"No tongue can tell, no mind conceive, no pen

portray the horrible sights I witnessed."

Recollections of a soldier wounded at Antietam, 1862

Most soldiers, many of whom were as young as eighteen when they reported for duty, were unprepared for the realities of wartime and the scale of the carnage. They were usually marshaled for service without training, and often stationed miles from where they had grown up. Both sides had predicted a swift resolution to the conflict, and morale plummeted as the fighting dragged on.

Wounds of War

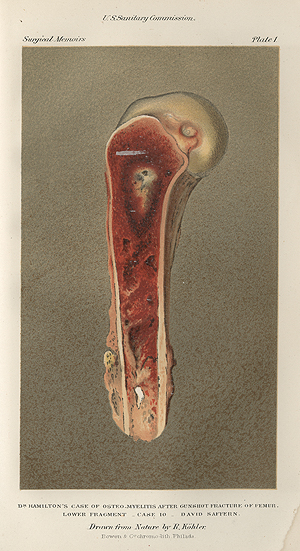

Infection in bullet wound, Surgical Memoirs of the War of the Rebellion, Vol 1, 1870

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

New technologies increased both the risk of injury and its severity to soldiers. Rifled muskets fired farther and more accurately than older weapons and could be quickly reloaded with the minié ball, a bullet of soft lead invented in the 1840s. The ammunition caused extensive damage as it changed shape on impact, shattering two to three inches of bone and dragging skin and clothing into the wound. The scale of the damage and risk of infection was a major cause of amputations.

Union Field Hospital, Savage Station, VA, after the battle of 27 June 1862

Courtesy Library of Congress

Deadly Diseases

Soldiers were vulnerable to infectious diseases that spread rampantly in crowded camp conditions. In fact, yellow fever, smallpox, malaria, and diarrheal diseases took more lives than battlefield injuries. Among those who had not been previously exposed to them, childhood illnesses such as measles, mumps, and diphtheria became a serious threat. Some men never even saw combat, falling so ill as to require immediate hospital care. They perished or recovered alongside the rising numbers of wounded swelling the wards after every battle.

The Cripple,

hospital newspaper, 1864

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

DOWNLOAD THE PDF