African Americans, free and enslaved, provided care for wounded soldiers in Union and some Confederate hospitals. The survival of the military hospital was dependent upon their work. Employed in white-only and black-only facilities, African Americans were able to move beyond the confines of private employment to a more public environment. Hospital work represented change and opportunity for many African Americans.

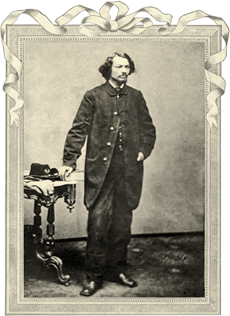

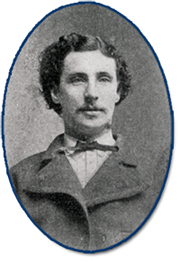

John H. Rapier, Jr., c. 1864

Courtesy Anne Straith Jamieson Fonds,

The J. J. Talman Regional Collection,

The University of Western Ontario Archives

John H. Rapier, Jr. served as acting assistant surgeon in Freedmen's Hospital from 1864 through 1865. Freeborn in Alabama, Rapier received his medical education at Keokuk Medical College in Iowa. In a letter to his uncle in August 1864, Rapier described his life as a surgeon at Freedmen's Hospital.

This typical tented hospital ward was part of Smoketown Hospital, Antietam, Maryland, 1863

Courtesy Edward G. Miner Library, University of Rochester Medical Center and Robert Zeller

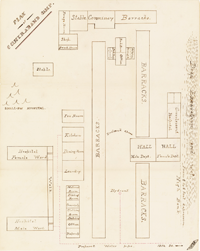

Lithograph of Campbell Army Hospital, later known as Freedmen's Hospital, published by Charles Magnus, c. 1864

Courtesy Historical Society of Washington, D.C.

Contraband Hospital, in Washington, D.C., a black-only facility, treated thousands of former slaves and black soldiers. The hospital hired nurses primarily from within the population of fugitive slaves and employed the largest number of black surgeons among U.S. military hospitals. Contraband Hospital was one of the few medical facilities in Washington, D.C. to treat African Americans and broke the color barrier when it appointed Alexander T. Augusta surgeon-in-charge in May 1863.

Diagram of Contraband Camp, 1863

Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Contraband Camp and Hospital consisted of tents and wooden barracks that served as hospital wards and temporary housing for fugitive slaves.

Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, the largest Confederate hospital, relied on the slaves of local plantation owners and hospital surgeons to fill positions such as nurses, cooks, and laundresses. With over 5000 beds in 150 buildings and tents, Chimborazo treated over 77,000 patients during the war. After the fall of Richmond in 1865, it became a hospital for black Union soldiers.

James Brown McCaw was the chief administrator and surgeon-in-charge of Chimborazo Hospital during the Civil War. McCaw recognized the necessity of employing blacks at the hospital for the hospital's own survival.

James Brown McCaw,

c. 1850

Courtesy Museum of the Confederacy,

Richmond, Virginia

Hundreds of African Americans, mostly male and enslaved, served as nurses at Chimborazo Hospital. George Cox, and a woman known only as Candis were among the few free blacks that worked there. Their wages were paid directly to them while slave owners received the wages for the work of their slaves. Enslaved African Americans working in Chimborazo had a chance to move from a private to a public work environment where they worked alongside free blacks.

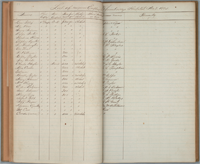

Recorded list of "Negroes Employed in Chimborazo Hospital No. 2, 1864"

Courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Read the Transcript (pdf)

!["…I have at this time only two hundred and fifty-six cooks and nurses [slaves] in my Hospitals, to take care of nearly four thousand sick soldiers...it will be entirely impossible to continue the hospital without them." James Brown McCaw, surgeon-in-charge, Chimborazo Hospital, 1862. I have at this time only two hundred and fifty-six cooks and nurses [slaves] in my Hospitals, to take care of nearly four thousand sick soldiers...it will be entirely impossible to continue the hospital without them. James Brown McCaw, surgeon-in-charge, Chimborazo Hospital, 1862.](images/mccaw.png)

Previous

Previous