As the owner of Mount Vernon, George Washington was responsible for the health of everyone on the plantation, including his enslaved workers. They numbered over 300 people at the end of his life.

Washington expressed concern that the slaves be given “every necessary care and attention” when unwell and complained that many overseers neglected the slaves when they were too ill to work, “instead of comforting and nursing them when they lye on a sick bed.”

“Disorders…are easier prevented than cured…”

Above quote from a letter from George Washington to Richard Varick, September 26, 1785

Washington the Planter, Louis Conrad Rosenberg, 1933

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

George Washington’s list of slaves at Mount Vernon, 1799

Courtesy Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Washington documented both his own slaves, and the “dower slaves” who belonged to the estate of Mrs. Washington’s first husband. Basic information was recorded for each person, including medical conditions, such as dwarfism, lameness, and senility.

Portrait of Doctor James Craik, a Scottish immigrant who served in the army with Washington and became both the Washingtons’ family doctor and the regular physician for Mount Vernon’s enslaved community

Courtesy Alexandria—Washington Lodge No. 22, A.F. & A.M., Alexandria, Virginia

Photography by Arthur W. Pierson

Trained at the medical school at the University of Edinburgh, Dr. Craik treated both whites and blacks at Mount Vernon. Between August 1797 and June 1799, he bled 39 patients, extracted six teeth, and prescribed a variety of medications. He also made use of home remedies including herbal teas, rice water for dysentery, and honey and vinegar for sore throats.

Dental scaler set, 1795–1850; said to have been used to clean the teeth of slaves at Mount Vernon

Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

Washington routinely visited sick slaves and oversaw numerous health efforts, including dental care.

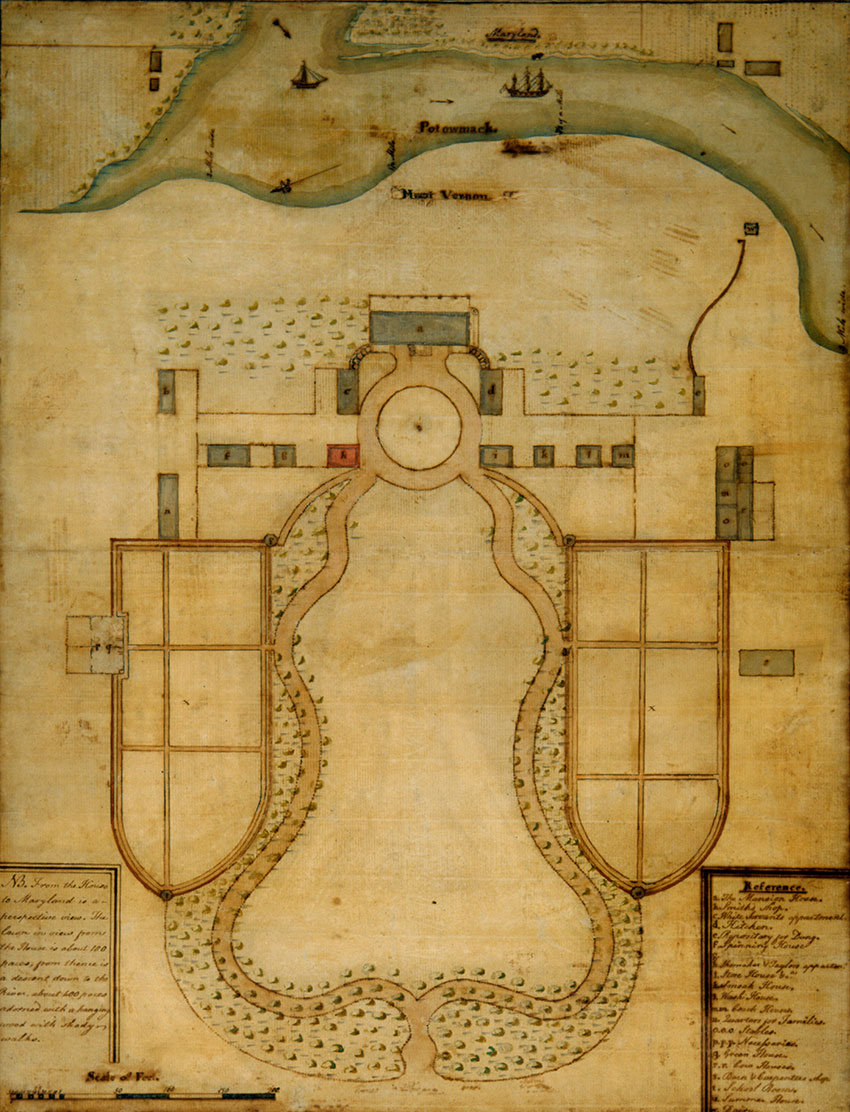

Plan of Mount Vernon by Samuel Vaughan, 1787

Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

The highlighted building was initially constructed in the 1770s as a hospital for sick slaves.

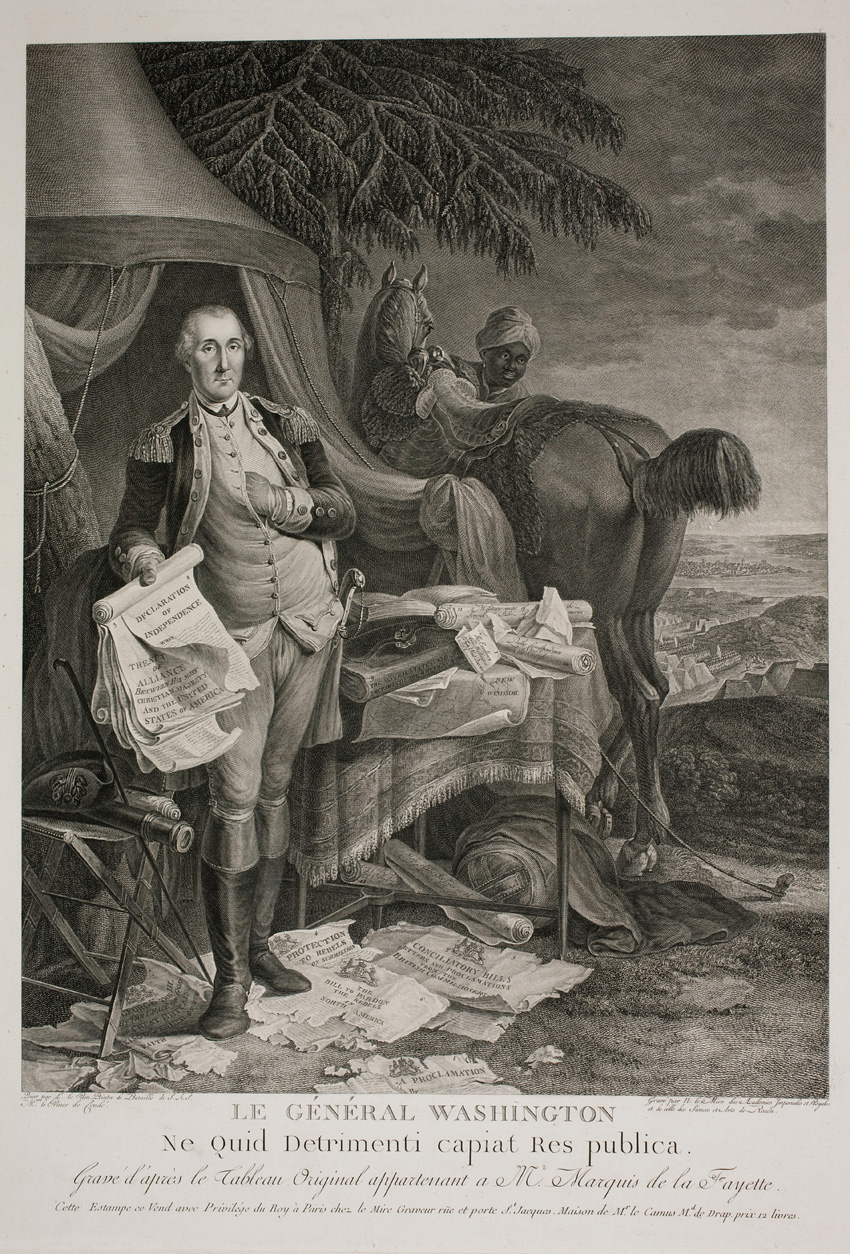

Le General Washington, Noël Le Mire, Jean Baptiste Le Paon, Charles Willson Peale, 1780; Washington’s enslaved valet, William Lee, is shown to the right

Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

George Washington’s long-time valet, William Lee, suffered two serious accidents in the 1780s which dislocated the knee caps of both legs, resulting in permanent disability. Because he could no longer perform his regular duties, Lee became the plantation’s shoemaker instead.

The Washington Family/La Famille de Washington, Edward Savage, David Elkin, 1798

Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

When cases were beyond the abilities of local physicians, help was sought elsewhere. After his valet, Christopher Sheels (possibly shown on the right in this engraving), was bitten by a family dog in 1797, Washington sent the young man to William Stoy in Pennsylvania, who specialized in rabies. Christopher survived.