United States 19th-Century Doctors'

Thoughts about Native American Medicine

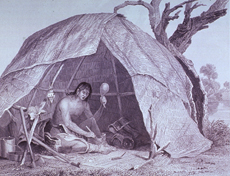

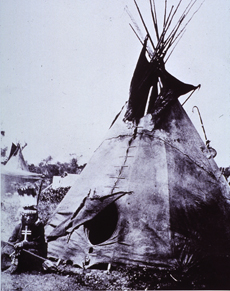

Euroamerican doctors of the 19th-century almost invariably considered Native American medical technique to be inferior to their own practices: Examples displayed here are representative. At the same time, however, "Indian cures" were quite popular and very marketable among members of the general public. Prefaced to some of these "Indian cures" might be the name of a doctor, as in the patent medicine card here.

Regardless of the general feeling of superiority that reflects a high degree of cultural imperialism, Euroamerican doctors were intrigued by Native American medicine. They wrote numerous articles that were published in medical journals, like those displayed here.

However intrigued, Euroamerican doctors generally did not espouse the use of Native American medicine and would more often judge these techniques as uncivilized. This attitude was shared by the Office of Indian Affairs toward the close of the 19th- and opening of the 20th-century. It would shape government health care policy and ultimately lead to the education of Native Americans in white-dominated medical schools (See exhibit cases 8A, 8B and 9).

Exhibit Case 2

"We have no discoveries in the materia medica to hope for from the Indians in North-America. It would be a reproach to our schools of physic, if modern physicians were not more successful than the Indians, even in the treatment of their own diseases." - Benjamin Rush

Source: Benjamin Rush, An Inquiry Into the Natural History of Medicine Among the Indians, 1789 (originally read in 1774 before the American Philosophical Society) [book was displayed in exhibit case].

"MAKING MEDICINE MEN. At a certain period of each year, all young braves, who are ambitious to become great or medicine men, assemble and go through the horrible ordeal which is to render them immortal. A minute description of this terrible course of training and final graduation would be as interesting as astonishing; but time will not permit full details, and I shall content myself with as concise a statement as will be compatible with perspicuity. After three or four days of fasting, praying and privation, and after having witnessed all the mysterious movements of those advanced in the science, the ambitious young men present themselves for the last and most trying test of greatness. They enter the great medicine lodge, where the ceremonies have been celebrated for four days, and place themselves in a reclining position, when immediately the executioners commence their work, by pinching up an inch or two of the integument and pectoralis major muscle of each side, and thrusting a ragged knife through the flesh beneath the fingers; after which skewers are passed through the wounds thus made. A similar operation is performed in several places over the trapezius muscle, and often on the front part of the thigh, the leg or the forearm. To these skewers or sticks, passed beneath the integument and through the muscles, cords are attached, by means of which the candidates are raised clear of the ground, and left dangling until apparently dead, having fainted repeatedly. They are then lowered down and left without the slightest aid or comfort until reaction takes place, when heavy weights, such as buffalo heads are attached to the skewers and kept dragging on the ground or suspended in the air as the poor sufferers are hurried from place to place, until they are torn loose by their own weight, or by being caught in some way as they madly rush over the plains around the encampment. The Sioux have even a more refined process of testing or torturing the ambitious than that just described as common to most North American Indians. They pass skewers through the pectoral muscles as above mentioned, and then fasten their victims to a strong sapling just stiff enough to raise them on tiptoe, in which position, with the head thrown back, they are compelled to gaze at the shining sun from its rising to its setting; and if one faints or falls whilst undergoing the trial before the sun has disappeared, he is forever disgraced as a man without medicine."

Source: Thomas Kennard, "Medicine Among the Indians," St. Louis Medical and Surgical Journal, Vol. 16, 1858, pp. 392-3.

"The State of medical knowledge among these Indians (Onondagas) may be briefly told. Their knowledge of remedies and of diseases is so vague and limited that it is a marvel why any sane quack should think to add to his popularity by styling himself an Indian Doctor, or should hope to increase the sale of his nostrums, by giving them the christian name of some unpronounceable Indian tribe. A few roots, leaves, and barks of recognized medicinal powers, such as black cohosh, mandrake, apocynum, and spigelia, and many more of no potency for good or evil, as witch-hazel, wild grape-vine roots, angelica, fire-weed, together with Epsom salts and castor oil, make up the most of their Materia Medica. They have here a chief who glories also in the title of Indian Doctor, who practises a little in the tribe, and among some of the ignorant and credulous whites in the surrounding section. He is very limited in his remedies, but makes up the lack in boasts and pretensions, which prove him a counterpart -- perhaps a near relative -- of Longfellow's Iago.

There are a few squaws who dispense mysteriously manipulated compounds of roots, leaves, and barks, infused in large quantities of warm water, given warm, or added to rum or whiskey, and given for months to chronic invalids; but none of these ever extract teeth, bleed, cup, adjust broken or dislocated bones, or open swellings--for all surgery or operative midwifery they depend on 'white doctors' or nature, and so destitute were they of the means of paying for medical and surgical attendance, even where they might have disposition to pay, that nature had been trusted to in many cases where timely aid might have saved life, or preserved limbs from terrible distortion."

Source: Jonathan Kneeland, "On Some Causes Tending to Promote the Extinction of the Aborigines of America," Transactions of the American Medical Association, Vol. 15, 1864, p. 257.

"The American Indian has been, and is given credit for a wonderful knowledge of medicine. Compounds purporting to have originated among some of the numerous tribes, have attributed to them wonderful healing powers, and are readily sold to persons at good prices; who would not be guilty of paying a like amount to their local physician, for real services rendered in the past. They will pay the Indian Doctor, or the man who sells Indian cures, a good round sum for the article vended, and never question but that they have value received. I had opportunities for witnessing the preparation of their wonderful remedies, and also their application of these same remedies at home, in cases of sickness, and the wonderful cures produced at the fountain head, as it were. My point of observation was at Fort Berthold, North Dakota, among the Arickarees, Gros Ventres and Mandans.

In the Fall of the year, at some certain quarter of the moon, our Indian medicine men were accustomed to assemble in solemn conclave on a certain knoll. In the centre of the circle were deposited various plants and some branches of trees. What the specific performance was that brought out the medicinal virtues of these plants, I never took time to find out; having my hands full, supplying sick Indians with white man's medicine. However, after a certain amount of gesticulating, smoking the medicine pipe and blowing the smoke towards the different points of the compass, the leaves, being all this time exposed to the hot sun and dry winds, having become dry, were rubbed between the hands and broken up, placed in little bags, and divided among the medicine makers. I presume the leaves had become imbued with the virtues of the Great Spirit during the performance. These medicine men were now supplied with medicine possessing virtues to heal all the ills that flesh is heir to. And it didn't cost them like it does the modern physician, who has to depend on the manufacturing druggist for his supplies. Neither does your Indian medicine man have to label his medicines. It seems entirely immaterial from which packet he draws his supplies for the treatment of any given case. The effect of one is just as good as another."

Source: J. L. Neave, "An Agency Doctor's Experiences Among Frontier Indians," Cincinnati Medical Journal, Vol. 9, 1894, pp. 875-6.

Dr. Kilmer's Indian Cough Cure Consumption Oil.

19th-century patent medicine card purporting Kilmer's oil to be an authentic Native American remedy.

Last Reviewed: March 5, 2024