Over the ages, philosophers, theologians, and physicians had accepted insanity disorders within their purview. By the late 18th century, however, the first two had largely withdrawn and physicians, social activists, and the state took responsibility for the care and treatment of the mentally ill. Benjamin Rush, often called “The Father of American Psychiatry,” wrote the first systematic textbook on mental diseases in America entitled, Medical Inquiries and Observations upon Diseases of the Mind, published in Philadelphia in 1812. Psychiatry as a medical discipline came into being during the first years of the 19th century.

Professionalization

The rapidly growing population of the United States during the 19th century, along with an ever increasing number of immigrants, gave rise to the need for provision for the poor, the sick, and the mentally ill. Publicly supported almshouses and hospitals were established and the special needs of the mentally ill led to the era of asylums.

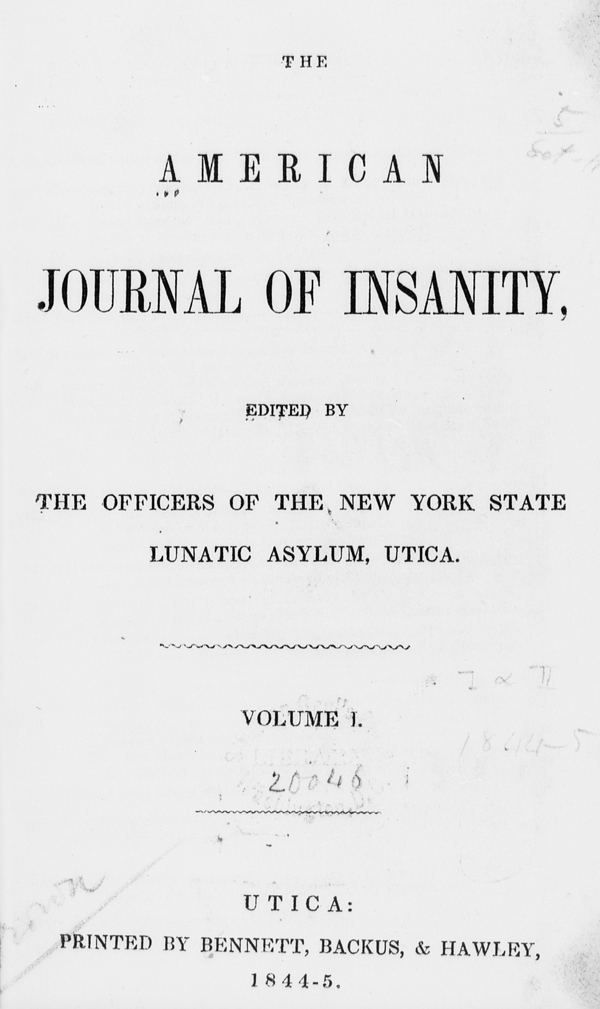

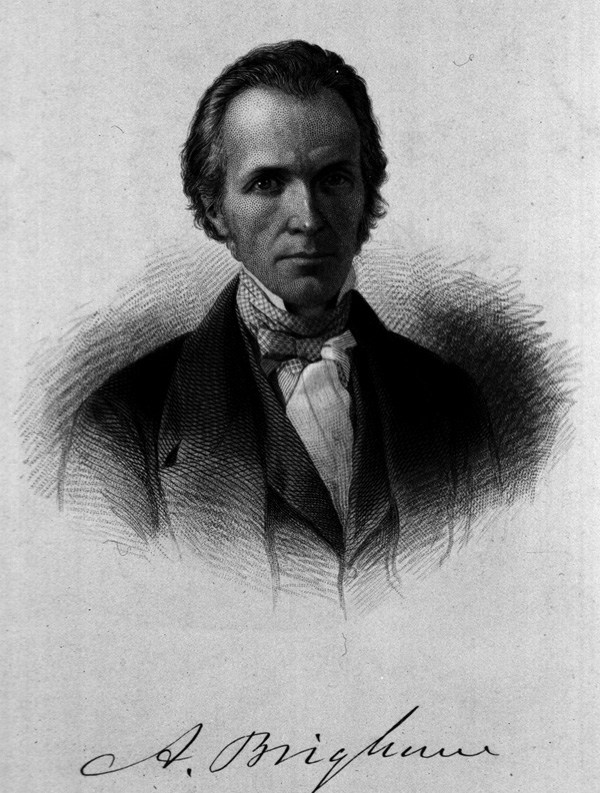

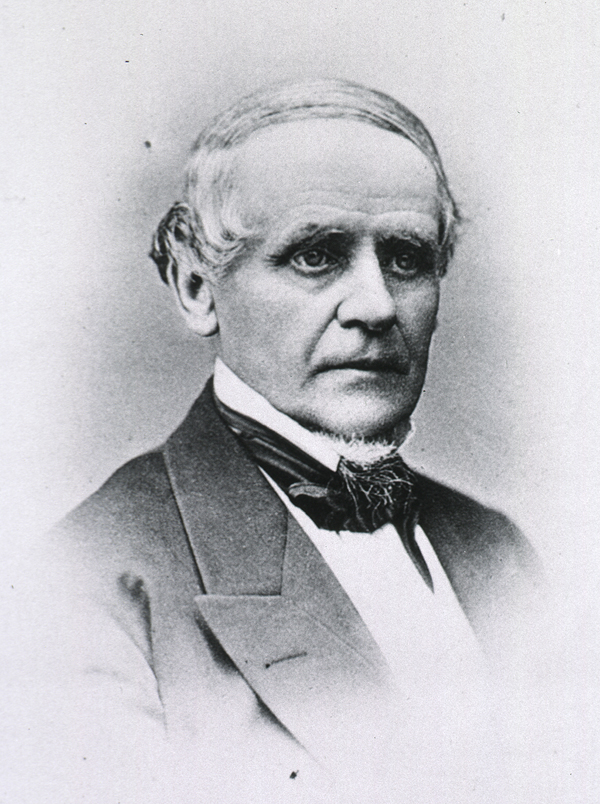

The American Journal of Insanity (AJI) was first published in June, 1844, by Amariah Brigham, Superintendent of the Utica (N.Y.) State Hospital. He was said to have been the author of the entire first issue, which included six articles, a list of existing mental asylums in the U.S., and notes on insanity from France. His aim for The Journal was to acquaint its readers with the nature and varieties of mental illness and with methods of prevention and care for patients.

Amariah Brigham (1798–1849) was born in Marlborough, Massachusetts and received his medical training at the N.Y. College of Physicians and Surgeons. He spent the following year in Europe to further his medical education and returned to Massachusetts in 1829 to establish a practice. In 1840, he became Superintendent of the Hartford Retreat, and in 1842, moved to the Utica State Hospital, the first public mental hospital in New York State.

Brigham had published on mental illness prior to AJI. His book, Remarks on the Influence of Mental Cultivation on Health (Hartford, 1832), went into three editions. He believed that insanity often resulted from ‘moral’ causes such as worries and anxieties. In 1840, he published another monograph, An Inquiry into Diseases and Functions of The Brain, Spinal Cord and Nerves (New-York, 1840).

The AJI remained the property of the Utica State Hospital, though it served as the official publication of the Superintendents' Association (see below). In 1892, the journal was bought by The Association, and in 1921, the name was changed to the present American Journal of Psychiatry by The American Psychiatric Association.

The Superintendents’ Association

By 1844, 25 public and private mental hospitals had been established in the United States. The Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane was organized in Philadelphia in October, 1844 at a meeting of 13 superintendents, making it the first professional medical specialty organization in the U.S. The objectives of the Association were “to communicate their experiences to each other, cooperate in collecting statistical information relating to insanity, and assist each other in improving the treatment of the insane.” The name of the organization was changed in 1892 to The American Medico-Psychological Association to allow assistant physicians working in mental hospitals to become members. In 1921, the name was changed to the present American Psychiatric Association (APA).

The American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) was organized in 1847 in Philadelphia through the efforts of Nathan Davis and Nathaniel Chapman primarily to deal with the lack of regulations and standards in medical education and medical practice. Some mental hospital superintendents became active members. Cordial relations between the two groups continued, and members of each attended the others’ meetings.

In 1854, the AMA established a Committee on Insanity which ended in 1867, when a psychology section was organized. Merger of the AMA and the Superintendents’ Association was considered frequently over the years. In 1871, the Superintendents' Association delegated Dr. John Curwen to attend the AMA meeting in San Francisco and explain The Association's rejection of the invitation to a merger. The reasons were that the Superintendents held their annual meeting in a venue where an asylum was located both to assure citizen interest in the care of the insane and to allow the superintendents to visit the asylum. Also, the Association’s meetings were devoted solely to topics relating to the care of the insane, an area of limited interest to general practitioners, and the Association included only psychiatric hospital superintendents.

Over the years, the relationship between the two organizations has waxed and waned. In the 21st century, the APA is an active participant in AMA activities.

Influences

Psychiatry in the 19th century was based primarily in mental hospitals. The later-organized profession of neurology claimed a role in treating mentally disordered people usually on an outpatient basis. While relations between psychiatry and neurology have waxed and waned during the subsequent years, by the end of the 20th century medical advances have brought the two together in a new field of neuroscience.

The Neurologists: S. Weir Mitchell, and The Superintendents' Association

The American Neurological Association, organized in 1875, grew out of the Civil War experiences of physicians who had been involved in caring for soldiers with traumatic injuries of the brain and nerves. The neurologists were mainly in private practice and considered mental illness within their purview because the brain was involved. Relations between the neurologists and the Superintendents' Association were marked by mistrust and hostility. Believing that the asylums were mismanaged and providing inadequate care to patients, in some places, the neurologists called on state legislatures to investigate the asylums.

In 1894, to mark the 50th anniversary of its founding, The Superintendents' Association invited Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a prominent Philadelphia neurologist to address the annual meeting. After querying a number of his colleagues, Dr. Mitchell delivered a scathing address to the superintendents. He said that they had isolated themselves from medicine and they sought no new scientific information through their work, their medical records were inadequate, and their educational efforts among the profession were minimal. The superintendents made little reply to the address. (See: S. W. Mitchell, "Address before the fiftieth annual meeting of the American Medico-Psychological Association, "Proceedings of the American Medico-Psychological Association, 1894, v. 1, pp. 101-121).

In 1897, Dr. Bernard Sachs, a New York neurologist, was invited to address the Association's annual meeting. He gave a placating speech saying that both professional groups should be working together in the interest of patients.

European Influences on American Psychiatry

American asylums were influenced by visits of their superintendents and others to European hospitals. In 1832, Dr. James MacDonald visited Great Britain, France, and Ireland at the request of The New York Hospital prior to the construction of the Bloomingdale Asylum. In 1846, Dr. Luther Bell, Superintendent of McLean (Mass.) Hospital undertook a European trip at the request of the Board planning Butler Hospital in Rhode Island. In 1863, Dr. Tilden Brown visited western European hospitals for the Trustees planning The Sheppard Asylum in Baltimore.

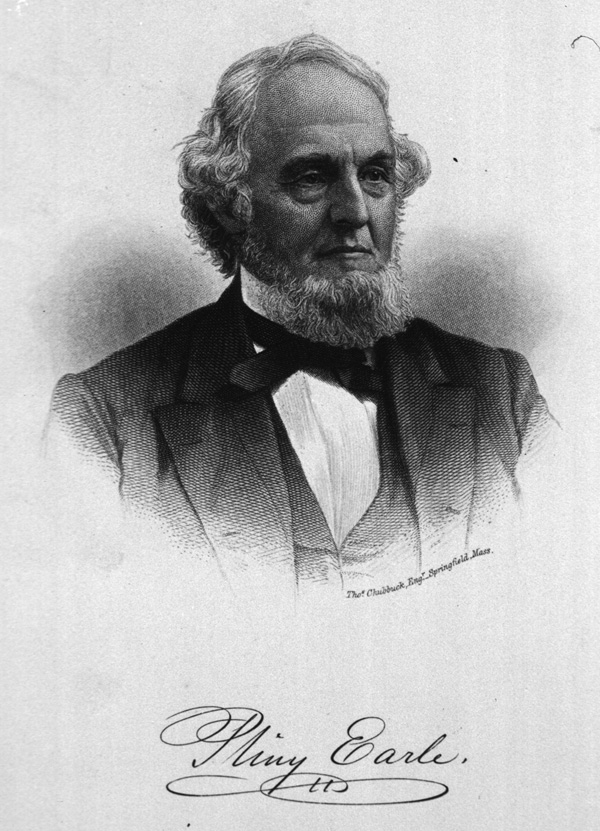

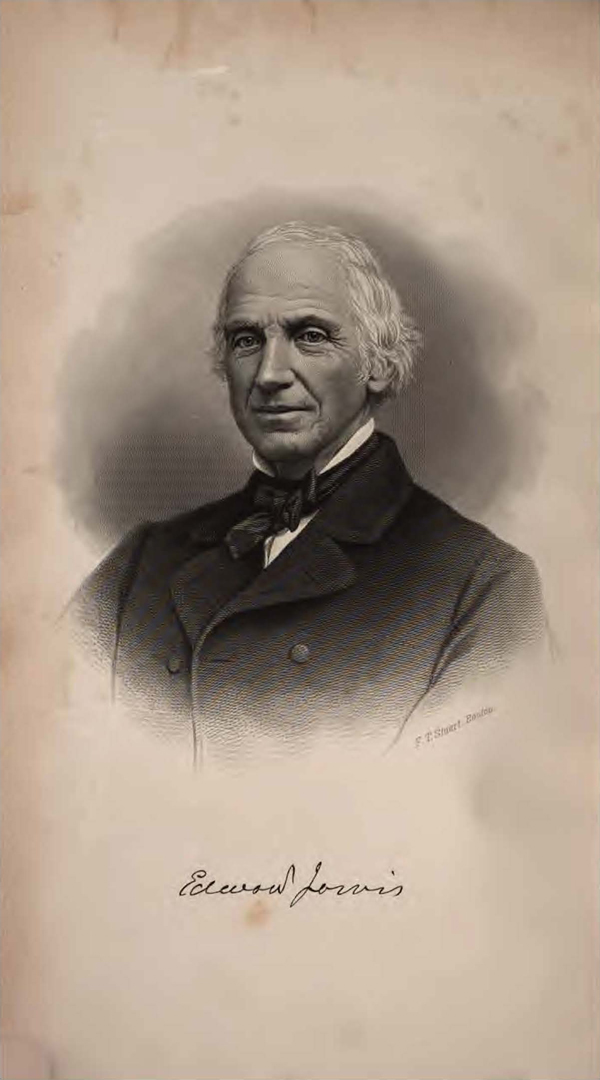

Dr. Pliny Earle, superintendent of several asylums, visited extensively in Europe in 1841 and 1852, publishing reports in The AJI. He also wrote of the German approval to separate 'curable' from 'incurable' patients, a subject debated by the Superintendents' Association during the latter 19th century. Dr. George W. Cook of Canandaigua visited hospitals in England in 1854. In 1860, Dr. Edward Jarvis reported on his visit to English hospital to examine training and employment for patients. In 1868, Dr. Abner Otis Kellogg observed the use of mechanical restraint in European hospitals. Dr. Edward Bruch was impressed by the meager use of restraint in hospitals in England and Scotland.

Books and journals dealing with insanity were regularly reviewed and quoted in The AJI, especially those from Great Britain, France, and Germany. Together with the reports of the travels of the American psychiatrists, they served as an important source of education and influence on practice.

Activism

Dorothea Lynde Dix: Lay Advocacy for the Mentally Ill

Dorothea Dix (1802–1887), a school teacher, was the foremost advocate for the humane care of the mentally ill during the 19th century. Her efforts are credited with the establishment of 32 state mental hospitals throughout the United States.

In 1841, Miss Dix visited a Boston jail to teach a Sunday School class. There she found mentally ill people confined under inhumane conditions. She embarked on a lifelong journey to advocate and procure help for the mentally ill. Her methods included personal visits to jails, almshouses, hospitals, and wherever they were confined, and she carefully documented her findings. She used the interest and influence of prominent citizens and legislators to introduce written "memorials" into state legislatures in which she described the conditions she found, the first being in Massachusetts in 1843. The memorials often led to funds being appropriated to improve or establish mental hospitals.

By 1850, Miss Dix had aroused sufficient public support for her endeavors, and bills were introduced into the Congress for federal lands to be apportioned to the states whose sale would provide funds to create or support facilities for the mentally ill. The bill passed in both Houses of Congress in 1851 but was vetoed by President Franklin Pierce on the basis that the care of the mentally ill was a state, not federal, responsibility.

Miss Dix also visited mental establishments in Great Britain, Ireland, and the European mainland, including visits with the Pope. She exerted influence wherever she went in publicizing conditions of care for the mentally ill and advocating for improved care.

She spent her final years as a resident guest at The Trenton State Hospital in New Jersey, a psychiatric hospital founded through her efforts.

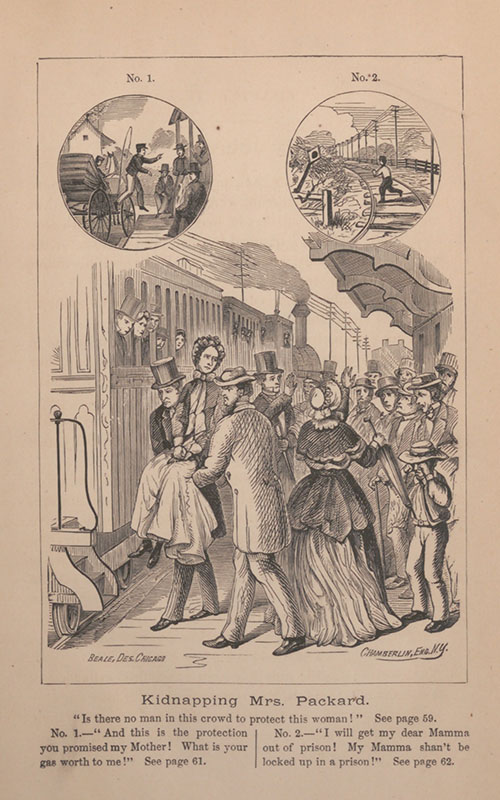

The Case of Mrs. Packard and Legal Commitment

The Superintendents' Association had been involved from its beginning with the rights and protection of patients in civil and criminal matters. In 1868, the Association approved Dr. Pliny Earle's "Project of a Law," which set forth principles for commitment, or coercive admission to a mental hospital as a legal procedure.

In 1860, Elizabeth Packard, who differed with the theology of her clergyman husband, was forcibly placed in an Illinois state hospital. She remained there for 3 years. At that time, Illinois law stated that "married" women could be hospitalized at a husband's request without the evidence required in other cases. Mrs. Packard was able to obtain a release by an action of the hospital, but on her return home, she was locked up by her husband who planned for her admission to an asylum in her native Massachusetts. She eventually gained her freedom in 1863 through a habeas corpus hearing in a local court.

Mrs. Packard then embarked on a vigorous campaign to protect women's rights. She published three books on her asylum experience and that of other women, including The Prisoners' Hidden Life (Chicago, 1868) and Modern Persecution, or Insane Asylums Unveiled (Hartford, 1873). She aroused sufficient public interest and support that a group of influential citizens and social reformers organized in 1880 The National Association for the Protection of the Insane and the Prevention of Insanity. The unremitting antagonism of The Superintendents' Association helped to bring about the demise of the organization within a few years.

In 1869, the Illinois legislature passed a law requiring a jury trial before a person could be committed, a law which remained in effect for 25 years. Iowa enacted a similar law in 1872, and other states took steps to safeguard patient rights. The Superintendents' Association strongly opposed jury trials, on the grounds that it was harmful to patients and professional opinions might be discounted.

The AJI, in an unsigned editorial (presumably) written by Dr. John P. Gray of Utica, wrote, "This fascinating woman… by her feminine wiles had bewitched a whole legislature."

Women in Psychiatry

Women in 19th-Century American Psychiatry

Women were not welcomed into the medical profession during the first half of the 19th century: medical schools did not admit them. Elizabeth Blackwell was the first American woman to gain admission to a medical school and graduated from Geneva (N.Y.) Medical College in 1847. She spearheaded the push for women to enter medicine. With the support of women and some men, 17 medical schools for women were established but after some 50 years all but The Women's Medical College in Philadelphia closed, as all-male medical schools in Michigan, Iowa, Indiana, and elsewhere began opening their doors to a small number of women towards the end of the century.

Many arguments against women becoming physicians were physiological and neurological: would the education and training required make a woman unfit for her "primary duty," childbirth? And was rest (physical and mental) necessary during menstruation? In 1876, noted physician Mary Putnam Jacobi undertook a study undertook a study of women's physiology, and specifically blood pressure, during menstruation, proving that menstruation posed no physical constraints on women. She entered her paper on the subject for the Boylston Prize at Harvard University anonymously and won it, much to the chagrin of many opponents to women's medical education.

Psychiatry in the 19th century was based in the mental hospitals. The asylum superintendents voiced divided opinions about employing women doctors. Dr. John Gray of Utica, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride in Philadelphia, and Dr. John Chapin of Willard (N.Y.) wrote letters to their governors opposing the employment of women physicians, but legislatures especially in New York and Pennsylvania mandated they do so. Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, in his 1894 address at The Association meeting, had urged that women take care of women patients. But discrimination prevailed. Women doctors in many institutions received less pay than their male counterparts performing the same work. They were denied promotions and received little recognition, and as a result many did not remain long at the hospitals.

The earliest record of employment of a woman physician in an asylum was in 1869, when Worcester (Mass.) State Hospital hired Dr. Mary Stinson. Iowa followed in 1873, as did Michigan and hospitals elsewhere. Dr. Alice Bennett, M.D., (also the first woman to receive a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania), remained at Norristown, Pennsylvania for 12 years in charge of the women's division, from 1880 to 1892. Gradually, as more women entered medicine, they were employed at state hospitals. Not until after WWII did the numbers of women physicians increase significantly, however. Eventually, psychiatry became a specialty of choice for many women, and a large number of them entered private practice.

Psychiatric Debates

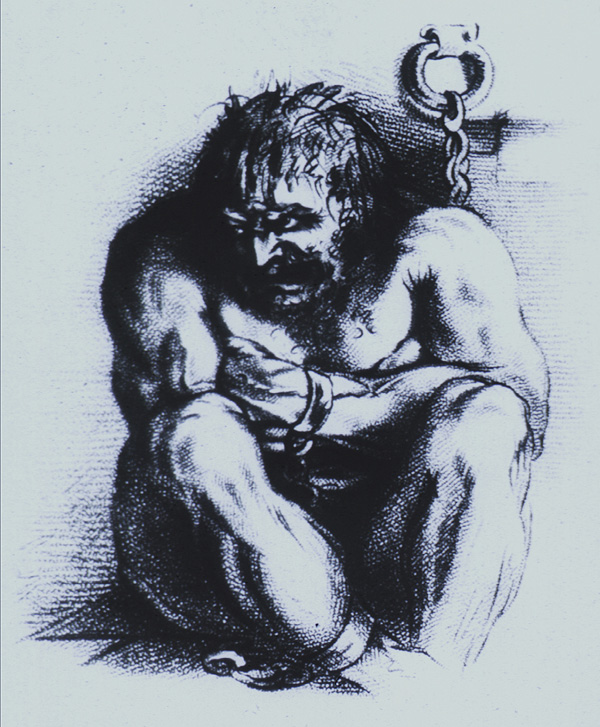

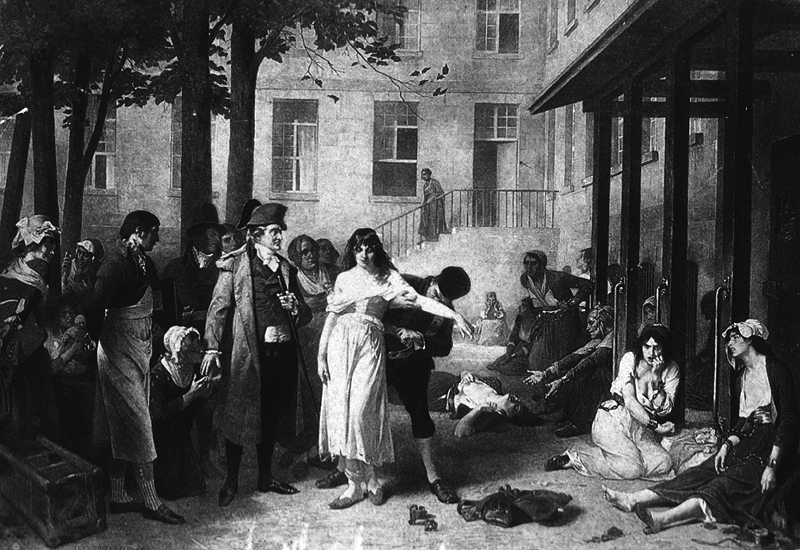

The Question of Patient Restraint

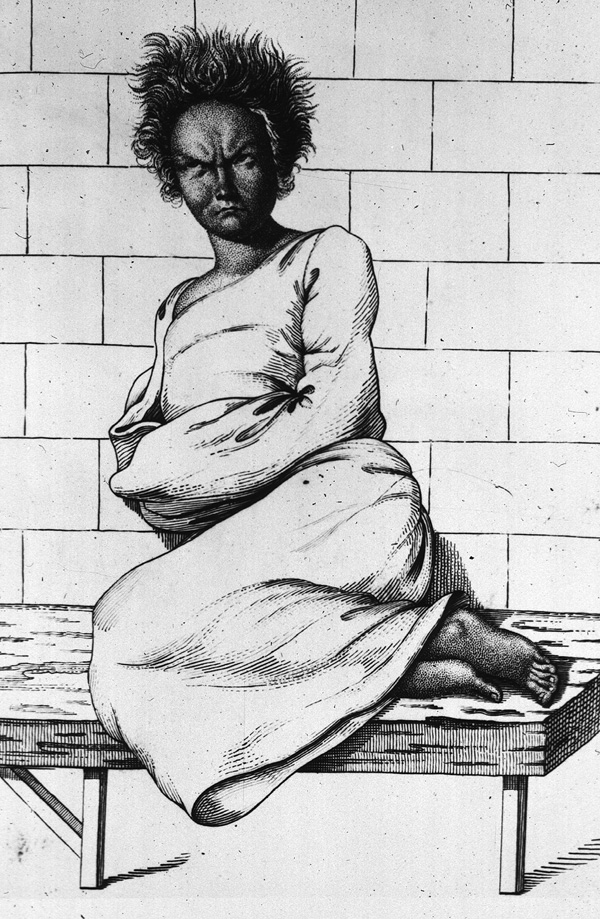

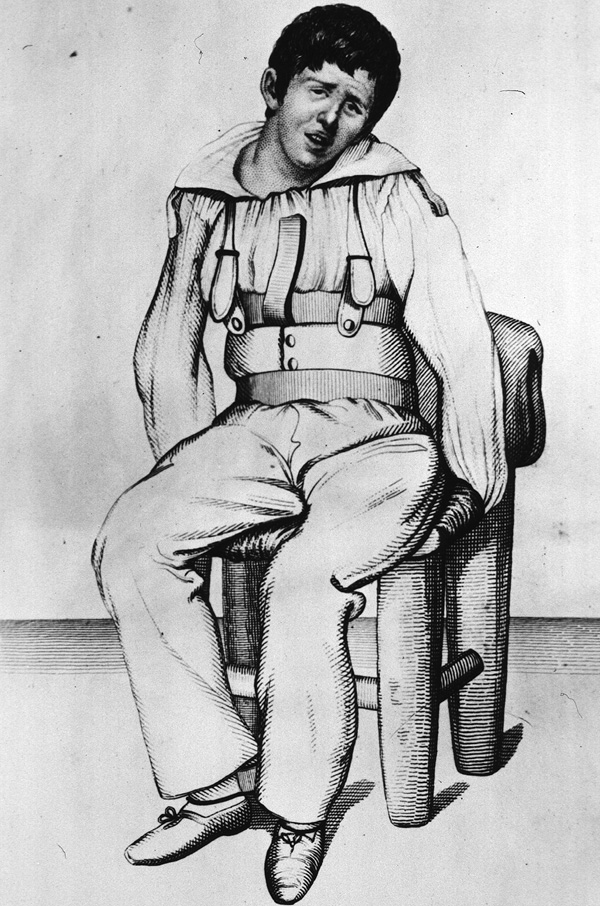

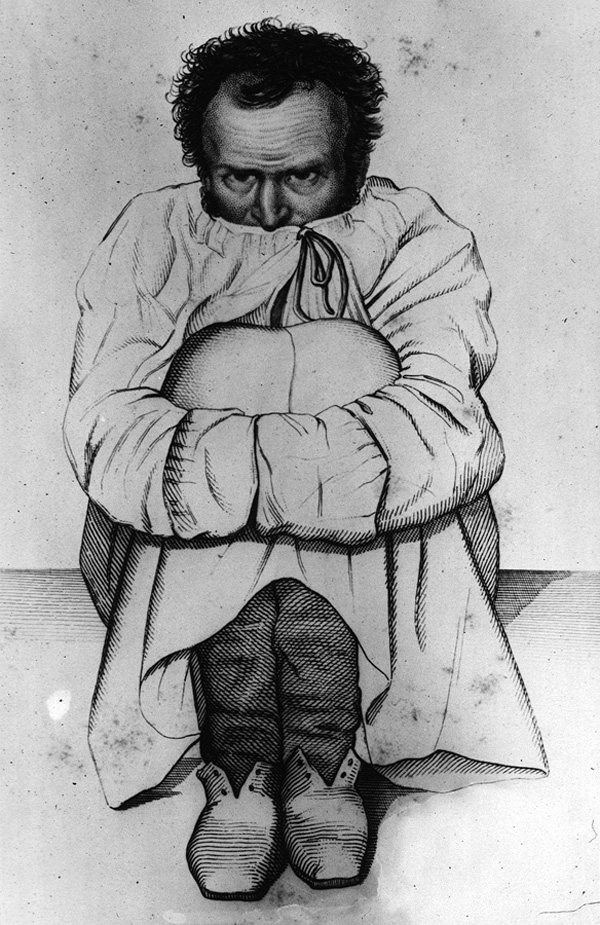

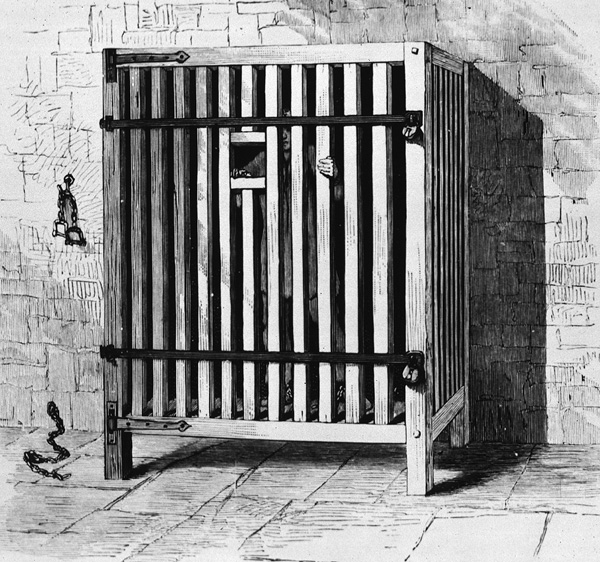

In 1793, Philippe Pinel dramatically struck the chains binding the lunatic women in the Parisian asylum, Hôpital de Bicêtre, and in 1792, the Quaker York Retreat in England began using moral treatment without restraints. In the early 19th-century, Dr. John Conolly, Superintendent of the Asylum in Hanwell, England promoted a non-restraint policy but used patient reclusion and attendants to 'hold' violent patients.

From the beginning, the American Superintendents believed that mechanical restraint was necessary in their hospitals, but it was to be employed at a minimum and never as punishment. But early on Dr. Amariah Brigham employed a cage-like “crib bed” at Utica designed after a European model, and thereafter restraint of one sort or another was used in American institutions well into the 20th century.

In 1875, Dr. (Lord) John Bucknill, a British asylum superintendent, visited ten American asylums. He disagreed with the Superintendents about the use of mechanical restraints, writing that Americans overused restraint despite their highest motives of humanity in his pamphlet, Notes on Asylums for the Insane in America (London, 1876).

The question of mechanical restraint, later supplemented by chemical restraint (drugs), is ongoing, and in recent years government involvement at federal and state legislative and regulatory levels has come into play.

The Dilemma of the Chronic Patient

As the population of the country increased during the latter half of the 19th century, augmented by the entry of thousands of immigrants, the need for beds in the asylums grew sharply. The early superintendents had fixed the size of the asylum to 250 beds so that each patient would be known by the superintendent. By 1866, they had raised the number of beds to 600.

The early optimism about the curability of mental illness gave way as many patients proved to be in need of continuing care. Some European countries, such as Prussia, had placed long-stay patients in separate chronic hospitals which cost less to operate. Debate arose among legislators, superintendents, and hospital boards as to what better pattern of hospital care should be adopted- and economics influenced the debate. The superintendents were strongly opposed to segregation of the chronic patients believing that all patients should have treatment rather than mere custodial care.

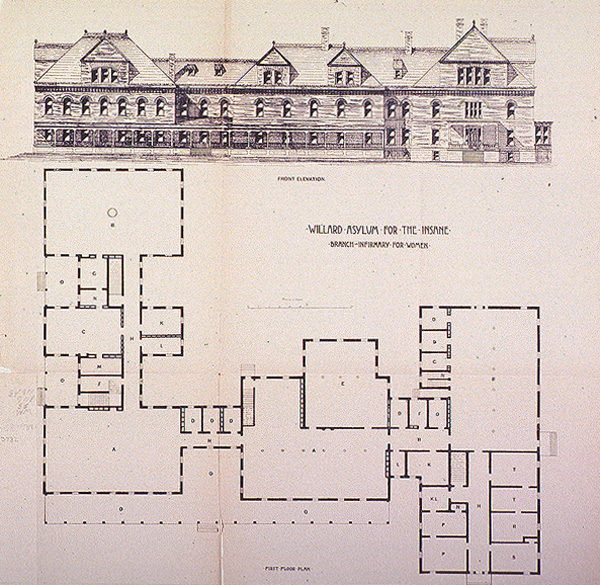

In 1865, the New York legislature authorized the building of a 1500 bed hospital in Willard, near Utica, which opened in 1869 to receive transfers of long stay patients from other state hospitals. By 1875, Willard housed 1000 patients. The superintendents continued their strong opposition to segregation of chronic care, and before long Willard began to admit acute patients as well. The solution for the state hospitals was to build “cottages,” smaller residential buildings on their grounds to transfer long stay patients from the active treatment wards.

In 1954, Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island, N.Y. had a population over 13,000 patients. In 1999, the hospital grounds contained 99 buildings, many of which had housed patients.

A few states adopted the European plan and built small county hospitals to receive long stay patients from the state hospitals. Wisconsin maintained this plan well into the 20th century.

About Diseases of Mind

This content of this site was written in 2006 by Lucy Ozarin, M.D., a Special Volunteer in the History of Medicine Division, with assistance from Michael North, Head of Rare Books and Early Manuscripts.

This site was designed by Astriata, LLC.

You can view the original website, including the full credits for the project, archived in the NLM Institutional Archives web collection.

Note: Unless otherwise noted, all image files are from the Images in the History of Medicine; title pages and texts were scanned from NLM Collections. If you have information regarding the copyright owner, please contact us at NLM Support Center.

Timeline of Early Psychiatric Hospitals & Asylums

Timeline of Early Psychiatric Hospitals & Asylums

Biographies: 19th-Century Psychiatrists of Note

Biographies: 19th-Century Psychiatrists of Note

Books, Exhibitions, and Other Resources from NLM

Books, Exhibitions, and Other Resources from NLM