Ever since the invention of moveable type in the mid-1400s, the public’s appetite for tales of shocking murders—“true crime”—has been an enduring aspect of the market for printed material. The murder pamphlets in the National Library of Medicine collections were mostly acquired in the mid- and late 19th century. Some deal with cases catalogued under the subject category of “medical jurisprudence” or “forensic medicine”. Others deal with notorious cases in which doctors were accused of, or were victims of, heinous crimes. Still others have no medical connection whatsoever, beyond dealing with death.

True Account

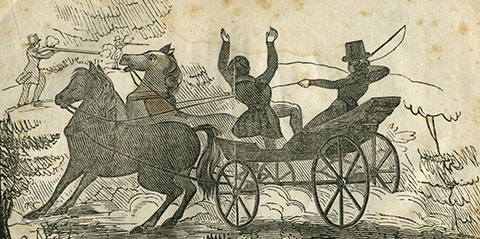

For more than five centuries, murder pamphlets have been hawked on street corners, town squares, taverns, coffeehouses, newsstands, and book shops. Typically, a local printer would put together a pamphlet that claimed to be a true account of a murder, consisting of a narrative, trial transcript, and/or written confession of the murderer before his or her execution.

Trial of Professor John W. Webster

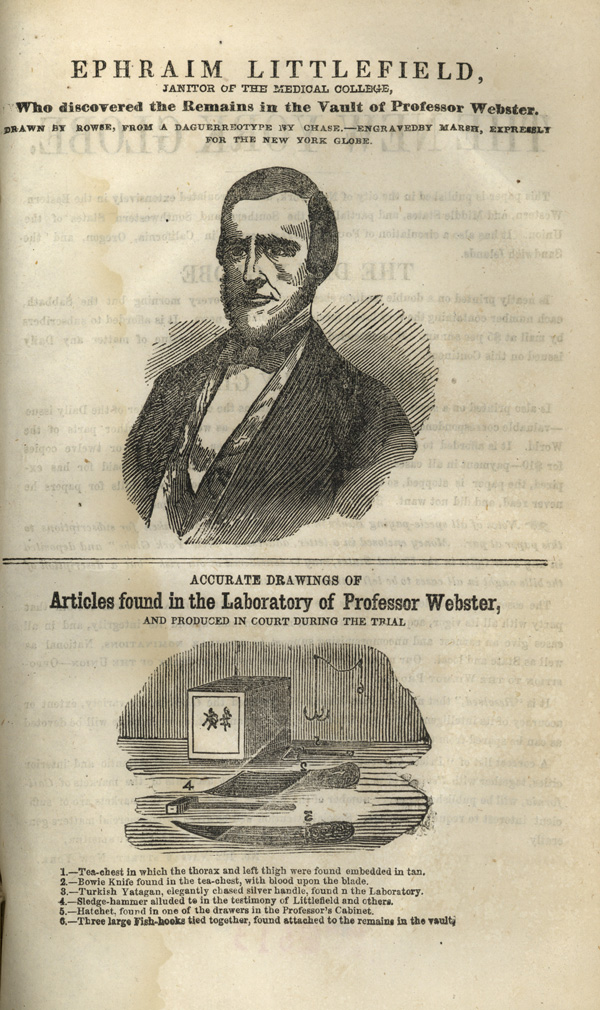

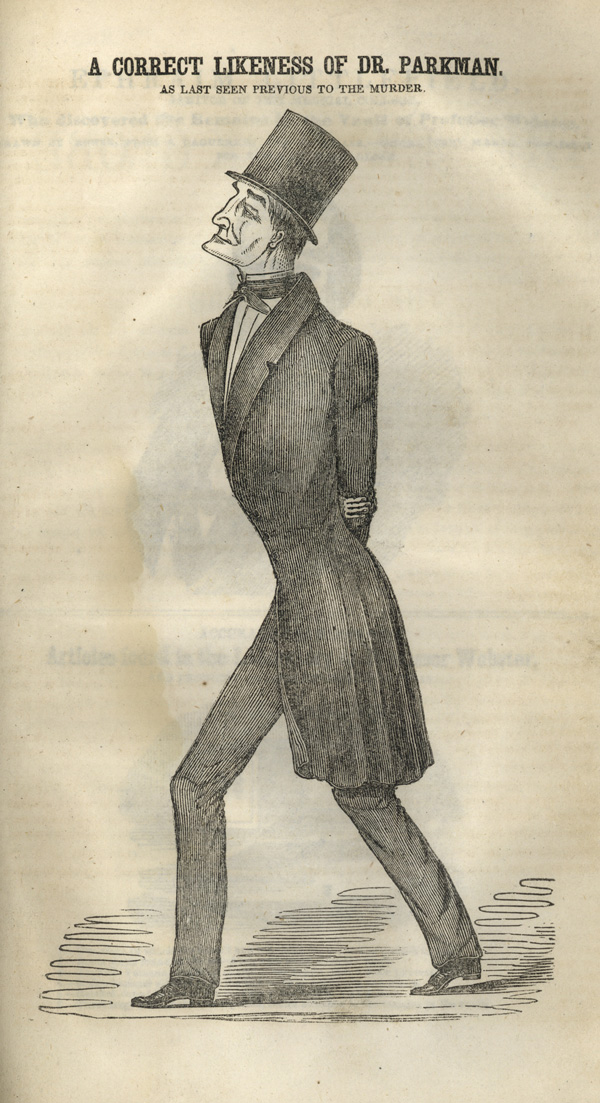

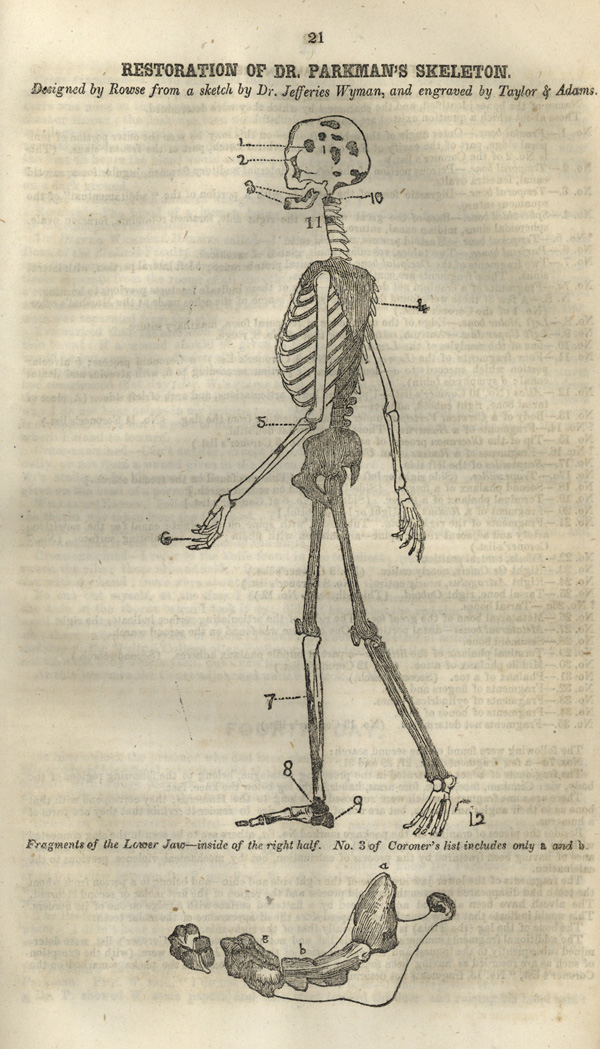

The 1849 murder of the wealthy and prominent Dr. George Parkman was the subject of many pamphlets. Dr. John Webster, a chemistry professor at Harvard Medical College, borrowed money from Parkman and couldn’t pay it back. Parkman went missing and was last seen entering the College for an appointment with Webster. The chief witness in the case, Ephraim Littlefield, a janitor, lived next to Webster’s laboratory and noticed that Webster was making numerous trips to the furnace of the dissecting laboratory. Littlefield began to chisel away at the wall near Webster’s lab and tunneled into a privy, which emptied into a pit. After a few days, he broke through a wall, and found a dismembered thigh and the lower part of a leg. Further investigation turned up a bone fragment in the dissecting lab furnace, as well as a jawbone with teeth, a button, and coins. A chest was later found which contained a thigh stuffed in a torso that was missing a heart and other organs. Parkman’s brother-in-law identified the body by its extreme hairiness and at trial, a dentist identified the fake teeth he had made for Parkman. Medical experts laid out the body parts and estimated the height to be 5’10”—Parkman’s height. Webster was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

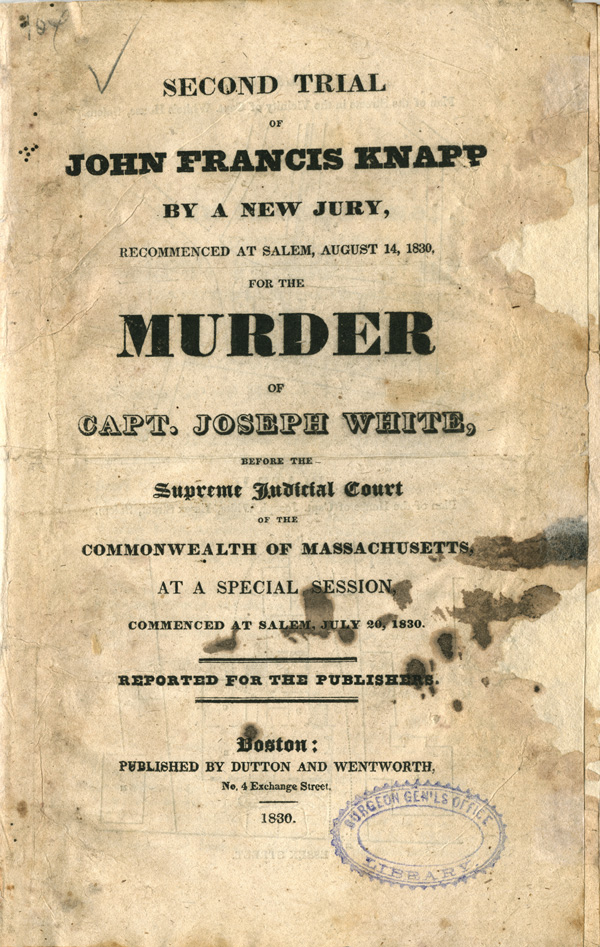

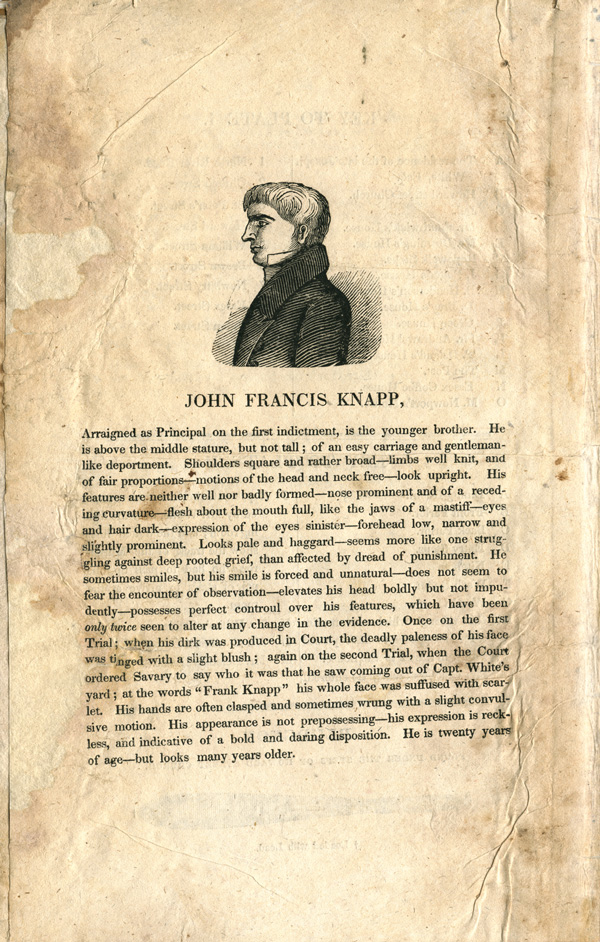

Trial of John Francis Knapp

John Francis and Joseph Knapp hired Richard Crowninshield to murder their uncle Joseph White, a Salem, Massachusetts sea captain, in order to inherit some of his wealth. On an April night in 1830, Crowninshield entered White’s home and stabbed him to death, while the brothers remained outside, a few hundred yards away. A man arrested for pickpocketing stated that Crowninshield had confessed to him the murder of Captain White. Crowninshield denied any connection to the Knapps. However, another man, John Palmer, knew of the murder plot and sent the Knapps a blackmail note, which came to the attention of the authorities. Both brothers were arrested for murder, but before Crowninshield could testify against them, he hung himself in his cell. Under Massachusetts common law, accessories to a crime could not be convicted unless the murderer testified to their relation or if the accessories were immediately present at the murder. However, renowned lawyer Daniel Webster argued that the Knapps were near enough to the crime to have aided the murderer. The brothers were found guilty and hanged.

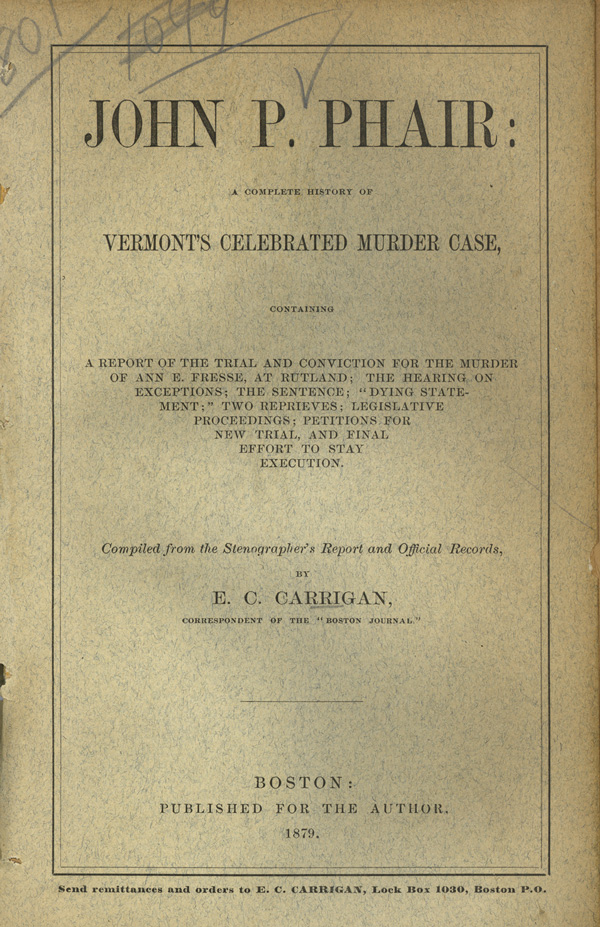

John P. Phair: A Complete History of Vermont's Celebrated Murder Case

In June 1874, firemen putting out a blaze at a house in Rutland, Vermont discovered the body of Ann Freeze, a 27-year-old sex worker. Freeze’s throat had been cut, her body had several stab wounds, and her jewelry was missing. Suspicion fell on John P. Phair, a handsome young mechanic with a criminal record, who had been Freeze’s lover. Phair went into hiding but was discovered attempting to pawn goods stolen from Freeze. He was arrested for murder and found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. New evidence came to light, and the Governor granted Phair several reprieves. He was finally hanged in 1879, after almost five years on death row.

Varieties

Some murder pamphlets were written in a sober tone and set in a sober typeface. Others were sensationalist, with extravagant language and eye-catching headlines. Some provided nothing more than a bare trial transcript. Others featured novelistic descriptions purporting to tell the details of the case, with portraits of victims and suspects, and lurid engravings of the crime. Some murder pamphlets took on some of the characteristics of the murder mystery genre and presented the case as a puzzle. Others confidently asserted from the outset the identity of victim and murderer. Very often, several different pamphlets would comment on a single case, either independently or disputing each other. Pamphlets varied in length, from eight pages to over two hundred, were printed on cheap paper, and usually sold for a low price.

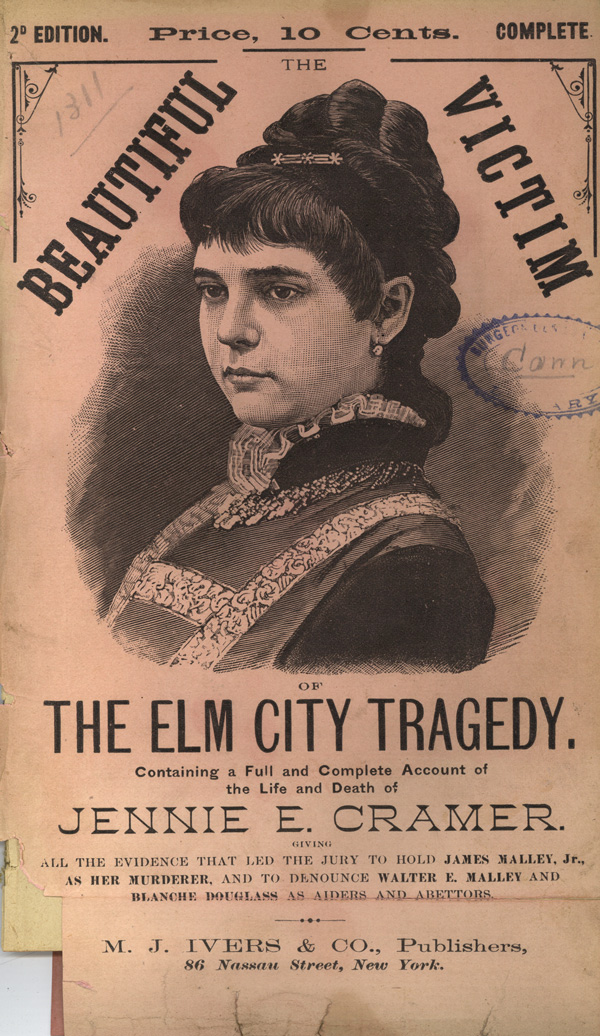

The Beautiful Victim of the Elm City Tragedy

In August 1881, the body of Jennie Cramer, a 20-year-old society girl, was found by a fisherman on a Connecticut shore. It was initially believed she had committed suicide by drowning, but an autopsy showed that there was no water in her lungs, that she had been raped and poisoned with laudanum. Prior to her death she had been seen with James Malley, his cousin Walter Malley, and Walter’s friend Blanche Douglas, a sex worker. The Malleys came from a wealthy family that owned a New Haven department store. On the Wednesday prior to the discovery of her body, Cramer had gone to the Malley mansion with Douglas and spent the night. Douglas and the Malleys claimed that they did not see her after that, but witnesses testified that Cramer had been with them prior to her murder. After a trial of three months, the accused were acquitted. There was no definite proof to tie the accused to the murder, but many townspeople suspected that the wealthy Malleys had paid off the jury to acquit.

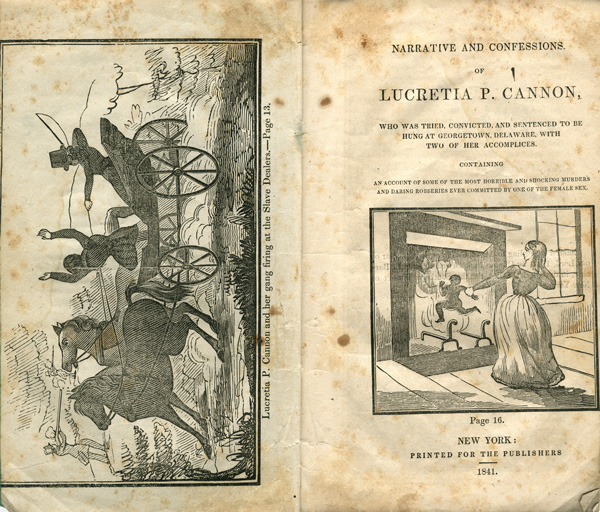

Narratives & Confessions of Lucretia P. Cannon

The Murders of Lucretia Cannon is a sensationalist and unreliable account. Cannon’s first name was Patty, but the press nicknamed her Lucretia after Lucretia Borgia, the Renaissance aristocrat who murdered her victims with poison. At 16, “Lucretia” married Alonzo Cannon, who died suspiciously of “failing health” three years after entering into the marriage. Widowed, she set up a tavern in Maryland, and headed up a gang which captured free blacks and fugitive slaves and sold them into slavery. She was alleged to have beaten a crying infant and then burned it alive; murdered tavern patrons for their money (one man was stabbed and stuffed into a trunk which her accomplices disposed of); killed a slaver by crushing his head in order to steal his two slaves. Cannon's career came to an end when neighbors used a search warrant to enter her house and discovered twenty-one black captives and many skeletons in the backyard. At trial, Cannon was sentenced to death. To avoid hanging, she took poison which killed her, but first led her to break down and confess to killing eleven people, acting as an accessory to twelve other deaths, poisoning her husband, and killing her three-day-old child.

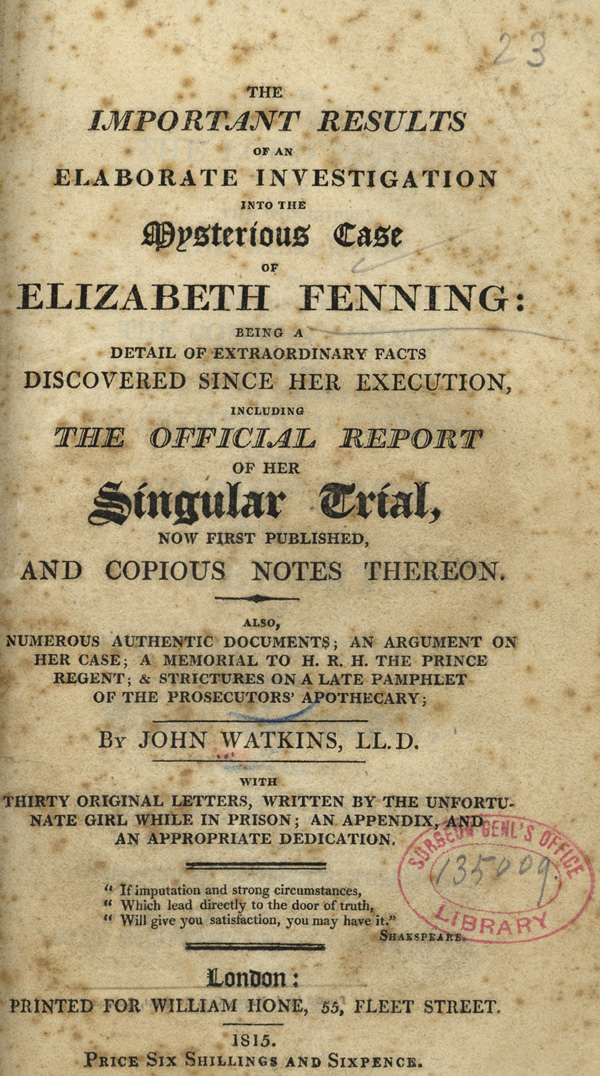

The Mysterious Case of Elizabeth Fenning

In London in 1815, Elizabeth Fenning, a 20-year-old maid, was arrested for intent to commit murder. Charlotte Turner, her mistress, had discovered Fenning in a state of partial undress in the apprentices’ room and reprimanded her; Fenning resented the reprimand. Sometime after that, Fenning made strange-looking dumplings for the Turner family and apprentices. All who ate them became ill, including Fenning. Upon examination, it was found that the dumplings contained arsenic. At trial, Fenning was found guilty and sentenced to die, despite her assertions of innocence. Many Londoners considered the verdict to be unjust. After the execution, some 10,000 people escorted the body to the church grounds.

The Suspect

Murder pamphlets often did not list an author. But sometimes the suspect would contribute to the writing and publication of the murder pamphlet, as a forum to proclaim his or her innocence, or to justify or explain why the act had been committed.

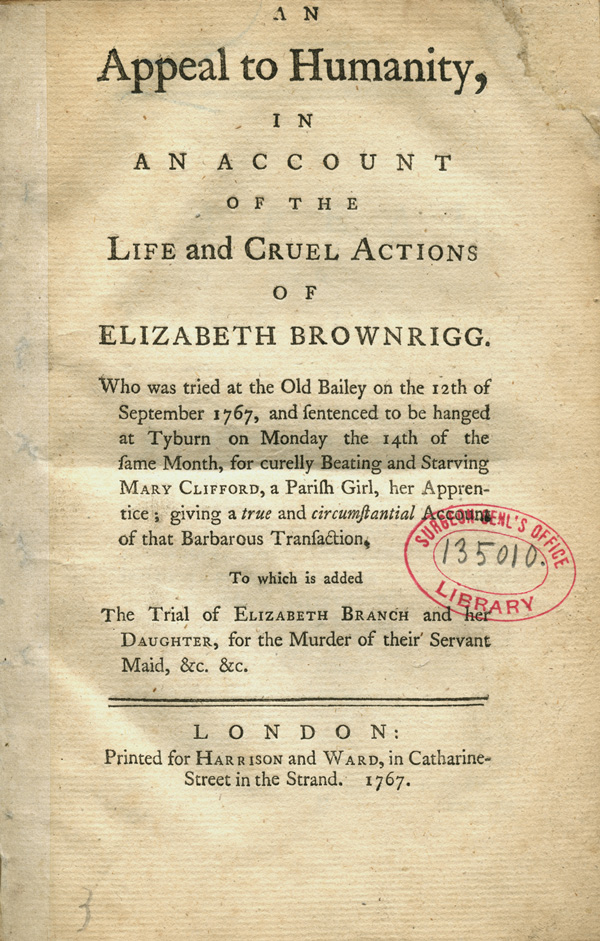

The Life & Cruel Actions of Elizabeth Brownrigg

In 1765, London midwife Elizabeth Brownrigg took in two apprentices. The girls were severely abused by Brownrigg and her husband, and one of them, Mary Clifford, was found locked in a cupboard with sores all over her body, lash marks around her neck, and her mouth so swollen she was unable to speak. Clifford was taken to a hospital where she died. At trial, Brownrigg was identified as the principal culprit, found guilty of murder and sentenced to be hanged. She confessed her guilt on the scaffold. After the hanging, her body was dissected and her skeleton was put on display in Surgeon’s Hall.

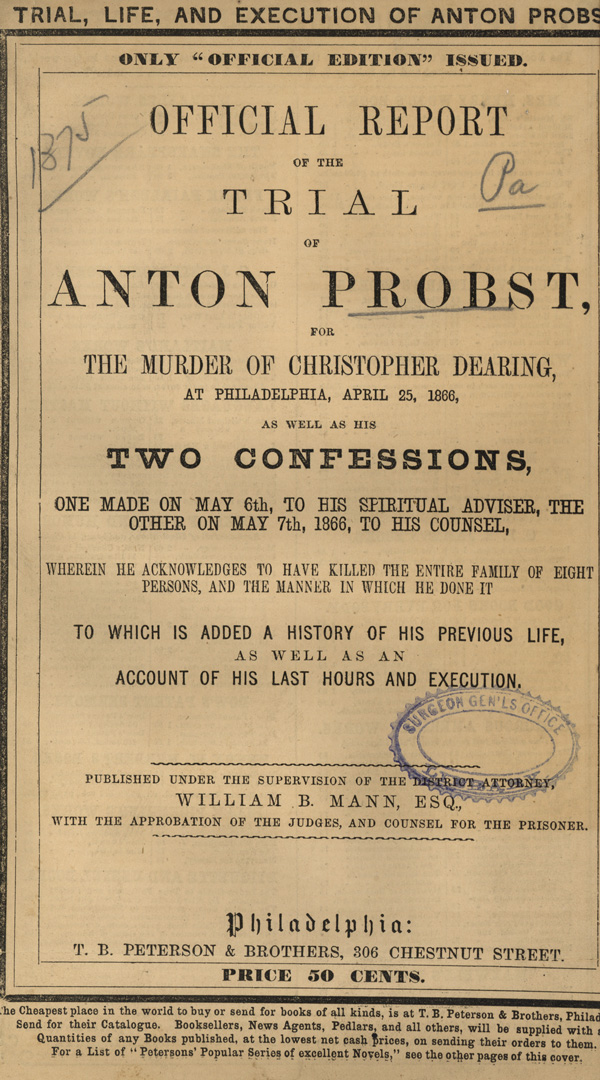

Trial, Life & Execution of Anton Probst

In 1866, at a farm near Philadelphia, a neighbor discovered the bodies of Christopher Dearing, his wife, four children, a family friend, and an employee, hidden under piles of hay with slit throats and crushed skulls; the farm animals were starving and the house had been ransacked. A few days later, police found in Anton Probst's possession a carpetbag containing the Dearings’ belongings. Probst, an impoverished German immigrant who had worked as a handyman for the Dearings, was charged with murder. At trial, the medical experts noted that the throats were most likely cut by an axe, and that only a very strong man could have hauled the bodies and covered them over with 500 pounds of hay. The jury found Probst guilty; he was sentenced to be hanged. After his execution, doctors performed galvanic experiments on his corpse and dissected it. His skeleton was later put on display in a medical school.

The Trial & Execution of Dr. John W. Hughes

In Cleveland, in 1864, John Hughes, a reckless and drunken 31-year-old Army surgeon, seduced 17-year-old Tamzen Parsons. After he showed her a forged divorce decree, she eloped with him to Pittsburgh. When her parents discovered her missing, they called the police who arrested Hughes in the couple’s bridal suite. Convicted on charges of bigamy, Hughes served five months in jail. Upon his release, he stalked Parsons. At the front gate of her house, Hughes threatened to kill her if she did not marry him. When she spurned his advances, he shot her twice in the back of the neck, instantly killing her. At trial Hughes was found guilty of murder and sentenced to be hanged.

The Witnesses

Sometimes a doctor or surgeon who served as expert witness in the case would write the pamphlet to consider the “medico-legal” and scientific aspects. Such pamphlets were usually addressed to medical colleagues and lawyers, but also attracted a collateral audience among the wider public.

The Maria Hendrickson Murder

In 1853, Maria Hendrickson was found dead. An autopsy revealed tincture of aconite in her system. Her husband John Hendrickson was charged with her murder. At trial it came out that in 1851 Hendrickson had assaulted a young woman and, through his philandering, had contracted a venereal disease which he passed onto his wife. Witnesses testified that, on the week of his wife’s death, Hendrickson went to a pharmacy and inquired about prussic acid, a fatal poison. The case focused on forensic medical issues. Both the prosecution and defense called on doctors to testify about the state of the body and the properties of aconite, an extract which removes water and causes dehydration. The doctors fed tincture of aconite to cats, and observed that they suffered convulsions and vomiting. In dissection, the cats were seen to have shriveled organs. Some witnesses testified that Maria Hendrickson suffered from severe vomiting prior to death and in the autopsy her stomach, gall bladder and intestines had a shriveled appearance. The defense countered that Maria did not vomit and her bed sheets were not stained. The jury found Hendrickson guilty of murder by poison, and he was sentenced to death by hanging.

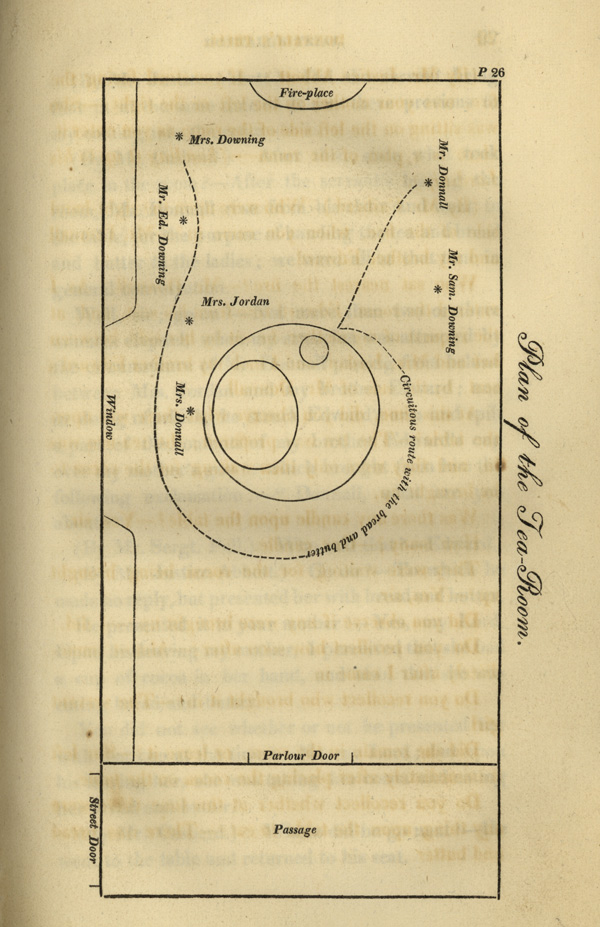

Trial of Robert Donnall

In 1816 Robert Donnall was charged with the murder of Elizabeth Downing. He was deeply in debt, and Mrs. Downing, his mother-in-law, had money which he stood to inherit. At trial, it was alleged that Downing had fallen ill after a poisoning incident, and Donnall, being a doctor, attended to her. A second incident led to her death. Donnall tried to have the body immediately buried. But instead the body was autopsied and Downing’s stomach-lining was found to be nearly dissolved by a corrosive agent. The autopsyists saved of the stomach contents in a bowl, which Donnall threw out. But another set of contents was saved and traces of arsenic found. Medical experts for the defense claimed that Downing could have died of cholera morbus or another gastrointestinal disease. The prosecution argued that such a death would take weeks, not hours. With the conflicting evidence, Robert Donnall was acquitted.

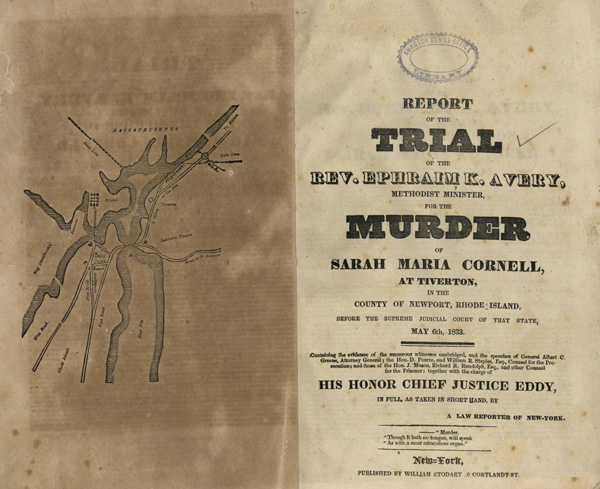

The Trial of Ephram Avery

In 1832 Ephraim Avery, a Methodist minister, was charged with the murder of Sarah Maria Cornell. Cornell, a young factory worker, was found hung up on a stake, beaten and choked. At trial, the prosecution brought forth letters written by Cornell, warning that if she went missing to inquire of Avery; other letters discussed her fear of being pregnant. Doctors and the women who laid out the body noted that Cornell’s lungs were filled with blood, and her knees had several abrasions. A fetus was found in the body, which, together with damage to the uterus, indicated an attempted abortion. Cornell had been a member of Avery’s church until she was expelled for allegedly lying and behaving promiscuously. The defense claimed that she wanted to punish him, and on several occasions had threatened to commit suicide. Medical witnesses for the defense argued that the bruises found near her groin and abdomen commonly occurred during pregnancy and that the eight-inch fetus was in the fifth month, so that the child could not have been Avery’s. Avery was acquitted, but the verdict was unpopular: a mob burned him in effigy and he was forced to move from Rhode Island to Ohio.

Relevance

Today, murder pamphlets are a rich source for historians of medicine and crime novelists, but also cultural historians, who mine them for material to illuminate the history of class, gender, the law, science, the city, religion and other topics.

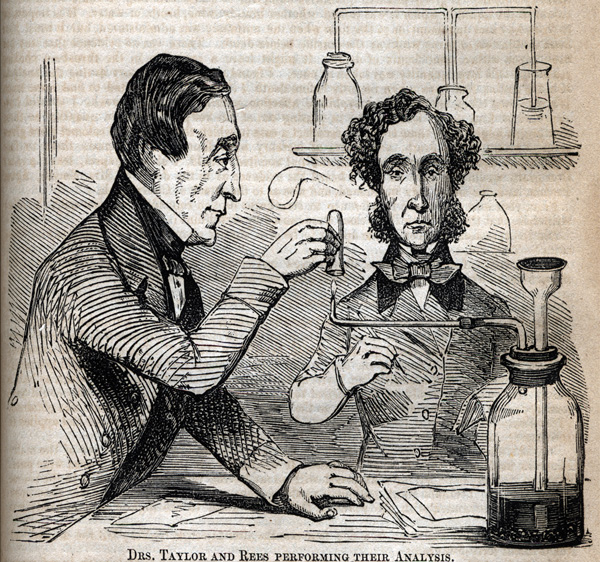

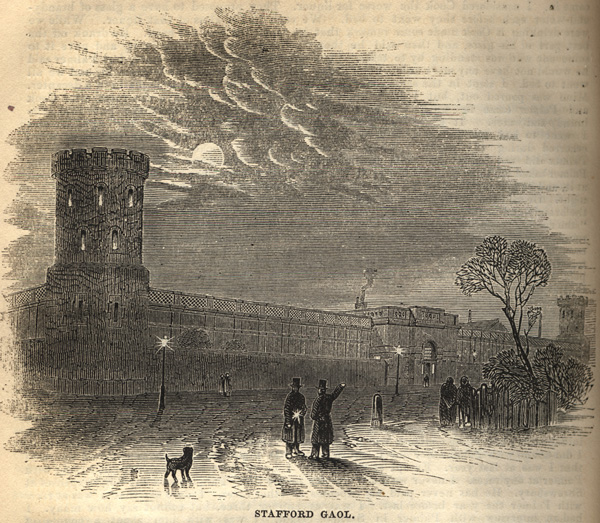

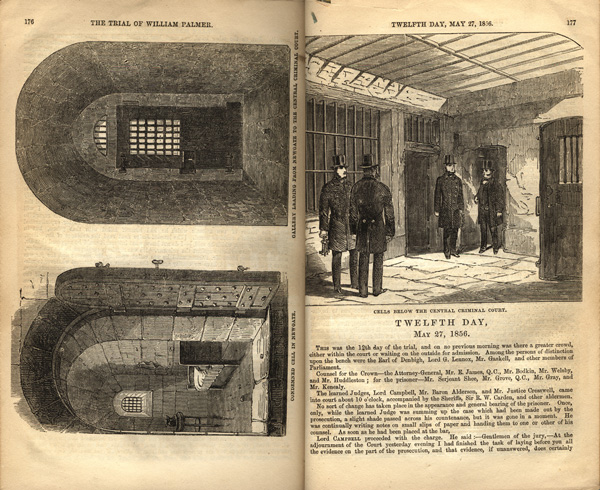

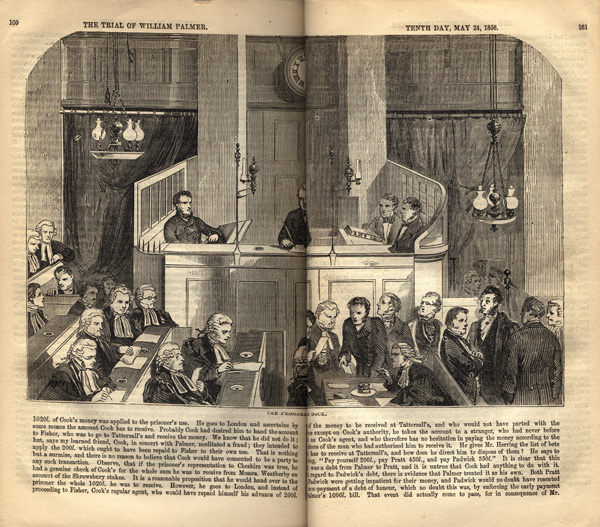

William Palmer

Dr. William Palmer of Staffordshire, England, was a womanizer and gambler. He was tried for the death of his gambling companion John Parsons Cook, but after his arrest, it came out that that Palmer had likely committed many other murders. His mother-in-law died a suspicious death, as did several other people who had loaned money to Palmer. In 1854 his wife Annie fell ill and died, supposedly of cholera; a few months earlier, Palmer had taken out an insurance policy on her life. A maid to the family gave birth to Palmer’s illegitimate son nine months after Annie’s death; the baby died four days later. Palmer then took out a life insurance policy on his brother Walter; Walter died shortly after, but the insurance company refused to pay. By then Palmer was being blackmailed by a former lover and in grave financial difficulty. His friend Cook, who had recently won money at the track, was suddenly stricken with a terrible illness after dining with Palmer. While Palmer was tending to him as a physician, he went to London with Cook’s betting books and claimed his money. Cook died shortly thereafter. His stepfather suspected foul play and insisted on an autopsy. According to the medical experts, the cause of death was strychnine poisoning, but much to the embarrassment of the experts, no traces could be found in the body. Palmer was nevertheless found guilty and hanged, before a crowd of 30,000.

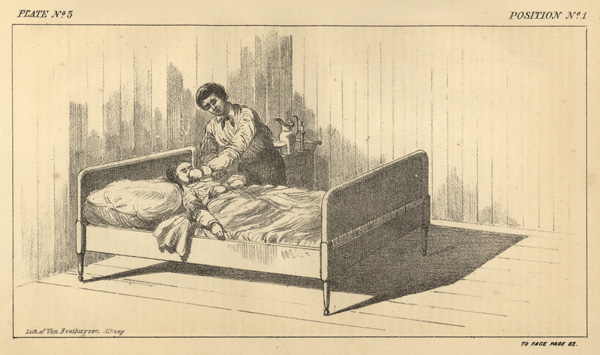

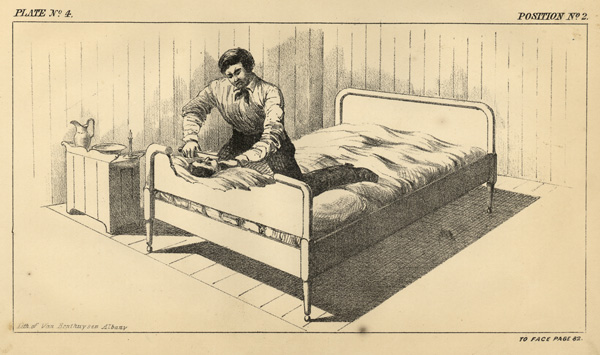

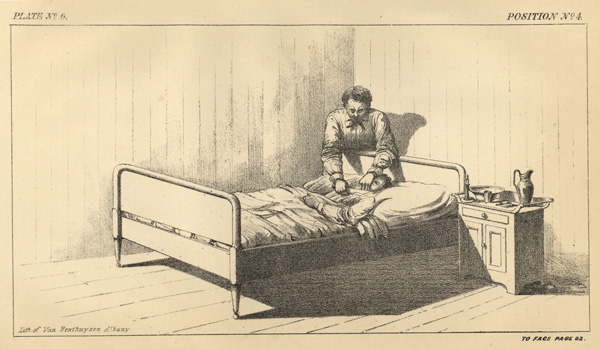

The People Agt. Rev. Henry Budge

In December 1859 in a small town in upstate New York, Priscilla Budge, a 40-year-old housewife, was found dead with her throat slit and a razor near her hand. The death was initially ruled a suicide, but after a postmortem, her husband, Reverend Henry Budge, was charged with murder. At trial, the prosecution and the defense relied heavily on forensic evidence. In this pamphlet, Dr. John Swinburne, reviews the evidence and concludes that Mrs. Budge was murdered. The pamphlet cites the opinions of eminent medical men who were sent copies of Swinburne’s draft report and agreed with his assessment. The appendix discusses fifteen cases of suicide by slitting of the throat and the conditions in which the persons were found. Swinburne notes the amount of blood lost, the bloody appearance of the razors, the depth of the cuts (not as severe as those on Mrs. Budge’s body), and the distorted facial postures (Mrs. Budge’s face was peaceful). The pamphlet's illustrations present different murder scenarios. At trial, the defense argued that Mrs. Budge was insane, murderous and suicidal. With only circumstantial evidence, the jury acquitted Rev. Budge of murder because there was no direct proof.

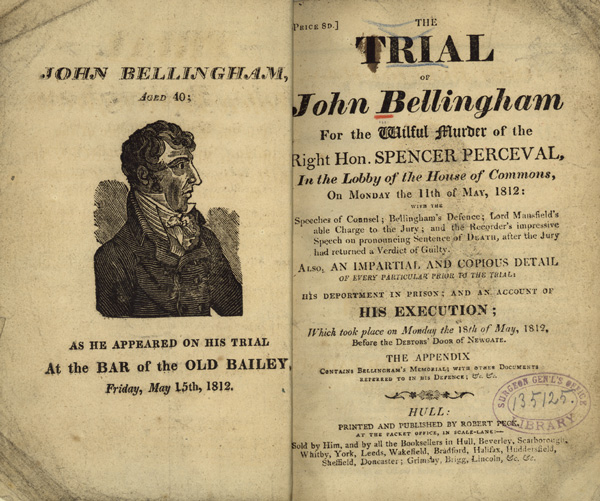

The Trial of John Bellingham

On May 11, 1812, in the British House of Commons, John Bellingham shot and killed Prime Minister Spencer Perceval. At trial, Bellingham did not deny his guilt, but argued that extenuating circumstances, his failed business dealings and imprisonment in Russia and the British government’s refusal to grant him compensation, had driven him to murder Perceval. The defense claimed that Bellingham acted out of insanity, but the insanity plea was denied. Bellingham was found guilty and executed.

About Most Horrible & Shocking Murders

The content of this website is drawn from a display held in the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine, March 6 through June 15, 2008.

The show was curated by Michael Sappol, PhD who was then a Historian at NLM.

You can view the original website created to accompany the display, including the full credits for the project, archived in the NLM Institutional Archives web collection.

This site was designed by Astriata, LLC.

![On the top half of the page is a head and shoulders right profile portrait engraving of John Hendrickson, Jr. with left hand on chin]. On the bottom half of the page is a half-length, right pose, full face engraving of Maria Hendrickson, wife of the prisoner, with her right arm resting on table.](images/hendrickson-3_28410850R.jpg)

Bibliography

Bibliography

Visible Proofs

Visible Proofs

Forensics on Circulating Now

Forensics on Circulating Now