Slavery was never benevolent or kind. Despite the realm of opportunities provided a slave, she or he always desired freedom and liberty.

Because of their status on the plantation, some slaves were awarded extra privileges. These privileges may have included the ability to earn income from selling leftover foodstuffs or their own crops in the marketplace; the opportunity to wear fine clothes; and, permission to travel outside the plantation. Despite these advantages, slaves, no matter how revered or “well-treated,” still longed for freedom. Holidays, with relaxed work schedules and absent slaveholders, along with festive events provided opportunities for escape.

George Washington and Family, Thomas Prichard Rossiter, ca. 1858–1860

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Circumventing freedom

During the presidency, the Washingtons repeatedly rotated, albeit illegally, enslaved Africans between their official household in Philadelphia and their Mount Vernon plantation. This circumvented the Gradual Abolition Act, which allowed slaves remaining in Pennsylvania for more than six months to gain their freedom. Rotating them reset the point when the clock on their residency began.

Portrait possibly of Hercules, attributed to Gilbert Stuart, ca. 1795–1797

Courtesy Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza/Scala/Art Resource, NY

From enslaved chef to freedman

Ever aware that he was in bondage, Hercules, considered George Washington’s favorite “capital cook,” longed for freedom. On February 22, 1797, Washington’s 65th birthday, Hercules escaped and was never heard of again.

Shaving razor, 1800–1830

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Cultured and prosperous but still a slave

Like many enslaved house servants, Hercules, a cook for George Washington, sought respectability and integrity by practicing the finest in decorum, proper work habits, and attention to detail, including his personal grooming.

Grease skillet, ca. 18th century

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Withstanding the heat of the hearth

Described as “highly accomplished…proficient in the culinary art as could be found in the United States,” Hercules had the role of overseeing Washington’s kitchens. He would have mastered hearth cooking, knowing the proper amount of oil and lard to fry foods, and how to wield long handled skillets to deftly maneuver hot pans while roasting meats.

Canister, ca. 18th century

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Guarded food

Hercules, one of several enslaved cooks, had the role of overseeing George Washington’s kitchens. He would have used canisters to contain flour, rice, corn meal, and other dry goods to keep out insects and vermin. Foods were closely guarded and carefully rationed.

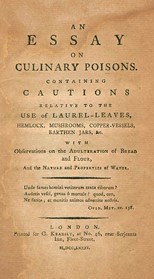

Runaway advertisement for Oney Judge, Philadelphia Gazette, May 24, 1796

Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Using food to escape power

Some slaves took advantage of mealtimes and festive events to provide a distraction in order to “abscond.” According to an 1845 interview, Oney Judge, Martha Washington’s personal servant, left Washington’s house while they were eating dinner.

Sugar bowl with top, ca. 1778

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Sweetness and power

Large meals featured desserts of fruits, nuts, and sweet wines. Such “sweetness and power” often belied the tensions that existed in the dining room. “Invisible” servants, while tending to the comforts of the plantation family, often thought about how they might obtain their freedom.

Tea bowl and saucer, 1779–1782

Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

With power comes leisure

While the Washingtons enjoyed a light repast of bread and leftover meat known as “tea,” the slaves’ day continued. They could not eat until the dining room table had been cleared and cleaned, and tea brewed; wood chopped for the next day; dough kneaded and hoecake batter prepared for breakfast the next morning.

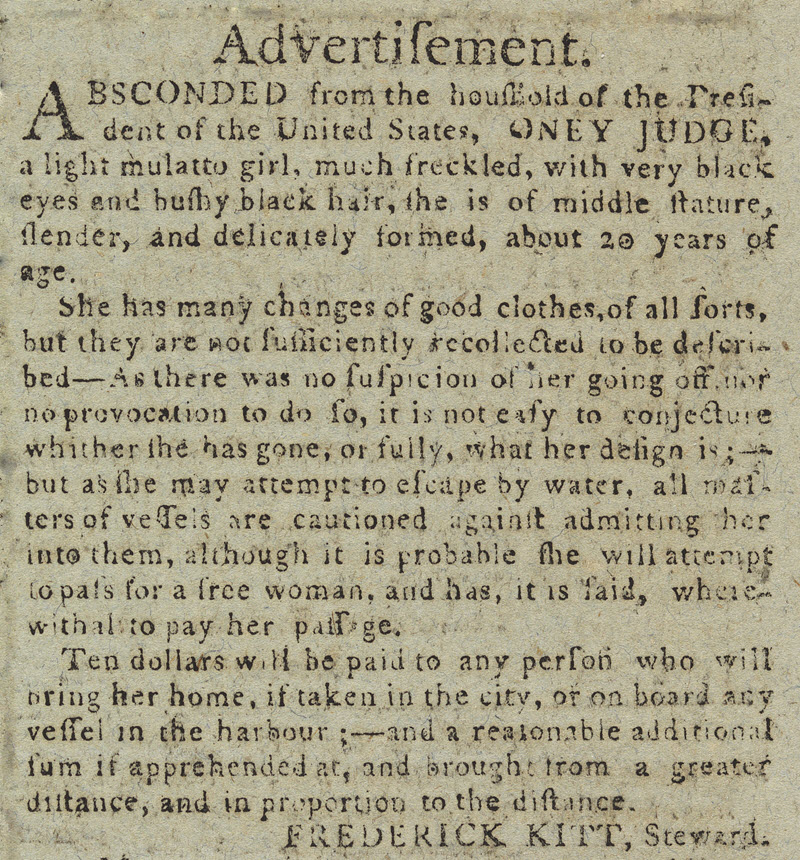

A Treatise on Tobacco, Tea, Coffee, and Chocolate. ..., Simon Paulli, translated by Robert James, 1746

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Taking tea, Tasting freedom

Some slaves earned money to purchase teacups and a teapot or kettle. The social elite viewed taking tea as a necessary social performance. While the Washingtons enjoyed this leisurely ritual, enslaved cooks continued to serve them tea, even as they dreamed of freedom.

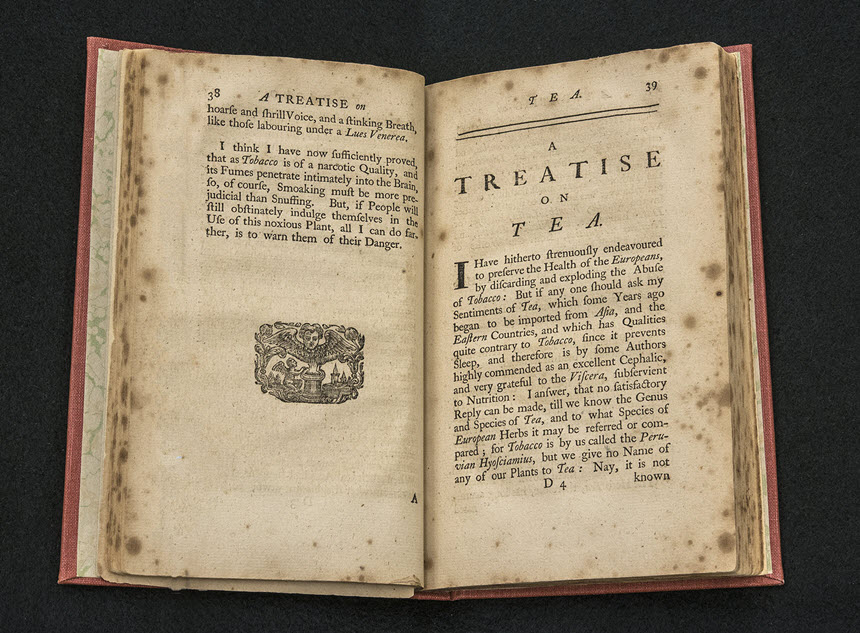

Washington’s Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation, ... , J. M. Toner, 1888

Courtesy National Library of Medicine

Serving their way to freedom

Reportedly, George Washington followed rules of civility and decent behavior at his dinner table and in life.

Male and female house servants studied the comfort and welfare of the Washingtons as much to serve as to avoid punishment. They also needed to be aware should an opportunity arise to take their freedom.