Plantation kitchens were chaotic, noisy, smoky, smelly, sweltering, and very dangerous.

The cooking hearth is an enduring image of warmth and well-being. For the enslaved, however, kitchens were anything but comforting.

There was never an idle moment. If the cooking was finished, enslaved workers performed other chores, including watching their own children and those of their white slave owners. Because they labored in the house kitchen, these workers were regularly exposed to the whims of the slave owner and mistress.

Washington’s Kitchen, Mount Vernon, Eastman Johnson, 1864

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Kitchen danger

Preparing tasty meals over an open fire required hard and precise work. Enslaved cooks, such as Lucy and Nathan at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, started work at 4:00 A.M.

Sometimes, people got burned. If cooks unintentionally misgauged fire temperatures, they might destroy food. The changing seasons could spoil meats and turn vegetables to mush.

Mixing bowl, ca. 18th century

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Exhaustingly tasteful

To make biscuits or bread, Lucy Lee, one of George Washington’s enslaved cooks, would leave dough in a large bowl to rise for hours. Later, Lucy would thump the dough, sometimes using the side of a rolling pin, for another hour until it was smooth and elastic.

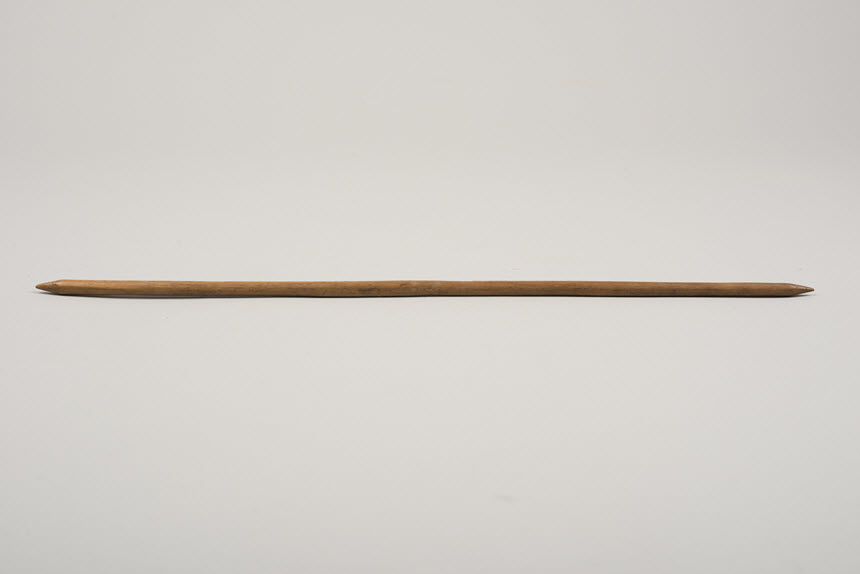

Rolling pin, ca. 18th century

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Exhaustingly tasteful

To make biscuits or bread, Lucy Lee, one of George Washington’s enslaved cooks, would leave dough in a large bowl to rise for hours. Later, Lucy would thump the dough, sometimes using the side of a rolling pin, for another hour until it was smooth and elastic.

Knitting needle, ca. 18th century

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Exhaustingly tasteful

The Washingtons expected Lucy to knit stockings while the dough was rising and the other food simmered over the hearth.

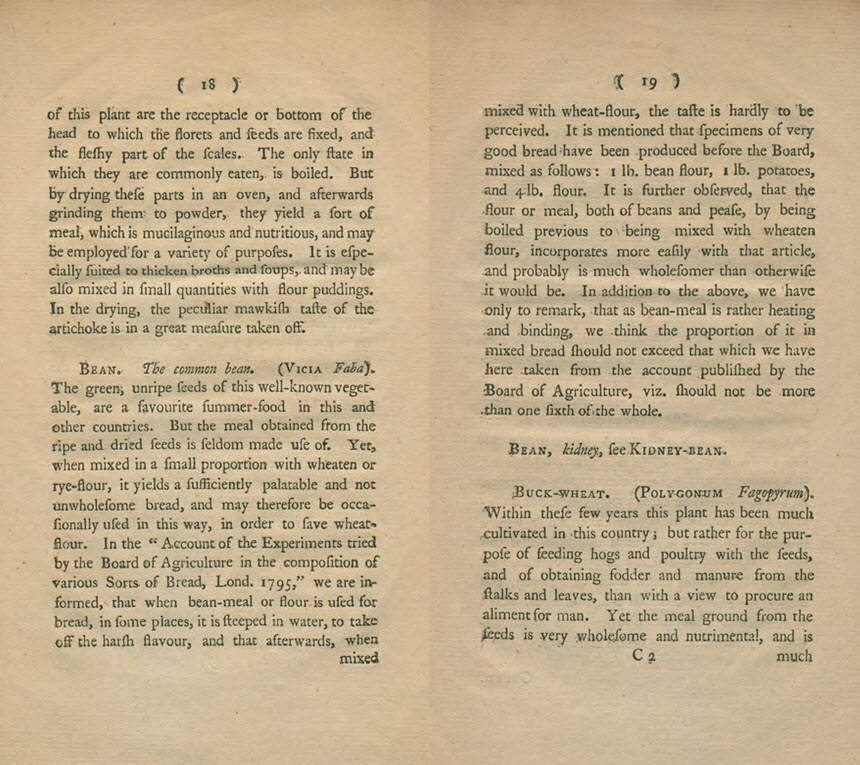

An Enumeration of the Principal Vegetables, and Vegetable Productions, ..., John Winthrop, 1796

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Versatile grain

Buckwheat was one of many crops grown by George Washington. It was favored for its nutritional value. People used dried buckwheat leaves for tea. They ground buckwheat into flour to make griddle and pancakes.

Bowl, ca. 18th century

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Slave Remedies

George or Martha Washington would often summon “Old Doll,” an aged slave to the kitchen to make mint water. The menthol helped to relieve a sore throat, upset stomach, and indigestion.

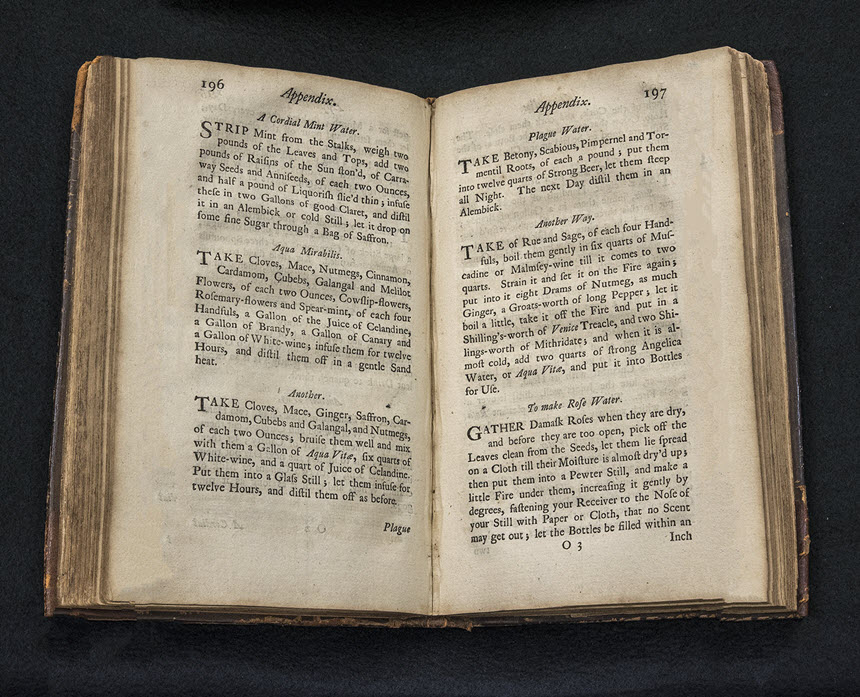

The Compleat City and Country Cook: or, Accomplish’d Housewife..., Charles Carter, 1732

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

A Cordial Mint Water

““Strip mint from the Stalks, weigh two pounds of the Leaves and Tops, add two pounts of Raisins of the Sun flon’d, of Carraway Seeds and Anniseeds…a half a pound of Liquorish flie’d thin; infuse…two Gallons of good Claret, and distil it in an Alembick or cold Still; let it drop on some fine Sugar through a Bag of Saffron”

“Mint” plate from A Curious Herbal, ..., Elizabeth Blackwell, 1737

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Herb lore

Americans at this period relied upon the cultural knowledge of African herbalism as much as they relied upon books about herbs to explain the use of various plants and herbs, such as mint, caraway, and saffron, among others.