contains the salt solution which is being siphoned into the bottle containing the colony of typhoid fever germs.

Transferring the Bacilli

Tetanus bacilli occur in dust, earth and manure. They do not grow in the presence of oxygen and are particularly dangerous if they get into deep wounds. The young lady in the photograph is drawing up tetanus bacilli from the bottom of a test tube be means of a glass tube which she holds in her mouth. Thus the germs are transferred from tube to tube.

The Resultant Powerful Toxin

Here the large flask is being inoculated with tetanus bacilli. The small wire basket at the right contains test tubes in which are the tetanus germs. The flame which you see just to the right of the flask which is being inoculated is kept burning so that any instrument may be immediately sterilized after exposure.

The Final Step

The finished product containing millions of dead typhoid fever bacilli is poured by means of a siphon into large bottles. The vaccine is kept in a refrigerator until it is needed for use. Note the milky appearance of the vaccine.

A Glimpse into the “Shop” of the Laboratories

This photograph shows the refrigerator in the Bacteriological Laboratories of the Department of Health of the City of New York, where serums, vaccines and anti-toxins are prepared for the use of the United States Army. Much of this material will be shipped to the front. In the containers and bottles which you see on the shelves is $150,000 worth of material. There is enough diphtheria antitoxin to treat 75,000 men, enough tetanus antitoxin for 200,000 men, enough smallpox vaccine for a half million men and enough antimeningococcus serum to treat 2,500 men suffering from cerebrospinal meningitis.

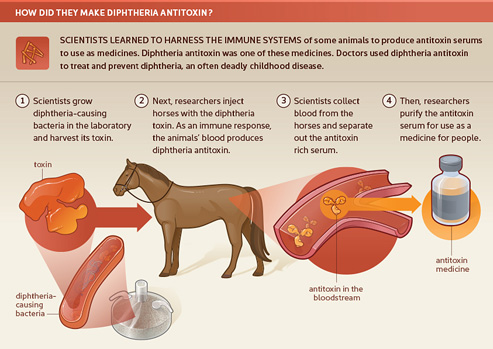

Bleeding the Horse to Obtain the Serum

After the horse has been inoculated with the disease poison in gradually increasing doses he is bled and his serum is found to be antitoxin. This is administered to human beings and renders them immune to the disease. The horses are kept in the pink of condition. At periodic intervals they are given a rest. During the rest periods they are turned out to grass. When thoroughly rested, they are inoculated again. Some horses give more antitoxin serum than others. The same horse may be used at several different times for the preparation of distinctly different antitoxins.

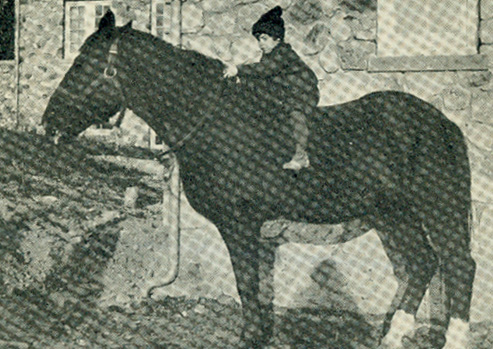

Inoculating a Horse with Toxin

One of the 73 horses in the stables of the Department of Health of the City of New York at Ctisville. This horse is being inoculated with diphtheria toxin. Small doses gradually increased render the horse immune to diphtheria. Horses are used in the preparation of diphtheria, tetanus antitoxin and antimeningococcus serum.

-

Guinea pig holder, early 20th century

Courtesy National Museum of American History

-

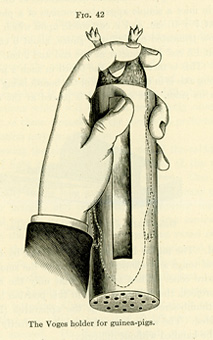

“The Voges holder for guinea-pigs,” from The Principles of Bacteriology by Alexander Crever Abbott, 1899

Courtesy National Museum of American History

This tube was used to immobilize guinea pigs during inoculations. Injections of toxins and serums were administered through the cut-out window. Although their role was less publicized, small mammals, such as the guinea pig, were essential to the serum manufacturing process.

-

Animal Record Card from Hygienic Laboratory Bulletin No. 21, 1905

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Animal Record Card for a guinea pig used in serum and toxin testing. Pig No. 1567 is identified by a rough sketch of its color markings.

TREASURY DEPARTMENT

PUBLIC HEALTH AND MARINE-HOSPITAL SERVICE,

HYGENIC LABORATORY–Form No. 0007ANIMAL RECORD CARD

Subject: Diphtheria Lt

Weight: 250 No. 1567

Operator: MyR

Marks: (female symbol) Own raising

Date: 1-25, 1905, 3pm

t Date: 1-29, 1905, 5pm

.22 02 Tox. *7 + 1 I.E. Ehrlich 15-11-05Autopsy 1-30-05. 10 am

Severe local reaction hemorrhage

-Skin bound down by plastic

exudate. Edema marked, extending to neck.

No fluid in pleuras.

Peritoneum normal.

Adrenals infected and swollen.E.I.

-

Harness and lead for the horse “First Flight” and a bottle of botulism antitoxin, 1970s

Courtesy National Museum of American History

The thoroughbred horse “First Flight” was used to produce serum for botulinum toxin, the deadly bacterial poison often spread through foods. He produced the antitoxin for the U.S. Army from 1978–1993.

-

A photo of Old Faithful in Who’s Who Among the Microbes by William H. Park and Anne W. Williams, 1929

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

“Old Faithful,” was a horse that produced antitoxins for the city of New York in the early twentieth century. A few of the individual horses used for serum production were celebrated for their service to humankind

-

Injecting a horse with diphtheria toxin, New York City Health Department, 1940s

Courtesy Library of Congress

Large animals like horses were essential to produce the quantities of serum needed to supply the population.

-

Animal record book, New York City Department of Health, 1897–1898

Courtesy National Museum of American History

In the 1890s the New York City Department of Health kept a logbook of the horses used for antitoxin production. The entries for each animal provide a record of toxin injections and bleedings, the amount of blood collected and serum produced, and the animal’s death.

Animal No. 7 received 8 toxin injections and was bled for 30,350 c.c. (8.02 gallon) of blood during Novermber 1897&–December 1898.

Animal No. 83 received 11 toxin injections and produced 50,190 c.c. (13.25 gallon) of blood during October 1897&–May 1899.

Animal No. 96 received 6 toxin injections and was bled to produce 26,430 c.c. (6.98 gallon) of blood during October 1897&–January 1899. Among the collected blood, 265 c.c. was noted for use in toxin injections.

Animal No. 111 received 7 toxin injections and was bled to produce 18,480 c.c. (4.88 gallon) of blood during November 1897&–July 1898. The record contains three entries under “Destroyed” column.

Animal No. 115 received 12 toxin injections and produced 39,100 c.c. (10.33 gallon) of blood during December 1897&–December 1898. Two “distroyed” entries are noted as “moldy” and “broken.”

-

![]() Humans and animals have natural defense systems that produce antibodies in the blood to combat bacteria and other harmful substances invading the body. In the late nineteenth century, scientists investigating this immune response in animals developed new methods for treating diseases in humans.

Humans and animals have natural defense systems that produce antibodies in the blood to combat bacteria and other harmful substances invading the body. In the late nineteenth century, scientists investigating this immune response in animals developed new methods for treating diseases in humans.

One of these early therapies used blood serum, collected from animals inoculated with toxins from bacteria. The natural protection these animals developed against the toxin could be passed to humans through injections of the serum. In commercial production, horses and other large animals served as living serum factories to grow the so-called “antitoxins” for human use.

Serum therapy provided an effective cure for diphtheria, an often fatal childhood disease. The demand for serum established a new drug industry that required the use of large numbers of animals for production.