Cesarean Section - A Brief History

Part 2

In Western society women for the most part were barred from carrying out cesarean sections until the late nineteenth century, because they were largely denied admission to medical schools. The first recorded successful cesarean in the British Empire, however, was conducted by a woman. In 1826, James Miranda Stuart Barry performed the operation while masquerading as a man and serving as a physician to the British army in South Africa.

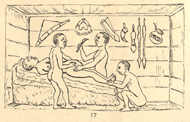

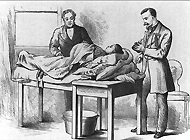

Successful Cesarean section performed by indigenous healers in Kahura, Uganda. As observed by R. W. Felkin in 1879 from his article "Notes on Labour in Central Africa" published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal, volume 20, April 1884, pages 922-930.

While Barry applied Western surgical techniques, nineteenth-century travelers in Africa reported instances of indigenous people successfully carrying out the procedure with their own medical practices. In 1879, for example, one British traveller, R.W. Felkin, witnessed cesarean section performed by Ugandans. The healer used banana wine to semi-intoxicate the woman and to cleanse his hands and her abdomen prior to surgery. He used a midline incision and applied cautery to minimize hemorrhaging. He massaged the uterus to make it contract but did not suture it; the abdominal wound was pinned with iron needles and dressed with a paste prepared from roots. The patient recovered well, and Felkin concluded that this technique was well-developed and had clearly been employed for a long time. Similar reports come from Rwanda, where botanical preparations were also used to anesthetize the patient and promote wound healing.

The Woman's Hospital of the State of New York, 1867.

One of America's first large hospitals for the diseases of women.

While many of the earliest reports of cesarean section issue from remote parts of Europe and the United States and from places far removed from the latest developments in Western medicine, it was only with increased urbanization and the growth of hospitals that the operation began to be performed routinely. Most rural births continued to be attended by midwives in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but in the cities obstetrics -- a hospital-based specialty -- squeezed out midwifery. In urban centers large numbers of uprooted working class women gave birth in hospitals because they could not rely on the support of family and friends, as they could in the countryside. It was in these hospitals, where doctors treated many patients with similar conditions, that new obstetrical and surgical skills began to be developed.

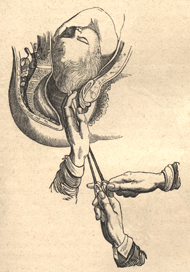

A Cesarean patient prior to dressing the wound. From Edward Siebold, Abbildungen aus dem gesammtgebiete der theoretisch-praktischen geburtshülfe, 1829.

Special hospitals for women sprang up throughout the United States and Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. Reflecting that period's budding medical interest in the sexuality and the diseases of women, these institutions nurtured the emerging specialties and provided new opportunities for medical practitioners, as well as new treatments for patients. Specialties such as neurology and psychiatry centered on mental and nervous disorders and obstetrics and gynecology centered on the functions and disorders of the female reproductive tract.

As a serious abdominal operation, the development of cesarean section both sustained and reflected changes within general surgery. In the early 1800s, when surgery still relied on age-old techniques, its practitioners were dreaded and viewed by the public as little better than barbers, butchers, and tooth pullers. Although many surgeons possessed the anatomical knowledge and the courage to perform serious procedures they had been limited by the patient's pain and the problems of infection. Well into the 1800s surgery continued to be barbarous and the best operators were known for the speed with which they could amputate a limb or suture a wound.

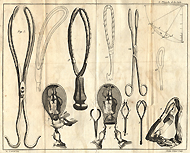

Craniotomy. Perforation of the skull, removal of cranial contents, and extraction of the collapsed skull.

During the nineteenth century, however, surgery was transformed -- both technically and professionally. A new era in surgical practice began in 1846 at Massachusetts General Hospital when dentist William T. G. Morton used diethyl ether while removing a facial tumor. This medical application of anesthesia rapidly spread to Europe. In obstetrics, though, there was opposition to its use based on the biblical injunction that women should sorrow to bring forth children in atonement for Eve's sin. This argument was substantially demolished when the head of the Church of England, Queen Victoria, had chloroform administered for the births of two of her children (Leopold in 1853 and Beatrice in 1857). Subsequently, anesthesia in childbirth became popular among the wealthy and practical in cases of cesarean section.

By the century's close, a wide range of technological innovations had enabled surgeons to revolutionize their practice and to professionalize their position. Anesthetics permitted surgeons to take the time to operate with precision, to cleanse the peritoneal cavity, to record the details of their procedures, and to learn from their experiences. Women were spared the agony of operations and were less susceptible to shock, which had been a leading cause of post-operative mortality and morbidity.

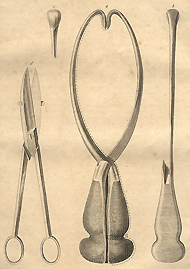

Obstetrical forceps. From André Levret's Observations sur les causes et les accidens de plusieurs accouchemens laborieux, 1750.

As many doctors discovered, anesthesia allowed them to replace craniotomy with cesarean section. Craniotomy had been practiced for hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years. This unhappy procedure involved the destruction (by instruments such as the crotchet) of the fetal skull and the piecemeal extraction of the entire fetus from the vagina. Although this was a gruesome operation, it entailed far lower risk to the mother than attempts to remove the fetus through an abdominal incision.

While obstetrical forceps helped to remove the fetus in some cases, they had limitations. They undoubtedly saved the lives of some babies who would otherwise have suffered craniotomy, but even when the mother's life was saved, she might well suffer severely for the rest of her life from tears in the vaginal wall and perineum. The low forceps that are still commonly used today could cause vaginal tears, but they were less likely to do so than the high forceps that in the nineteenth century were too frequently employed. Inserted deep into the pelvis in cases of protracted labor, these instruments were associated with high levels of fetal damage, infection, and serious lacerations to the woman. Dangerous as it was, cesarean section may have seemed preferable in some instances when the fetus was trapped high in the pelvis. Where severe pelvic distortion or contraction existed, neither craniotomy nor obstetrical forceps were of any avail, and then cesarean section was probably the only hope.

Abdominal surgery to remove diseased ovarian tissue (ovariotomy). Surgeon and anesthesiologist in street clothes. From Thomas Spencer Wells, Diseases of the Ovaries, 1872.

While doctors and patients alike were encouraged by anesthesia to resort to cesarean section rather than craniotomy, mortality rates for the operation remained high, with the infections septicemia and peritonitis accounting for a large percentage of post-operative deaths. Prior to the establishment of the germ theory of disease and the birth of modern bacteriology in the second half of the nineteenth century, surgeons wore their street clothes to operate and washed their hands infrequently while passing from one patient to another. In the mid-1860s, the British surgeon Joseph Lister introduced an antiseptic method using carbolic acid, and many operators adopted some part of his antisepsis. Others, however, were concerned about its corrosiveness and experimented with various aseptic measures that emphasized cleanliness. By the end of the century antisepsis and asepsis gradually were making inroads into the problems of surgical infections.

Unfortunately, surgical techniques of that day also contributed to the appallingly high maternal mortality rates. According to one estimate not a single woman survived cesarean section in Paris between 1787 and 1876. Surgeons were afraid to suture the uterine incision because they thought internal stitches, which could not be removed, might set up infections and cause uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies. They believed the muscles of the uterus would contract and close spontaneously. Such was not the case. As a result some women died of blood loss -- more from infection.

Last Reviewed: March 6, 2024